Crossing the genres; shaking the stigma

Muirsical Conversation with Chris Norman

Muirsical Conversation with Chris Norman

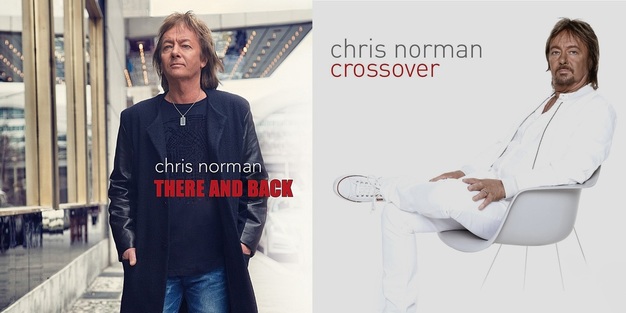

Opening with the chiming lead-off single 'Waiting' (a song that would suit Neil Diamond down to the ground), Chris Norman’s latest album Crossover takes the listener on a journey across a number of different-yet-linked genres including soft rock, pop rock, ballad, country-themed numbers, a bit of gritty rock and roll and a little reminiscing.

It’s also a fitting exclamation point to what is, 40 years on from Chris Norman’s first successful foray in to the Smokie world of pop rock and roll, one of the singer and songwriter’s strongest albums.

However while Chris Norman has enjoyed solo performance and chart album success in a number of territories across the world since leaving Smokie in 1986, it’s a different story in the UK.

Back home in Britain the resurgence in classic rock and pop, a predilection for musical nostalgia, a just-play-the-hits mentality and a girl called Alice have all conspired to make it nigh on impossible for latter day Chris Norman solo material to get the recognition and airplay it deserves.

Chris Norman spoke candidly to FabricationsHQ about the pros and cons of that back in the day success as well as discussing the musical roads travelled on the more recent solo albums that led to Crossover.

But the conversation started with that very album and the well-crafted examples of the musical genres contained within…

Ross Muir: Crossover is an album that could have been sub-titled "This is Chris Norman" because it seems to perfectly express where you are as an artist as well musically encapsulate your favoured musical styles in one package. What inspired the multi-genre approach for this album?

Chris Norman: Well the way I normally write songs is to just start playing around with the guitar or maybe the piano. Then, if I come up with anything I like, I put it on to my iPhone and when it comes to the time that I’m getting ready to record a new album I go through all those ideas that I’ve recorded.

Now, what I used to do was listen to them and pull them out while thinking "that one would be good for the album" of "this one would probably be a good fit" but this time I just picked any song that I thought was a good song and that I liked the sound of, regardless of genre.

It didn’t matter if it was country based or a rock song or a ballad; if I liked the song, I worked it up and recorded it for the album – that was the criteria.

But wasn’t until I had done them all as demos I realised just how many styles there were! [laughs]

For example Cat’s Eyes is a skiffle-type song like Lonnie Donnigan would record and there’s also country, country rock, ballads and a bit of rock and roll in there but I had already decided "sod it; it doesn’t matter because that’s what I’ve written and they are all representative of me as a singer and an artist."

And that’s why I called the album Crossover, because the songs are constantly crossing genres.

RM: One of the highlights of Crossover is the opening track and lead-off music video number, Waiting.

That’s a beautiful slow-build number that musically carries a Heartland Rock feel but lyrically seems to be saying "you can’t always wait for something to happen – go make it happen for yourself…"

CN: Yes, that’s pretty much it. I think everyone is waiting for something pretty much all the time, you know? You might be waiting for the weekend at the end of your nine to five job; or you’re waiting for someone to call you; perhaps you might be waiting for Christmas!

People are always waiting for something and I’m the same – I’m waiting for this and I’m waiting for that and I’m waiting for the new album to come out! [laughs]

Actually the lyrics just sort of came to me after I had come up with the musical idea of the song, which I wrote on a ukulele.

RM: You play the instrument?

CN: Well I sometimes take a ukulele with me when I’m away from home; I put it in my case and that gives me something to play when I’m in a hotel room or a dressing room or wherever.

For Waiting I had that simple [sings] "da-da da-da da-da da-da" repeating riff thing going and then I just thought "no more waiting…"

That’s how it started and when it came to finishing off the song I realised it was about people waiting for something; the lyrics kind of wrote themselves at that point – "The future is now… don’t be afraid."

That’s really the message of the song – you’re doing what you’re doing now, today; the future is already here.

Forget about waiting for stuff, just go out and do it…

It’s also a fitting exclamation point to what is, 40 years on from Chris Norman’s first successful foray in to the Smokie world of pop rock and roll, one of the singer and songwriter’s strongest albums.

However while Chris Norman has enjoyed solo performance and chart album success in a number of territories across the world since leaving Smokie in 1986, it’s a different story in the UK.

Back home in Britain the resurgence in classic rock and pop, a predilection for musical nostalgia, a just-play-the-hits mentality and a girl called Alice have all conspired to make it nigh on impossible for latter day Chris Norman solo material to get the recognition and airplay it deserves.

Chris Norman spoke candidly to FabricationsHQ about the pros and cons of that back in the day success as well as discussing the musical roads travelled on the more recent solo albums that led to Crossover.

But the conversation started with that very album and the well-crafted examples of the musical genres contained within…

Ross Muir: Crossover is an album that could have been sub-titled "This is Chris Norman" because it seems to perfectly express where you are as an artist as well musically encapsulate your favoured musical styles in one package. What inspired the multi-genre approach for this album?

Chris Norman: Well the way I normally write songs is to just start playing around with the guitar or maybe the piano. Then, if I come up with anything I like, I put it on to my iPhone and when it comes to the time that I’m getting ready to record a new album I go through all those ideas that I’ve recorded.

