The Manhattan Blues Positivity

Muirsical Conversation with Steve Hunter

Guitarist Steve Hunter is probably best known for his time as a Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal with Lou Reed and putting his six-string stamp on a number of classic Alice Cooper albums including Welcome to My Nightmare, Goes to Hell and Alice Cooper Live.

Hunter is also a sought after session musician and has been a featured or guest guitarist on many an album by artists as diverse as Aerosmith, Peter Gabriel and Glen Campbell.

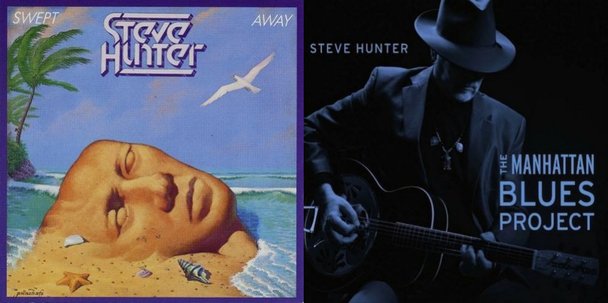

Yet for all his outstanding contributions as summarised above, many of Steve Hunter’s finest musical moments are to be found on his predominately instrumental solo albums, beginning with the critically acclaimed Swept Away in 1977.

In 2013 Steve Hunter released solo album number five, The Manhattan Blues Project, an instrumental set of tone poems inspired by some of the most notable landmarks in New York City’s famous borough.

Steve Hunter sat down with FabricationsHQ to discuss his guitar style, playing with Lou Reed and Alice Cooper, the thorny issue of uncredited session work and The Manhattan Blues Project.

And that’s exactly where we started, discussing Steve’s musical images of Manhattan…

Ross Muir: I believe The Manhattan Blue Project, which you released earlier this year, is your crowning achievement – thus far – as a solo artist. I’m sure you must be extremely proud of that album.

Steve Hunter: Thank you, I actually am very proud of that album and very happy how it came out.

It’s something I’ve always wanted to do; it just took a while before everything got aligned so I could do it!

RM: It’s a very visual album; a collection of musical pictures with the songs inspired by areas and landmarks around Manhattan. But what kick-started it all off? What put you in that Manhattan mind-set?

SH: Well, it started one day I when was on Facebook! One beautiful spring day a couple of years ago a photographer friend of mine, Carrie, grabbed her camera and just went roaming around Manhattan taking photographs. She posted a couple of them on Facebook and one of the photographs was a picture of a sunset in Central Park.

It was just a beautiful picture and, as I was looking at the photograph, I started hearing an idea for a song!

It was almost like the song became the soundtrack to the picture; it was a really strange experience but I went and grabbed the guitar and roughed out the chords and the chord progression and that’s basically how it got started.

Hunter is also a sought after session musician and has been a featured or guest guitarist on many an album by artists as diverse as Aerosmith, Peter Gabriel and Glen Campbell.

Yet for all his outstanding contributions as summarised above, many of Steve Hunter’s finest musical moments are to be found on his predominately instrumental solo albums, beginning with the critically acclaimed Swept Away in 1977.

In 2013 Steve Hunter released solo album number five, The Manhattan Blues Project, an instrumental set of tone poems inspired by some of the most notable landmarks in New York City’s famous borough.

Steve Hunter sat down with FabricationsHQ to discuss his guitar style, playing with Lou Reed and Alice Cooper, the thorny issue of uncredited session work and The Manhattan Blues Project.

And that’s exactly where we started, discussing Steve’s musical images of Manhattan…

Ross Muir: I believe The Manhattan Blue Project, which you released earlier this year, is your crowning achievement – thus far – as a solo artist. I’m sure you must be extremely proud of that album.

Steve Hunter: Thank you, I actually am very proud of that album and very happy how it came out.

It’s something I’ve always wanted to do; it just took a while before everything got aligned so I could do it!

RM: It’s a very visual album; a collection of musical pictures with the songs inspired by areas and landmarks around Manhattan. But what kick-started it all off? What put you in that Manhattan mind-set?

SH: Well, it started one day I when was on Facebook! One beautiful spring day a couple of years ago a photographer friend of mine, Carrie, grabbed her camera and just went roaming around Manhattan taking photographs. She posted a couple of them on Facebook and one of the photographs was a picture of a sunset in Central Park.