Now, what I used to do was listen to them and pull them out while thinking "that one would be good for the album" of "this one would probably be a good fit" but this time I just picked any song that I thought was a good song and that I liked the sound of, regardless of genre.

It didn’t matter if it was country based or a rock song or a ballad; if I liked the song, I worked it up and recorded it for the album – that was the criteria.

But wasn’t until I had done them all as demos I realised just how many styles there were! [laughs]

For example Cat’s Eyes is a skiffle-type song like Lonnie Donnigan would record and there’s also country, country rock, ballads and a bit of rock and roll in there but I had already decided "sod it; it doesn’t matter because that’s what I’ve written and they are all representative of me as a singer and an artist."

And that’s why I called the album Crossover, because the songs are constantly crossing genres.

RM: One of the highlights of Crossover is the opening track and lead-off music video number, Waiting.

That’s a beautiful slow-build number that musically carries a Heartland Rock feel but lyrically seems to be saying "you can’t always wait for something to happen – go make it happen for yourself…"

CN: Yes, that’s pretty much it. I think everyone is waiting for something pretty much all the time, you know? You might be waiting for the weekend at the end of your nine to five job; or you’re waiting for someone to call you; perhaps you might be waiting for Christmas!

People are always waiting for something and I’m the same – I’m waiting for this and I’m waiting for that and I’m waiting for the new album to come out! [laughs]

Actually the lyrics just sort of came to me after I had come up with the musical idea of the song, which I wrote on a ukulele.

RM: You play the instrument?

CN: Well I sometimes take a ukulele with me when I’m away from home; I put it in my case and that gives me something to play when I’m in a hotel room or a dressing room or wherever.

For Waiting I had that simple [sings] "da-da da-da da-da da-da" repeating riff thing going and then I just thought "no more waiting…"

That’s how it started and when it came to finishing off the song I realised it was about people waiting for something; the lyrics kind of wrote themselves at that point – "The future is now… don’t be afraid."

That’s really the message of the song – you’re doing what you’re doing now, today; the future is already here.

Forget about waiting for stuff, just go out and do it…

RM: You mentioned country based songs when working up tracks for Crossover – that’s a genre that has manifested itself more and more on your albums as your solo career has progressed…

CN: It has, yes, but I didn’t really like country music when I was young.

I grew up in the fifties and my teenage years were the sixties, so I started off listening to Elvis Presley and Little Richard; all those rock and roll guys but with that country influence.

And I listened to the Beatles of course; the Beatles always did different types of songs and I liked that about their albums, it was never just one type or one style of song.

But I did get in to the older type of country as I also got older – Hank Williams, Willie Nelson – I really started to listen to their music.

But when I was younger I didn’t want to listen to Hank Williams or all those guys; I felt it was a bit too corny. But now that I’m older and have a real appreciation for the genre I think it’s fantastic; very simple, very straightforward and just great songs.

I was always in to folk music – the Bob Dylan style of folk music – and I was listening to a lot of Simon and Garfunkel when I was a teenager but like I said it wasn’t until I got older that I really started to appreciate some of those great country classics.

So, yeah, I did get more involved in that genre; a song like The Growing Years and a number of other songs I’ve done reflect there’s a certain kind of country I really do like.

But then I like all kinds of music; there shouldn’t be a barrier about what you do and what you don’t do, musically – I like, and listen to, all kinds of music.

RM: That’s the way it should be. I don’t care if it’s rock, pop, progressive, blues, country or any of the other genres, everyone should start by listening to all types of music and then find what you like and don’t like by the sheer musicality of it, not by its genre.

That’s why your covers album, Time Traveller, works so well – you embraced the best of many eras and genres and have everything in there from Simon and Garfunkel to Take That to Snow Patrol…

CN: Again, that comes down to what I like and what I listen to; I’m not the sort of person who will ever say "I’m only going to listen to this" or "I’m not going to be listening to that." I like all kinds of music.

In fact I wouldn’t mind doing a Frank Sinatra type album one day or another genre specific album.

I think if music moves you in some way – whether it makes you happy or sad or touches something in you – then there’s no reason why you shouldn’t like it, whatever the genre.

And, as a musician, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t perform it.

RM: Returning to Crossover – the album includes a number of lighter rock styles including the beach walking pop rock of Hard to Find, the slow-build ballad Fly Away and a quirky, sci-fi rock and roll number in the shape of Alien Like You.

Collectively, all the Crossover tracks produce a great little album of well-crafted, multi-genre soft-rock.

CN: Thank you for saying that. I must admit when I was recording the demos and starting to get ready to record the album I did think this was a great selection of songs. They may be different styles but each stands on its own right, and for what they are. I’m glad you think that too.

RM: Well you are one of those artists who, vocally and musically, has genuine cross-genre appeal.

But [laughs], I have to be honest and say that, while the album Some Hearts are Diamonds and the single Midnight Lady helped put you on the post-Smokie map, that was just stylised, polished keyboard based Euro-pop that became a stepping stone to more definitive "Chris Norman" albums.

For me you really hit your stride with Interchange in 1991; that’s not just a great Chris Norman album that’s a great singer songwriter album, full stop.

CN: Thank you. Some Hearts are Diamonds, which was 1986, that really wasn’t my thing; it came off the back of the single Midnight Lady, which was just after I left Smokie.

I made that album with Dieter Bohlen, a songwriter and producer who had been in the German pop duo Modern Talking; they had been very big in Europe and were a Euro-pop kind of band.

So because of Midnight Lady, which Dieter had written and produced, the record company wanted me to go in to the studio with him to record an album, which I did.

But it was a compromise album because Dieter was used to a working style where he was in charge of everything; I’d already done the Smokie thing and we were from completely different backgrounds – I had been in a rock and roll guitar band and he was from the keyboard and Euro-pop side of things.