It was just a beautiful picture and, as I was looking at the photograph, I started hearing an idea for a song!

It was almost like the song became the soundtrack to the picture; it was a really strange experience but I went and grabbed the guitar and roughed out the chords and the chord progression and that’s basically how it got started.

SH: I also happened to be working on a version of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On at the time because that’s always been one of my favourite all-time songs.

And it’s a song that has always sounded like New York City to me, even though I know that’s not what it’s supposed to be about – it’s supposed to be about the Vietnam War and things that were going on in the late 60’s and early 70’s.

But the production and the arrangement and the way it’s performed, it just feels like Manhattan to me.

I wanted to do a version because I liked the song but, when I listened to it in conjunction with Sunset in Central Park, it just sounded like Manhattan!

RM: That’s really interesting because something I wanted to talk about are the covers on the album, particularly What’s Going On. My first thought on hearing your version was that you had a really perfect fit for the soundscapes you created on the album.

And you’re absolutely right; it feels like it should be on an album about Manhattan, which is extraordinary.

SH: Yeah, and it’s really strange because I know that’s probably not what Marvin Gaye intended.

I don’t even think it was produced or recorded in New York – I think it was recorded in Detroit or L.A.

But the performance, the sound of it and everything about it just sounds like Manhattan to me.

RM: I think also though, and credit where credit’s due, it falls into place because of your skill as a guitarist. That song is quite poignant lyrically, but obviously you are expressing the song instrumentally through your phrasing, tone and touch. And it’s not just the notes you are playing – it’s where you place them.

SH: Why thank you. It’s sometimes a conscious choice and sometimes an unconscious choice, but it’s just the way I’ve learned to play. I learned to play guitar off of B.B. King blues records, basically, and he has such a touch; he has an amazing touch on guitar. And amazing phrasing.

So that’s where I learned just how important phrasing was and how important silence was – the silence between notes is just as important, and sometimes even more important, than the notes themselves.

RM: Absolutely.

SH: So I learned all that from B.B. King, because he has always had this beautiful knack for phrases that sound very vocal; he plays the way he sings, which is really cool.

But so does Albert King and a lot of those early blues guys; I think that is in me by osmosis (laughs).

As I evolved as a player that all just got pulled in; now it’s a major part of my playing.

RM: It’s part of your musical DNA, I would suggest.

SH: Yeah, you’re right.

RM: So, with all that in mind, do you think a twenty-five or thirty year old Steve Hunter could play what you play on The Manhattan Blues Project?

SH: No, I don’t think so. I think there had to be an evolution there and I don’t think I could have played this album when I was twenty-five or thirty, because of where I was then to where I am now.

But as I was saying, the stuff from B.B. King was in there but at twenty, twenty-five and thirty I was still into rock and roll – but it was blues based rock and roll so it was still melody oriented.

It wasn’t always just jamming, although that was a part of it, but over several years it’s been this evolution.

I did try my hand at shredding when shredding became all the rage. I really did, but it just never worked for me or my fingers – I didn’t like it and my fingers just didn’t like it! (laughs). It just didn’t fit me.

I love what those guys can do; when I listen to Joe Satriani or Steve Vai or any of those types of players it’s wonderful, just amazing! But it’s just not me, so I stopped fighting it and said “well, I gotta play the way I play. Whatever comes out, that’s what it is!” (laughs).

RM: You touched there on the talents of Joe Satriani; The Manhattan Blues Project has a very notable list of guest musicians playing on the album including Satriani and Marty Friedman.

Marty and Joe are not exactly slouches when it comes to running fingers up and down a fretboard (laughs), so it must have been quite exciting to have that contrast of your own style then these guys putting down their own licks…

SH: Oh it was amazing! When I wrote the song Twilight in Harlem I said to my wife Karen “it would be great if we could get Satriani to play!”I was actually trying to get Joe and Steve Vai, because they know each other and Steve was a student of Joe’s for a while. So I was trying to get Steve but he was out on the road; when I tried to contact him he was in Russia so I figured that wasn’t going to work (laughs).

Then I asked my friend Jason Becker who he thought would be great to follow Joe and he was the one that thought of Marty Friedman. And when he said Marty’s name I thought “of course!”

I didn’t know Marty that well but Jason does; he was the one that broke the ice between the two of us.