So we agreed to write half the album each, which is what we did, but even then when it came to producing the album I was always saying "we need to put a guitar here" and Dieter would say "oh no, we don’t want a guitar there" [laughs]; so it was difficult from that point of view.

That album was okay for the first solo album after Smokie but it wasn’t an album I was happy with, really.

When it came to the next album Different Shades, which I did with producer Pip Williams, that was more like the stuff I wanted to do – and by the time I got to the Interchange album I’d kind of found the area where I felt more comfortable.

RM: The more Americanised The Growing Years, which followed Interchange, is another good album.

It’s also the album that features your cover of the Eddie Money song Peace in Our Time but while you got to it one year before Cliff Richard it was Sir Cliff that had major hit single success with it…

CN: That was around the time I was looking for songs. I had a few songs which I had written for The Growing Years but I had also been sent a lot of different songs including Peace in Our Time.

I thought it was really good and we recorded it for the record but I don’t think we made the best of that song. We didn’t make it as good as we could have production wise, either; it had a bit of a synthetic sound to it.

So that was the end of Peace in Our Time because while we put it on the record my version didn’t sound like a hit to me.

But then, as you said, Cliff Richard brought a version out about a year after me and he had a huge hit with it! He’d obviously been sent the same tape of songs as me!

RM: Missed opportunities aside what I find refreshing is the transition from that overly polished sound to finding your own style and never doing the same album twice, which is such an easy trap to fall in to, especially if an artist or producer found a successful formula or sound on the previous album.

CN: I’ve tried not to but you can only do what you have in your armoury, you know?

I can only sing as I sing and I can only play as I play but I do try to do something a little bit different each time, so it’s not the same as the last one.

The secret, I think, to any good album is first of all the songs and second of all the production.

How you produce the album and how you record the songs is important and as I’ve gone on I’ve tried to get it back to the roots of that, almost handmade. In fact I had an album called Handmade…

RM: That’s another great little album. It’s a very rocky, primarily up-tempo record with a live feel to the most of the songs and performances. Which is exactly what you are saying...

CN: Yeah; what I always try to do now is get musicians in to really "play."

RM: It’s a musical philosophy that’s paying dividends because over the last four albums you have delivered your most consistent and strongest quartet of releases.

Going back to the first of those four, Close Up – that’s a singer songwriter album cut from the very same mould as Neil Diamond’s 12 Songs album.

Did Neil’s stripped back album have an influence on the sound and style of Close Up?

CN: I wouldn’t say that one record, no, but producer Rick Rubin definitely did with the "American Series" albums he recorded with Johnny Cash.

I really liked those albums and I loved the very stripped down sound; then Rick did 12 Songs with Neil Diamond in a similar, stripped back way.

When I made Close Up I definitely wanted it to be a stripped down album and there’s very little on that album apart from vocals, acoustic piano, guitars and some string arrangements.

So I did try and emulate that kind of stripped back sound; the songs I wrote for Close Up were songs you could play very easily on an acoustic guitar without any accompaniment...

CN: It has, yes, but I didn’t really like country music when I was young.

I grew up in the fifties and my teenage years were the sixties, so I started off listening to Elvis Presley and Little Richard; all those rock and roll guys but with that country influence.

And I listened to the Beatles of course; the Beatles always did different types of songs and I liked that about their albums, it was never just one type or one style of song.

But I did get in to the older type of country as I also got older – Hank Williams, Willie Nelson – I really started to listen to their music.

But when I was younger I didn’t want to listen to Hank Williams or all those guys; I felt it was a bit too corny. But now that I’m older and have a real appreciation for the genre I think it’s fantastic; very simple, very straightforward and just great songs.

I was always in to folk music – the Bob Dylan style of folk music – and I was listening to a lot of Simon and Garfunkel when I was a teenager but like I said it wasn’t until I got older that I really started to appreciate some of those great country classics.

So, yeah, I did get more involved in that genre; a song like The Growing Years and a number of other songs I’ve done reflect there’s a certain kind of country I really do like.

But then I like all kinds of music; there shouldn’t be a barrier about what you do and what you don’t do, musically – I like, and listen to, all kinds of music.

RM: That’s the way it should be. I don’t care if it’s rock, pop, progressive, blues, country or any of the other genres, everyone should start by listening to all types of music and then find what you like and don’t like by the sheer musicality of it, not by its genre.

That’s why your covers album, Time Traveller, works so well – you embraced the best of many eras and genres and have everything in there from Simon and Garfunkel to Take That to Snow Patrol…

CN: Again, that comes down to what I like and what I listen to; I’m not the sort of person who will ever say "I’m only going to listen to this" or "I’m not going to be listening to that." I like all kinds of music.

In fact I wouldn’t mind doing a Frank Sinatra type album one day or another genre specific album.

I think if music moves you in some way – whether it makes you happy or sad or touches something in you – then there’s no reason why you shouldn’t like it, whatever the genre.

And, as a musician, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t perform it.

RM: Returning to Crossover – the album includes a number of lighter rock styles including the beach walking pop rock of Hard to Find, the slow-build ballad Fly Away and a quirky, sci-fi rock and roll number in the shape of Alien Like You.

Collectively, all the Crossover tracks produce a great little album of well-crafted, multi-genre soft-rock.

CN: Thank you for saying that. I must admit when I was recording the demos and starting to get ready to record the album I did think this was a great selection of songs. They may be different styles but each stands on its own right, and for what they are. I’m glad you think that too.

RM: Well you are one of those artists who, vocally and musically, has genuine cross-genre appeal.

But [laughs], I have to be honest and say that, while the album Some Hearts are Diamonds and the single Midnight Lady helped put you on the post-Smokie map, that was just stylised, polished keyboard based Euro-pop that became a stepping stone to more definitive "Chris Norman" albums.