So I contacted Marty and he was into it but, but when I wrote the solos I actually wrote them with Joe Satriani and Steve Vai in mind. But I was a little worried when I wrote those solos because what would happen if neither of them could do it? (laughs).

But I really wanted that contrast between the way I play and the way they play.

RM: Jason Becker's association with Marty goes back to when they played together in the eighties in the heavy metal band Cacophony. But for those that don’t know we should also say that Jason was an extraordinarily talented guitarist until tragically struck down with Motor Neurone Disease, known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease in the United States.

SH: That’s right, ALS, yeah.

RM: His story of survival is absolutely inspirational. And he is still composing?

SH: Yeah, he’s still composing and every once in a while he’ll send me something that he’s working on; he’s still writing the most beautiful stuff. I knew Jason when he was well. We were pals and hung out together in Vancouver when we were working on the David Lee Roth album A Little Ain’t Enough.

We had a great time together but I have eyesight problems so we were making fun of each other’s lameness (laughs). And while that was funny for a time Jason’s health became very serious very quickly and it got to the point where he couldn’t even breathe on his own.

He went through all the anger, all the frustration and the depression, but he worked through all that stuff keeping his great sense of humour the whole time – he and I used to tease each other all the time and just crack each other up. And we still do!

You should read some of the emails we send back and forth – some of them are pretty disgusting (laughter) but they are hilarious! We have such a great time. I love him to death and he’s one of my best friends.

And through all that the music is still in there and he finds ways to get it out.

RM: Fantastic; such an inspiration as regards what can still be achieved, no matter what life throws at you.

I don’t know Jason but from what I’ve read, what he makes of his life and what you have just said it’s clear he’s quite an individual and a wonderful character.

SH: If you ever met him you would never forget him. He’s one of the most incredible human beings on the planet and he inspires me every day. All I have to do is think about my bad eyes and how bad I have it and “oh poor, poor me,” and then I think of Jason and say “what the hell’s the matter with you? There’s nothing wrong with you!”

RM: Yes, it’s such a great leveller. My wife Anne used to work in the Care profession, looking after people with learning difficulties, dementia and physical disabilities.

One particular girl was paraplegic and couldn’t communicate very well but she had a wicked sense of humour and would laugh like a drain at jokes she heard. I would sometimes talk to her for a few minutes, telling jokes, while thinking “I have absolutely no problems worth worrying about.”

SH: I think that’s wonderful; I think that’s really moral. I think we tend to forget that we all have some sort of compromise – there’s always something that we can’t do. Maybe not an affliction, just something we can’t do we wish we could do. I think that’s universal.

So when you see a guy like Jason, whose dream is to make music – and it doesn’t make any difference what the hell gets thrown at him – he still finds a way to make that music.

That just makes it so much easier for everybody else. That’s why he’s such a great inspiration.

RM: And you paid him a nice compliment by recording his short piece Daydream by the Hudson for the album; that’s a lovely little interlude.

SH: That’s a beautiful piece. When I was about at the middle of the album I asked Jason if he had any little musical bits that I could make into something and, if he did, to send some stuff over.

So we got on Skype one day – his nurse can read his eye movements so we can talk back and forth – and we went through about twenty or thirty little pieces of music. I took the ones I thought were pretty cool and stuck them on my desktop.

When I got towards the end of the album I thought “I want to do something with Jason” and I went through all the pieces he had sent me. There was a lot of cool little stuff, but the one that became Daydream by the Hudson just stood out. I did a little editing but nothing serious – I just cut it so it had a nice cadence, put some guitars on it and it’s just this really beautiful piece of music.

RM: It’s a lovely little addition to the album. The other cover on the album is, like What’s Going On, a renowned piece in pop and rock terms – Peter Gabriel’s Solsbury Hill.

You’re revisiting the song of course because you played on the original, but on The Manhattan Blues Project you put your own instrumental take on it.

SH: Now the reason that song’s on the album is a little bit more obscure; a lot of people are going to be thinking “what the hell is Solsbury Hill doing on there?” (laughs).

But the reason it’s on the album is because when we were rehearsing to do Peter’s first ever solo tour, the rehearsals were all in Manhattan. And every time I hear the song it just reminds me of Manhattan; going back and forth from the hotel to the rehearsal, sometimes going out to dinner after rehearsing – just really good memories of Peter and rehearsing to do his tour.

And, yes, plus the fact I did play the acoustic guitar parts on the original; I wanted to kind of revisit those parts on my own album and make it an instrumental song. I think the melody is so cool that it works as an instrumental song, but I was a little concerned at first because Peter writes such brilliant lyrics.

So I was a little worried about not having those lyrics on there but once I started working on it I could see that the melody was strong enough to work by itself – just as a melody.

RM: But that goes back to your own melodic tone, Steve, and that expressiveness you have on guitar.

You also dropped in a couple of covers on Swept Away, your first solo record – Eight Miles High by The Byrds and Sail On, Sailor by The Beach Boys.

Now people may be thinking “an instrumental cover of a Beach Boys song?” because their songs are all about the voices, the harmonies, the vocal arrangements. But you produced a cracking instrumental version of Sail On, Sailor, which goes back to what I was just saying – there’s a very expressive, melodic tone to your playing.

SH: That’s what I love, I’ve always had a great love of melody. I’m not really a singer – I tried my hand at singing, even on Swept Away, but I hated it (laughs). I did not need to be singing, I just needed to shut up and play! (laughter).

What actually happened was the guitar took over as my voice; I would rather sing with the guitar than just throw a bunch of notes at you. I’m not saying that’s right or wrong, but that’s my choice.

And it’s a song that has always sounded like New York City to me, even though I know that’s not what it’s supposed to be about – it’s supposed to be about the Vietnam War and things that were going on in the late 60’s and early 70’s.

But the production and the arrangement and the way it’s performed, it just feels like Manhattan to me.

I wanted to do a version because I liked the song but, when I listened to it in conjunction with Sunset in Central Park, it just sounded like Manhattan!

RM: That’s really interesting because something I wanted to talk about are the covers on the album, particularly What’s Going On. My first thought on hearing your version was that you had a really perfect fit for the soundscapes you created on the album.

And you’re absolutely right; it feels like it should be on an album about Manhattan, which is extraordinary.

SH: Yeah, and it’s really strange because I know that’s probably not what Marvin Gaye intended.

I don’t even think it was produced or recorded in New York – I think it was recorded in Detroit or L.A.

But the performance, the sound of it and everything about it just sounds like Manhattan to me.

RM: I think also though, and credit where credit’s due, it falls into place because of your skill as a guitarist. That song is quite poignant lyrically, but obviously you are expressing the song instrumentally through your phrasing, tone and touch. And it’s not just the notes you are playing – it’s where you place them.

SH: Why thank you. It’s sometimes a conscious choice and sometimes an unconscious choice, but it’s just the way I’ve learned to play. I learned to play guitar off of B.B. King blues records, basically, and he has such a touch; he has an amazing touch on guitar. And amazing phrasing.

So that’s where I learned just how important phrasing was and how important silence was – the silence between notes is just as important, and sometimes even more important, than the notes themselves.

RM: Absolutely.

SH: So I learned all that from B.B. King, because he has always had this beautiful knack for phrases that sound very vocal; he plays the way he sings, which is really cool.

But so does Albert King and a lot of those early blues guys; I think that is in me by osmosis (laughs).

As I evolved as a player that all just got pulled in; now it’s a major part of my playing.

RM: It’s part of your musical DNA, I would suggest.

SH: Yeah, you’re right.

RM: So, with all that in mind, do you think a twenty-five or thirty year old Steve Hunter could play what you play on The Manhattan Blues Project?

SH: No, I don’t think so. I think there had to be an evolution there and I don’t think I could have played this album when I was twenty-five or thirty, because of where I was then to where I am now.

But as I was saying, the stuff from B.B. King was in there but at twenty, twenty-five and thirty I was still into rock and roll – but it was blues based rock and roll so it was still melody oriented.

It wasn’t always just jamming, although that was a part of it, but over several years it’s been this evolution.

I did try my hand at shredding when shredding became all the rage. I really did, but it just never worked for me or my fingers – I didn’t like it and my fingers just didn’t like it! (laughs). It just didn’t fit me.

I love what those guys can do; when I listen to Joe Satriani or Steve Vai or any of those types of players it’s wonderful, just amazing! But it’s just not me, so I stopped fighting it and said “well, I gotta play the way I play. Whatever comes out, that’s what it is!” (laughs).