For me you really hit your stride with Interchange in 1991; that’s not just a great Chris Norman album that’s a great singer songwriter album, full stop.

CN: Thank you. Some Hearts are Diamonds, which was 1986, that really wasn’t my thing; it came off the back of the single Midnight Lady, which was just after I left Smokie.

I made that album with Dieter Bohlen, a songwriter and producer who had been in the German pop duo Modern Talking; they had been very big in Europe and were a Euro-pop kind of band.

So because of Midnight Lady, which Dieter had written and produced, the record company wanted me to go in to the studio with him to record an album, which I did.

But it was a compromise album because Dieter was used to a working style where he was in charge of everything; I’d already done the Smokie thing and we were from completely different backgrounds – I had been in a rock and roll guitar band and he was from the keyboard and Euro-pop side of things.

So we agreed to write half the album each, which is what we did, but even then when it came to producing the album I was always saying "we need to put a guitar here" and Dieter would say "oh no, we don’t want a guitar there" [laughs]; so it was difficult from that point of view.

That album was okay for the first solo album after Smokie but it wasn’t an album I was happy with, really.

When it came to the next album Different Shades, which I did with producer Pip Williams, that was more like the stuff I wanted to do – and by the time I got to the Interchange album I’d kind of found the area where I felt more comfortable.

RM: The more Americanised The Growing Years, which followed Interchange, is another good album.

It’s also the album that features your cover of the Eddie Money song Peace in Our Time but while you got to it one year before Cliff Richard it was Sir Cliff that had major hit single success with it…

CN: That was around the time I was looking for songs. I had a few songs which I had written for The Growing Years but I had also been sent a lot of different songs including Peace in Our Time.

I thought it was really good and we recorded it for the record but I don’t think we made the best of that song. We didn’t make it as good as we could have production wise, either; it had a bit of a synthetic sound to it.

So that was the end of Peace in Our Time because while we put it on the record my version didn’t sound like a hit to me.

But then, as you said, Cliff Richard brought a version out about a year after me and he had a huge hit with it! He’d obviously been sent the same tape of songs as me!

RM: Missed opportunities aside what I find refreshing is the transition from that overly polished sound to finding your own style and never doing the same album twice, which is such an easy trap to fall in to, especially if an artist or producer found a successful formula or sound on the previous album.

CN: I’ve tried not to but you can only do what you have in your armoury, you know?

I can only sing as I sing and I can only play as I play but I do try to do something a little bit different each time, so it’s not the same as the last one.

The secret, I think, to any good album is first of all the songs and second of all the production.

How you produce the album and how you record the songs is important and as I’ve gone on I’ve tried to get it back to the roots of that, almost handmade. In fact I had an album called Handmade…

RM: That’s another great little album. It’s a very rocky, primarily up-tempo record with a live feel to the most of the songs and performances. Which is exactly what you are saying...

CN: Yeah; what I always try to do now is get musicians in to really "play."

RM: It’s a musical philosophy that’s paying dividends because over the last four albums you have delivered your most consistent and strongest quartet of releases.

Going back to the first of those four, Close Up – that’s a singer songwriter album cut from the very same mould as Neil Diamond’s 12 Songs album.

Did Neil’s stripped back album have an influence on the sound and style of Close Up?

CN: I wouldn’t say that one record, no, but producer Rick Rubin definitely did with the "American Series" albums he recorded with Johnny Cash.

I really liked those albums and I loved the very stripped down sound; then Rick did 12 Songs with Neil Diamond in a similar, stripped back way.

When I made Close Up I definitely wanted it to be a stripped down album and there’s very little on that album apart from vocals, acoustic piano, guitars and some string arrangements.

So I did try and emulate that kind of stripped back sound; the songs I wrote for Close Up were songs you could play very easily on an acoustic guitar without any accompaniment...

RM: After Close Up came Time Traveller, which we touched on earlier. That’s a great set of covers that crosses both the genres and the decades. What influenced the particular song choices?

CN: They were just songs that I liked; it really was as simple as that.

That album came about because the record label I was with at the time suggested that I do a covers album…

RM: You’re hardly the first and are far from the last to have the "covers" request made of them…

CN: Right, and that’s why I wasn’t sure it was a good idea because so many people had done it by then.

But in the end we said "right, okay, we’ll do the covers album but I want to make sure the songs we do are not from any one era."

My favourite songs of all time probably come from the sixties – that’s when I was a teenager and that’s the stuff you usually feel closest to – but there are loads of songs from after that era I really like too.

So I ended up with this huge list of forty songs [laughs], which I then went through and tried singing.

But there were lots of songs I loved that didn’t really suit my voice and there were also a lot that I didn’t know how to change, because they were already perfect! Sometimes you take someone else’s song and you just can’t find a way to change it – at least not in a good way!

So I had to cross a lot of songs off the list but the songs that I picked are still songs that I really loved as well as ones I felt I could do something different with.

RM: It’s an album that also proves a good song is a good song, although rock fans are particularly guilty, sadly, of putting blinkers up or ear-plugs in if you announce a song by, say, Take That – then all bets are off.

But as we discussed earlier good music is good music; it doesn’t matter what genre it originated from.

CN: Exactly. Take a song like Back for Good – the original production was very luscious and boy bandish but I wanted to take it back and give it a sort of simple Al Green atmosphere, which is what we tried to do.

And the way I recorded that whole album was to basically get a bunch of really good musicians in – there were five of us in the studio – to record the tracks live.

I was in a sectioned off area and the others were separated so we could get the sound we wanted but we pretty much recorded it live in the studio like that. There were a couple of overdubs in there but quite a lot of the vocals were done as we recorded the tracks; even the arrangements were done on the fly.