RM: You touched there on the talents of Joe Satriani; The Manhattan Blues Project has a very notable list of guest musicians playing on the album including Satriani and Marty Friedman.

Marty and Joe are not exactly slouches when it comes to running fingers up and down a fretboard (laughs), so it must have been quite exciting to have that contrast of your own style then these guys putting down their own licks…

SH: Oh it was amazing! When I wrote the song Twilight in Harlem I said to my wife Karen “it would be great if we could get Satriani to play!”I was actually trying to get Joe and Steve Vai, because they know each other and Steve was a student of Joe’s for a while. So I was trying to get Steve but he was out on the road; when I tried to contact him he was in Russia so I figured that wasn’t going to work (laughs).

Then I asked my friend Jason Becker who he thought would be great to follow Joe and he was the one that thought of Marty Friedman. And when he said Marty’s name I thought “of course!”

I didn’t know Marty that well but Jason does; he was the one that broke the ice between the two of us.

So I contacted Marty and he was into it but, but when I wrote the solos I actually wrote them with Joe Satriani and Steve Vai in mind. But I was a little worried when I wrote those solos because what would happen if neither of them could do it? (laughs).

But I really wanted that contrast between the way I play and the way they play.

RM: Jason Becker's association with Marty goes back to when they played together in the eighties in the heavy metal band Cacophony. But for those that don’t know we should also say that Jason was an extraordinarily talented guitarist until tragically struck down with Motor Neurone Disease, known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease in the United States.

SH: That’s right, ALS, yeah.

RM: His story of survival is absolutely inspirational. And he is still composing?

SH: Yeah, he’s still composing and every once in a while he’ll send me something that he’s working on; he’s still writing the most beautiful stuff. I knew Jason when he was well. We were pals and hung out together in Vancouver when we were working on the David Lee Roth album A Little Ain’t Enough.

We had a great time together but I have eyesight problems so we were making fun of each other’s lameness (laughs). And while that was funny for a time Jason’s health became very serious very quickly and it got to the point where he couldn’t even breathe on his own.

He went through all the anger, all the frustration and the depression, but he worked through all that stuff keeping his great sense of humour the whole time – he and I used to tease each other all the time and just crack each other up. And we still do!

You should read some of the emails we send back and forth – some of them are pretty disgusting (laughter) but they are hilarious! We have such a great time. I love him to death and he’s one of my best friends.

And through all that the music is still in there and he finds ways to get it out.

RM: Fantastic; such an inspiration as regards what can still be achieved, no matter what life throws at you.

I don’t know Jason but from what I’ve read, what he makes of his life and what you have just said it’s clear he’s quite an individual and a wonderful character.

SH: If you ever met him you would never forget him. He’s one of the most incredible human beings on the planet and he inspires me every day. All I have to do is think about my bad eyes and how bad I have it and “oh poor, poor me,” and then I think of Jason and say “what the hell’s the matter with you? There’s nothing wrong with you!”

RM: Yes, it’s such a great leveller. My wife Anne used to work in the Care profession, looking after people with learning difficulties, dementia and physical disabilities.

One particular girl was paraplegic and couldn’t communicate very well but she had a wicked sense of humour and would laugh like a drain at jokes she heard. I would sometimes talk to her for a few minutes, telling jokes, while thinking “I have absolutely no problems worth worrying about.”

SH: I think that’s wonderful; I think that’s really moral. I think we tend to forget that we all have some sort of compromise – there’s always something that we can’t do. Maybe not an affliction, just something we can’t do we wish we could do. I think that’s universal.

So when you see a guy like Jason, whose dream is to make music – and it doesn’t make any difference what the hell gets thrown at him – he still finds a way to make that music.

That just makes it so much easier for everybody else. That’s why he’s such a great inspiration.

RM: And you paid him a nice compliment by recording his short piece Daydream by the Hudson for the album; that’s a lovely little interlude.

SH: That’s a beautiful piece. When I was about at the middle of the album I asked Jason if he had any little musical bits that I could make into something and, if he did, to send some stuff over.

So we got on Skype one day – his nurse can read his eye movements so we can talk back and forth – and we went through about twenty or thirty little pieces of music. I took the ones I thought were pretty cool and stuck them on my desktop.