That’s how Get It On was recorded, which is the first song on that album. Get It On by T-Rex was a great example of whatever you want to call that big chart-rock sound of the seventies but to me it was just a great twelve-bar rhythm and blues song – so that’s how we did it.

And we played it live, with the guitar player just adding those bluesy licks and the solo as we were putting it down!

RM: Following Time Traveller there was a real return to rockier roots with There and Back, the album that precedes Crossover. You’re not hanging about on songs such as I’m Gone, Whisky and Water and Hot Love. There’s some seriously solid rock and roll on that album…

CN: There and Back was similar to Time Traveller in that we recorded it as close to live as we could.

For that one I got my touring band in and said "if you’ve got any song ideas let me hear them and we can all get involved in the song writing."

Everybody in the band had a few pieces – not finished songs, just song ideas – and we ended up with about seven songs on There and Back that I wrote with members of the band.

CN: They were just songs that I liked; it really was as simple as that.

That album came about because the record label I was with at the time suggested that I do a covers album…

RM: You’re hardly the first and are far from the last to have the "covers" request made of them…

CN: Right, and that’s why I wasn’t sure it was a good idea because so many people had done it by then.

But in the end we said "right, okay, we’ll do the covers album but I want to make sure the songs we do are not from any one era."

My favourite songs of all time probably come from the sixties – that’s when I was a teenager and that’s the stuff you usually feel closest to – but there are loads of songs from after that era I really like too.

So I ended up with this huge list of forty songs [laughs], which I then went through and tried singing.

But there were lots of songs I loved that didn’t really suit my voice and there were also a lot that I didn’t know how to change, because they were already perfect! Sometimes you take someone else’s song and you just can’t find a way to change it – at least not in a good way!

So I had to cross a lot of songs off the list but the songs that I picked are still songs that I really loved as well as ones I felt I could do something different with.

RM: It’s an album that also proves a good song is a good song, although rock fans are particularly guilty, sadly, of putting blinkers up or ear-plugs in if you announce a song by, say, Take That – then all bets are off.

But as we discussed earlier good music is good music; it doesn’t matter what genre it originated from.

CN: Exactly. Take a song like Back for Good – the original production was very luscious and boy bandish but I wanted to take it back and give it a sort of simple Al Green atmosphere, which is what we tried to do.

And the way I recorded that whole album was to basically get a bunch of really good musicians in – there were five of us in the studio – to record the tracks live.

I was in a sectioned off area and the others were separated so we could get the sound we wanted but we pretty much recorded it live in the studio like that. There were a couple of overdubs in there but quite a lot of the vocals were done as we recorded the tracks; even the arrangements were done on the fly.

That’s how Get It On was recorded, which is the first song on that album. Get It On by T-Rex was a great example of whatever you want to call that big chart-rock sound of the seventies but to me it was just a great twelve-bar rhythm and blues song – so that’s how we did it.

And we played it live, with the guitar player just adding those bluesy licks and the solo as we were putting it down!

RM: Following Time Traveller there was a real return to rockier roots with There and Back, the album that precedes Crossover. You’re not hanging about on songs such as I’m Gone, Whisky and Water and Hot Love. There’s some seriously solid rock and roll on that album…

CN: There and Back was similar to Time Traveller in that we recorded it as close to live as we could.

For that one I got my touring band in and said "if you’ve got any song ideas let me hear them and we can all get involved in the song writing."

Everybody in the band had a few pieces – not finished songs, just song ideas – and we ended up with about seven songs on There and Back that I wrote with members of the band.

There and Back (2013) is the perfect rock based complement to the lighter and multi-genre Crossover.

Along with the stripped back Close Up (2007) and the primarily live-in-the-studio covers album Time Traveller (2011), they make up Chris Norman's most consistent and strongest quartet of releases.

CN: For There and Back I also wrote with Pete Spencer, who had been the drummer and my writing partner in Smokie when I was with the band. Pete’s still a close friend of mine and we wrote a couple of songs together for the first time in years, which are also on the album.

RM: Just a great set of songs all round; as I said earlier the last four albums you have released are four of your strongest and most consistent works.

CN: Thank you – I must be starting late! [laughs]

RM: Listen, you’re still a youngster in terms of the rock veterans still performing in the 21st century.

Look at the number of septuagenarians still playing and John Mayall, at 81 years young, is still singing and playing the blues.

Who among us ever thought this would be the rock and roll reality, forty and fifty years on?

CN: Oh none of us did. I did an interview back in 1978 for a Smokie documentary and it’s an interview that keeps coming back at me because people keep reminding me about it [laughs].

On that interview I said something like "I can’t imagine I’ll be doing this for the rest of my life; I can’t see me at fifty-six still trying to play rock music!" [laughter]

But back then you didn’t know that people would be doing just that; it hadn’t happened yet.

And now that I’m in my mid sixties it seems ridiculous to have said that but I didn’t know that would be the reality when I was twenty-eight!

RM: Keeping to the present but nodding to that Smokie past Crossover, rather fittingly, closes with a remix of 40 Years On, the soft rock number you wrote and recorded for the recent Smokie Gold Anthology.

Smokie, of course, were no strangers to success in the mid seventies and early eighties – happy memories of that band and those days?

CN: Oh absolutely. We were a band where three of us – me, Pete Spencer and Alan Silson – had all known each other from our school days; Terry Uttley, who we also knew, joined a little bit later on.

For a few years we tried to make it with different records, but all of them flopped!

That was under the name Kindness but when we changed the name to Smokie and signed to Mickie Most’s RAK records we started to have a bit of success and some hits.

That was a great time; we went on to travel all over the world and played some huge shows – especially in Germany, where we did arena tours.

As a band we also got on great; were like brothers and we achieved what we set out to do – or it certainly felt like that at the time – and that whole period helped to put me on the first step of the ladder that allowed me to continue and turn it into a solo career.

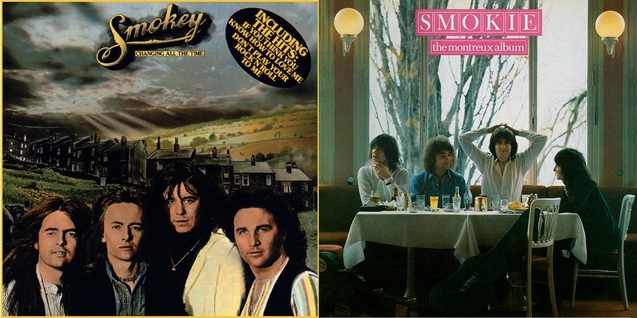

RM: While Smokie's biggest successes were the Chinn and Chapman hits you were a solid album band, too. The second album, Changing All the Time, is a great pop rock and harmonies record and I rate The Montreux Album as one of the best light rock albums of the late-seventies era.

CN: Thank you. When you’re working with a team like Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman – especially Mike who was the musical side of that team and the producer – you are always competing because you are looking to beat their song, which is almost certainly going to be put out as the single.

But that was very difficult because apart from the fact they were very good at it they had a massive track record and the record company is always going to lean towards their material.

So we tried to write songs that could be as good as theirs or would at least be considered for the next single, and after a while we did have a couple, like Mexican Girl.

But it was great to have that kind of writing experience around you – I learned more from Mike Chapman about writing songs and producing records than anyone else I’ve ever worked with.

RM: Chinn and Chapman were a formidable hit making team but there is also what became known as "The Chinnichap Curse" where bands’ under Nicky and Mike's song writing wing got so tied in to the Chinnichap conveyor belt of hit singles that their own material became almost forgotten or a distant second.

CN: And I don’t know why that is, with Smokie, because we were a good live band too.

We were a solid band in the studio and we were a solid band live; we wrote some decent songs and recorded some decent albums like, as you said, The Montreux Album.

Along with the stripped back Close Up (2007) and the primarily live-in-the-studio covers album Time Traveller (2011), they make up Chris Norman's most consistent and strongest quartet of releases.

CN: For There and Back I also wrote with Pete Spencer, who had been the drummer and my writing partner in Smokie when I was with the band. Pete’s still a close friend of mine and we wrote a couple of songs together for the first time in years, which are also on the album.

RM: Just a great set of songs all round; as I said earlier the last four albums you have released are four of your strongest and most consistent works.

CN: Thank you – I must be starting late! [laughs]

RM: Listen, you’re still a youngster in terms of the rock veterans still performing in the 21st century.

Look at the number of septuagenarians still playing and John Mayall, at 81 years young, is still singing and playing the blues.

Who among us ever thought this would be the rock and roll reality, forty and fifty years on?

CN: Oh none of us did. I did an interview back in 1978 for a Smokie documentary and it’s an interview that keeps coming back at me because people keep reminding me about it [laughs].

On that interview I said something like "I can’t imagine I’ll be doing this for the rest of my life; I can’t see me at fifty-six still trying to play rock music!" [laughter]

But back then you didn’t know that people would be doing just that; it hadn’t happened yet.

And now that I’m in my mid sixties it seems ridiculous to have said that but I didn’t know that would be the reality when I was twenty-eight!

RM: Keeping to the present but nodding to that Smokie past Crossover, rather fittingly, closes with a remix of 40 Years On, the soft rock number you wrote and recorded for the recent Smokie Gold Anthology.

Smokie, of course, were no strangers to success in the mid seventies and early eighties – happy memories of that band and those days?

CN: Oh absolutely. We were a band where three of us – me, Pete Spencer and Alan Silson – had all known each other from our school days; Terry Uttley, who we also knew, joined a little bit later on.

For a few years we tried to make it with different records, but all of them flopped!

That was under the name Kindness but when we changed the name to Smokie and signed to Mickie Most’s RAK records we started to have a bit of success and some hits.

That was a great time; we went on to travel all over the world and played some huge shows – especially in Germany, where we did arena tours.

As a band we also got on great; were like brothers and we achieved what we set out to do – or it certainly felt like that at the time – and that whole period helped to put me on the first step of the ladder that allowed me to continue and turn it into a solo career.

RM: While Smokie's biggest successes were the Chinn and Chapman hits you were a solid album band, too. The second album, Changing All the Time, is a great pop rock and harmonies record and I rate The Montreux Album as one of the best light rock albums of the late-seventies era.

CN: Thank you. When you’re working with a team like Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman – especially Mike who was the musical side of that team and the producer – you are always competing because you are looking to beat their song, which is almost certainly going to be put out as the single.

But that was very difficult because apart from the fact they were very good at it they had a massive track record and the record company is always going to lean towards their material.

So we tried to write songs that could be as good as theirs or would at least be considered for the next single, and after a while we did have a couple, like Mexican Girl.

But it was great to have that kind of writing experience around you – I learned more from Mike Chapman about writing songs and producing records than anyone else I’ve ever worked with.

RM: Chinn and Chapman were a formidable hit making team but there is also what became known as "The Chinnichap Curse" where bands’ under Nicky and Mike's song writing wing got so tied in to the Chinnichap conveyor belt of hit singles that their own material became almost forgotten or a distant second.

CN: And I don’t know why that is, with Smokie, because we were a good live band too.

We were a solid band in the studio and we were a solid band live; we wrote some decent songs and recorded some decent albums like, as you said, The Montreux Album.

Changing All the Time (note the original band name spelling, curio lovers) is a fine example of Crosby

Stills & Nash styled pop rock and harmonies; the changing musical times of the late 70s however meant The Montreux Album, one of the best light rock albums of that era, never got the recognition it deserved.