When I got towards the end of the album I thought “I want to do something with Jason” and I went through all the pieces he had sent me. There was a lot of cool little stuff, but the one that became Daydream by the Hudson just stood out. I did a little editing but nothing serious – I just cut it so it had a nice cadence, put some guitars on it and it’s just this really beautiful piece of music.

RM: It’s a lovely little addition to the album. The other cover on the album is, like What’s Going On, a renowned piece in pop and rock terms – Peter Gabriel’s Solsbury Hill.

You’re revisiting the song of course because you played on the original, but on The Manhattan Blues Project you put your own instrumental take on it.

SH: Now the reason that song’s on the album is a little bit more obscure; a lot of people are going to be thinking “what the hell is Solsbury Hill doing on there?” (laughs).

But the reason it’s on the album is because when we were rehearsing to do Peter’s first ever solo tour, the rehearsals were all in Manhattan. And every time I hear the song it just reminds me of Manhattan; going back and forth from the hotel to the rehearsal, sometimes going out to dinner after rehearsing – just really good memories of Peter and rehearsing to do his tour.

And, yes, plus the fact I did play the acoustic guitar parts on the original; I wanted to kind of revisit those parts on my own album and make it an instrumental song. I think the melody is so cool that it works as an instrumental song, but I was a little concerned at first because Peter writes such brilliant lyrics.

So I was a little worried about not having those lyrics on there but once I started working on it I could see that the melody was strong enough to work by itself – just as a melody.

RM: But that goes back to your own melodic tone, Steve, and that expressiveness you have on guitar.

You also dropped in a couple of covers on Swept Away, your first solo record – Eight Miles High by The Byrds and Sail On, Sailor by The Beach Boys.

Now people may be thinking “an instrumental cover of a Beach Boys song?” because their songs are all about the voices, the harmonies, the vocal arrangements. But you produced a cracking instrumental version of Sail On, Sailor, which goes back to what I was just saying – there’s a very expressive, melodic tone to your playing.

SH: That’s what I love, I’ve always had a great love of melody. I’m not really a singer – I tried my hand at singing, even on Swept Away, but I hated it (laughs). I did not need to be singing, I just needed to shut up and play! (laughter).

What actually happened was the guitar took over as my voice; I would rather sing with the guitar than just throw a bunch of notes at you. I’m not saying that’s right or wrong, but that’s my choice.

The critically acclaimed and predominately instrumental Swept Away contains some of Steve

Hunter's finest melodic improvisations but the outstanding tone, touch and phrasing displayed

on The Manhattan Blues Project is an album a thirty year old Hunter could never have made.

SH: It's also more fun for me to improvise melody; that's something I learned from Kind of Blue by Miles Davis, which is probably one of the greatest albums ever recorded.

What’s wonderful about that album is all the improvisation is very melodic – even from John Coltrane, who at that point in his career was getting more and more abstract.

RM: Yes, quite unexpected.

SH: He just did some beautiful stuff. And Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans… it’s just an extraordinary album for jazz and melodic improvisation and that’s always been kind of my thing.

To improvise a melody, it takes the guitar away from just being a bunch of licks and riffs and makes it more expressive for me, if you know what I mean.

RM: I know exactly what you mean and that particular album, certainly as regards jazz albums, was one of the first records to cross boundaries and genres. And there’s a similarity there with The Manhattan Blues Project because it’s a crossover album, too – blues, pop, rock, instrumental.

You have a crossover commonality with an album like Kind Of Blue but the main thread is clearly melody and the understanding of melody.

SH: I’m not even going to try and hide the fact that Kind Of Blue was a big inspiration on that album, it really was. In fact when Karen and I were talking about the cover artwork, I wanted it to be very close to the Kind Of Blue album cover. It’s one of my all-time favourite albums and there was a lot of inspiration from that album that ended up on The Manhattan Blues Project.

RM: That’s a nice homage to that album and a great idea. Keeping to the thread of favourites and inspirations, on your album Short Stories you did a lovely little version of Flying, the Beatles instrumental.

SH: Yeah and you know, I can’t help it, I’m just a blatant Beatles and George Martin fan! (laughs).

There was a wonderful story on our Public Broadcast System just last night about George Martin and those five guys – the Beatles and George – made some of the most extraordinary music ever.