RM: Another downside to that "curse" is while territories such as Scandinavia and Germany have supported your music since you went solo in 1986, here in the UK you are haunted by the Ghost of Smokie Past and a girl called Alice that you haven’t lived next door to for thirty-nine years…

CN: I think you’re right because while Smokie had lots of hits and great songs like If You Think You Know How to Love Me – a west coast, almost Eagles or Crosby Stills & Nash style of song – people in the UK only seem to want to remember Living Next Door to Alice, a song we did under a kind of protest…

RM: Really? I'd never become aware of that...

CN: Yeah, we were in America recording the Midnight Café album and had it pretty much sorted, song wise, when Mike Chapman said "why don’t we record Living Next Door to Alice as a single?"

We said "No, it’s too schmaltzy; it’s too pop-country and western" but we agreed to do it because the idea was we would put it on the American version of the album but not the UK version.

So it was to be added to the American album with a view to maybe pushing it in to the country charts, because having a song in the American country charts is something we didn’t object to at all.

So we recorded it, it sounded pretty good – and was obviously very catchy – but when we brought it and the album back to the UK the distribution label, EMI, said "we want to go with that one; we want to put Living Next Door to Alice out as the single here."

And I remember having a meeting with Mickie Most in his office and really arguing against it but he said "look guys it’s going to be a big hit – in fact it’s going to be a massive hit" and while that was as may be it wasn’t really the direction we wanted to go in.

Anyway, we lost that battle, Mickie was right and now it all sounds like sour grapes [laughs] because it was good for us – it was a Number One all over Europe and in Australia; it made Number Five in the UK and it became a Top 25 Billboard hit in America.

But it did leave us – and now me – with this stigma attached, because people only seem to remember that song.

I often think that’s why we’re overlooked when you see some of those seventies music programmes they put together; we rarely feature in those yet I see people or bands in those programmes that had one, maybe two, hits – and we had a dozen in the UK alone.

And I do think that’s because the band Smokie are looked upon as a manufactured pop group; there were quite a few around in the seventies but we weren’t one of them – we were not that but that’s how we were perceived.

RM: And as regards that stigma and your own situation in the UK – is there a part of you that thinks:

"You know what guys, whatever you may think that was decades ago. I have twenty-plus solo records here; how about some recognition for that?"

CN: That is what I think, yes. That stigma has gone in territories like Scandinavia and countries like Germany; I also go all over the Eastern Bloc and Australia and that whole Alice thing has gone there, too.

But in the UK it’s there still and I do feel that haunts both of us a bit – which is a shame because that’s not what we were as a band and it’s certainly not what I am now.

As it turned out Living Next Door to Alice was a good song but then of course they rerecorded it about twenty years later with the "Who the fuck is Alice?" bit in it and... [sighs] well, it is what it is.

You can’t do anything about it now but I wouldn’t have done it if I had still been in the band; I would have said "no way are we going to do that."

RM: Compounding the issue is the number of people who associate you with that version, even although you were nine years and the same number of solo albums removed from the band by then.

CN: That certainly doesn’t help and we had major differences of opinion when that version came out.

I remember talking to Terry and Alan when they were about to release it and saying to them "don’t do this!" But they did [laughs]; Alan left the band about a year after that and I think he wishes he hadn’t done it now, either.

RM: That whole Alice stigma and the related apathy in the UK towards your near thirty years and counting solo career is why I continue to cite you as one of the most under-rated, under appreciated and under valued soft rock singer songwriters this country has produced.

CN: You put that in your review of Crossover, which I saw a couple of days ago – thank you for saying that and thank you very much for the review by the way – but I must tell you when I showed that to my wife she said "did you write this?" [laughter].

RM: Well you can tell her I wasn’t on commission but I will take five percent of all Crossover sales – cheque will be fine [laughter].

As we start to wrap up I’d like to talk a little about you vocally. You’re still in fine and distinct voice and you are singing rounder now than you did back in the day – to the extent that the famous crackle across the vowels has diminished. Do you do anything specific to look after the singing voice?

CN: I don’t do anything, and I never did. The croakiness thing is interesting because I didn’t start off with a croaky voice. When I was a kid, about eleven, I used to sing in choirs and had a purer style of singing voice. The croakier vocal began when I started to play in groups and singing rock and roll numbers like Lucille; songs where I was pushing my voice more.

I was playing nearly every night back then so that croakier vocal started to develop and as you get older your voice, or voice box, seems to get thicker.

You can hear it in other singers too, especially the likes of Rod Stewart and Paul McCartney – their voices changed texture a bit as they got older and mine has too.

If I’m in the middle of a tour I will start to sound more like I used to [laughs] and I still have that croakiness, but now it depends on the type of song I’m singing or if I’m pushing more.

But I’ve also got, as you said, a more rounded sound to my voice now.

RM: Which is why that croakiness is now only evident on the notes or vowel lines where you are pushing on the rockier material or delivering from the throat and not the modal voice.

And if that’s not a hint to outro with the vocally and musically unsubtle rock and roll of Love’s On Fire I don’t know what is [laughs]. Good way to finish?

CN: That would be great and thank you very much!

Stills & Nash styled pop rock and harmonies; the changing musical times of the late 70s however meant The Montreux Album, one of the best light rock albums of that era, never got the recognition it deserved.

RM: Another downside to that "curse" is while territories such as Scandinavia and Germany have supported your music since you went solo in 1986, here in the UK you are haunted by the Ghost of Smokie Past and a girl called Alice that you haven’t lived next door to for thirty-nine years…

CN: I think you’re right because while Smokie had lots of hits and great songs like If You Think You Know How to Love Me – a west coast, almost Eagles or Crosby Stills & Nash style of song – people in the UK only seem to want to remember Living Next Door to Alice, a song we did under a kind of protest…

RM: Really? I'd never become aware of that...

CN: Yeah, we were in America recording the Midnight Café album and had it pretty much sorted, song wise, when Mike Chapman said "why don’t we record Living Next Door to Alice as a single?"

We said "No, it’s too schmaltzy; it’s too pop-country and western" but we agreed to do it because the idea was we would put it on the American version of the album but not the UK version.

So it was to be added to the American album with a view to maybe pushing it in to the country charts, because having a song in the American country charts is something we didn’t object to at all.

So we recorded it, it sounded pretty good – and was obviously very catchy – but when we brought it and the album back to the UK the distribution label, EMI, said "we want to go with that one; we want to put Living Next Door to Alice out as the single here."

And I remember having a meeting with Mickie Most in his office and really arguing against it but he said "look guys it’s going to be a big hit – in fact it’s going to be a massive hit" and while that was as may be it wasn’t really the direction we wanted to go in.

Anyway, we lost that battle, Mickie was right and now it all sounds like sour grapes [laughs] because it was good for us – it was a Number One all over Europe and in Australia; it made Number Five in the UK and it became a Top 25 Billboard hit in America.

But it did leave us – and now me – with this stigma attached, because people only seem to remember that song.

I often think that’s why we’re overlooked when you see some of those seventies music programmes they put together; we rarely feature in those yet I see people or bands in those programmes that had one, maybe two, hits – and we had a dozen in the UK alone.

And I do think that’s because the band Smokie are looked upon as a manufactured pop group; there were quite a few around in the seventies but we weren’t one of them – we were not that but that’s how we were perceived.

RM: And as regards that stigma and your own situation in the UK – is there a part of you that thinks:

"You know what guys, whatever you may think that was decades ago. I have twenty-plus solo records here; how about some recognition for that?"

CN: That is what I think, yes. That stigma has gone in territories like Scandinavia and countries like Germany; I also go all over the Eastern Bloc and Australia and that whole Alice thing has gone there, too.

But in the UK it’s there still and I do feel that haunts both of us a bit – which is a shame because that’s not what we were as a band and it’s certainly not what I am now.

As it turned out Living Next Door to Alice was a good song but then of course they rerecorded it about twenty years later with the "Who the fuck is Alice?" bit in it and... [sighs] well, it is what it is.

You can’t do anything about it now but I wouldn’t have done it if I had still been in the band; I would have said "no way are we going to do that."

RM: Compounding the issue is the number of people who associate you with that version, even although you were nine years and the same number of solo albums removed from the band by then.

CN: That certainly doesn’t help and we had major differences of opinion when that version came out.

I remember talking to Terry and Alan when they were about to release it and saying to them "don’t do this!" But they did [laughs]; Alan left the band about a year after that and I think he wishes he hadn’t done it now, either.

RM: That whole Alice stigma and the related apathy in the UK towards your near thirty years and counting solo career is why I continue to cite you as one of the most under-rated, under appreciated and under valued soft rock singer songwriters this country has produced.

CN: You put that in your review of Crossover, which I saw a couple of days ago – thank you for saying that and thank you very much for the review by the way – but I must tell you when I showed that to my wife she said "did you write this?" [laughter].

RM: Well you can tell her I wasn’t on commission but I will take five percent of all Crossover sales – cheque will be fine [laughter].

As we start to wrap up I’d like to talk a little about you vocally. You’re still in fine and distinct voice and you are singing rounder now than you did back in the day – to the extent that the famous crackle across the vowels has diminished. Do you do anything specific to look after the singing voice?

CN: I don’t do anything, and I never did. The croakiness thing is interesting because I didn’t start off with a croaky voice. When I was a kid, about eleven, I used to sing in choirs and had a purer style of singing voice. The croakier vocal began when I started to play in groups and singing rock and roll numbers like Lucille; songs where I was pushing my voice more.

I was playing nearly every night back then so that croakier vocal started to develop and as you get older your voice, or voice box, seems to get thicker.

You can hear it in other singers too, especially the likes of Rod Stewart and Paul McCartney – their voices changed texture a bit as they got older and mine has too.

If I’m in the middle of a tour I will start to sound more like I used to [laughs] and I still have that croakiness, but now it depends on the type of song I’m singing or if I’m pushing more.

But I’ve also got, as you said, a more rounded sound to my voice now.

RM: Which is why that croakiness is now only evident on the notes or vowel lines where you are pushing on the rockier material or delivering from the throat and not the modal voice.

And if that’s not a hint to outro with the vocally and musically unsubtle rock and roll of Love’s On Fire I don’t know what is [laughs]. Good way to finish?

CN: That would be great and thank you very much!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Chris Norman

September 2015

Crossover is out now on Solo Sound Records on CD and digital download.

FabricationsHQ also recommends:

Smokie:

Changing All the Time (1975)

The Montreux Album (1978)

Chris Norman:

Interchange (1991)

Handmade (2003)

Close Up (2007)

Time Traveller (2011)

There and Back (2013)

Chris Norman official website: www.chris-norman.co.uk

Audio tracks presented to accompany the above article and to promote the work of the artist.

No infringement of copyright is intended.

Photo credit: www.chris-norman.co.uk/press/

Muirsical Conversation with Chris Norman

September 2015

Crossover is out now on Solo Sound Records on CD and digital download.

FabricationsHQ also recommends:

Smokie:

Changing All the Time (1975)

The Montreux Album (1978)

Chris Norman:

Interchange (1991)

Handmade (2003)

Close Up (2007)

Time Traveller (2011)

There and Back (2013)

Chris Norman official website: www.chris-norman.co.uk

Audio tracks presented to accompany the above article and to promote the work of the artist.

No infringement of copyright is intended.

Photo credit: www.chris-norman.co.uk/press/