When you go back and listen to those early albums you can hear that they are just poppy, cute little songs but they were different, we had never heard anything quite like that here in America.

But, boy, when you get around albums like Sgt Pepper, you hear that these guys are geniuses.

We call them aliens (laughs); you can’t write that many great songs, you can’t write album after album of nothing but hit songs. But look at Rubber Soul and Revolver, full of endlessly wonderful songs.

And George Martin’s production has always been an inspiration to me because he and the Beatles – all of them – had tremendously open minds. They were so creative, they would try anything.

RM: I think people – certainly now – recognise George Martin’s place in Beatles history.The way I interpret it is the Beatles in the studio were a five piece.

SH: Yes they were and I think they would admit that too; I think they would say the very same thing. George added so much to what they wanted. A lot of times they would come to him and say something like “George, can you make this sound like it’s underwater?” and they would leave. Then George would think “yeah, I probably can make it sound like it’s underwater” (laughs).

He would experiment and try different things and that’s wonderful – that’s what the creative thing is all about, that’s where you get these extraordinary records.

Throw away the rule books, throw away all that crap and whatever comes to mind give it a try, you know? And they came up with such beautiful stuff. In those days it was so unusual to hear strings on a pop record, so to hear it on something like Eleanor Rigby or Yesterday, just extraordinary.

And George got a sound out of them – and the way he wrote the charts – that was particular to him.

RM: Staying with the Beatles but returning to The Manhattan Blues Project, there’s a very poignant song called Flames of the Dakota about John Lennon’s passing and the flames marked on the wall of the building where he died.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I thought I detected another tribute in there by way of some slide guitar work in the style of George Harrison…

SH: Oh, no question about it; it’s a tribute to both of them. I always thought George was terribly under-rated as a songwriter and a guitar player. He was my favourite Beatle when I was younger, mainly because he was the main guitar player and that’s what I was trying to do.

But also, when I heard some of the songs he wrote, like Taxman? That’s a brilliant song but I didn’t know he had written it until I got the album and saw his name on it.

And then he comes out with Something which, as George Martin said on that programme last night, is probably the most incredible love song ever written. I couldn’t agree with him more, it’s just brilliant.

I started to realise this guy really is a genius. When he does his own albums you really start to hear the genius in his writing and in his skills as a guitar player. So Flames of the Dakota is a tribute to him, too.

RM: Because of the Lennon and McCartney mystique and their creative forces George Harrison tends to slip into third place but I think you’re right, desperately under-rated as a guitar player.

That said, a lot of great guitar players immediately flag up George Harrison as an influence.

SH: I think he played such beautiful slide guitar; he played slide in a way no-one else did.

If you say Duane Allman you hear a blues slide, like on Layla and the Derek and the Dominos record, or on the first couple of Allman Brothers albums. But if you say George Harrison, you get this very distinct genre of slide guitar. He worked out these wonderful, gorgeous melodies – sometimes they would be doubled, sometimes they would be in harmony – and he would get this sound on it that was different to everybody else.

RM: From the contrast of that George Harrison style and the poignancy of Flames of the Dakota to a fun blues boogie and The Brooklyn Shuffle, featuring guest guitarists Johnny Depp and Joe Perry.

For an actor, Johnny Depp isn’t too sloppy on a guitar, but joking aside he's not half bad on a six-string…

SH: Oh he’s a good player, but he kind of started out as a musician. The story I heard about him is he came to L.A. with a band and they were trying to get a record deal. I never got to see them live but they were a band called The Kids and they just never got a deal; it never happened.

Anyway, next thing you know Johnny’s found himself acting to make a living and the rest is history.

He’s turned into this incredible actor but he’s a great guitar player, he really is.

We played with him at The 100 Club in London and he was amazing; I really enjoyed playing with him.

RM: I’ve never seen Johnny Depp play live but I’ve seen clips on YouTube and heard audio; everyone does say he could hold his own on stage if he ever wanted to make a go of it.

SH: Oh yeah, no question about it. If he wanted to put a band together and go out and play he could do it without any problem.

RM: And I don't think he would have any problem getting a deal this time...

Hunter's finest melodic improvisations but the outstanding tone, touch and phrasing displayed

on The Manhattan Blues Project is an album a thirty year old Hunter could never have made.

SH: It's also more fun for me to improvise melody; that's something I learned from Kind of Blue by Miles Davis, which is probably one of the greatest albums ever recorded.

What’s wonderful about that album is all the improvisation is very melodic – even from John Coltrane, who at that point in his career was getting more and more abstract.

RM: Yes, quite unexpected.

SH: He just did some beautiful stuff. And Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans… it’s just an extraordinary album for jazz and melodic improvisation and that’s always been kind of my thing.

To improvise a melody, it takes the guitar away from just being a bunch of licks and riffs and makes it more expressive for me, if you know what I mean.

RM: I know exactly what you mean and that particular album, certainly as regards jazz albums, was one of the first records to cross boundaries and genres. And there’s a similarity there with The Manhattan Blues Project because it’s a crossover album, too – blues, pop, rock, instrumental.

You have a crossover commonality with an album like Kind Of Blue but the main thread is clearly melody and the understanding of melody.

SH: I’m not even going to try and hide the fact that Kind Of Blue was a big inspiration on that album, it really was. In fact when Karen and I were talking about the cover artwork, I wanted it to be very close to the Kind Of Blue album cover. It’s one of my all-time favourite albums and there was a lot of inspiration from that album that ended up on The Manhattan Blues Project.

RM: That’s a nice homage to that album and a great idea. Keeping to the thread of favourites and inspirations, on your album Short Stories you did a lovely little version of Flying, the Beatles instrumental.

SH: Yeah and you know, I can’t help it, I’m just a blatant Beatles and George Martin fan! (laughs).

There was a wonderful story on our Public Broadcast System just last night about George Martin and those five guys – the Beatles and George – made some of the most extraordinary music ever.

When you go back and listen to those early albums you can hear that they are just poppy, cute little songs but they were different, we had never heard anything quite like that here in America.

But, boy, when you get around albums like Sgt Pepper, you hear that these guys are geniuses.

We call them aliens (laughs); you can’t write that many great songs, you can’t write album after album of nothing but hit songs. But look at Rubber Soul and Revolver, full of endlessly wonderful songs.

And George Martin’s production has always been an inspiration to me because he and the Beatles – all of them – had tremendously open minds. They were so creative, they would try anything.

RM: I think people – certainly now – recognise George Martin’s place in Beatles history.The way I interpret it is the Beatles in the studio were a five piece.

SH: Yes they were and I think they would admit that too; I think they would say the very same thing. George added so much to what they wanted. A lot of times they would come to him and say something like “George, can you make this sound like it’s underwater?” and they would leave. Then George would think “yeah, I probably can make it sound like it’s underwater” (laughs).

He would experiment and try different things and that’s wonderful – that’s what the creative thing is all about, that’s where you get these extraordinary records.

Throw away the rule books, throw away all that crap and whatever comes to mind give it a try, you know? And they came up with such beautiful stuff. In those days it was so unusual to hear strings on a pop record, so to hear it on something like Eleanor Rigby or Yesterday, just extraordinary.

And George got a sound out of them – and the way he wrote the charts – that was particular to him.

RM: Staying with the Beatles but returning to The Manhattan Blues Project, there’s a very poignant song called Flames of the Dakota about John Lennon’s passing and the flames marked on the wall of the building where he died.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I thought I detected another tribute in there by way of some slide guitar work in the style of George Harrison…

SH: Oh, no question about it; it’s a tribute to both of them. I always thought George was terribly under-rated as a songwriter and a guitar player. He was my favourite Beatle when I was younger, mainly because he was the main guitar player and that’s what I was trying to do.

But also, when I heard some of the songs he wrote, like Taxman? That’s a brilliant song but I didn’t know he had written it until I got the album and saw his name on it.

And then he comes out with Something which, as George Martin said on that programme last night, is probably the most incredible love song ever written. I couldn’t agree with him more, it’s just brilliant.

I started to realise this guy really is a genius. When he does his own albums you really start to hear the genius in his writing and in his skills as a guitar player. So Flames of the Dakota is a tribute to him, too.

RM: Because of the Lennon and McCartney mystique and their creative forces George Harrison tends to slip into third place but I think you’re right, desperately under-rated as a guitar player.

That said, a lot of great guitar players immediately flag up George Harrison as an influence.

SH: I think he played such beautiful slide guitar; he played slide in a way no-one else did.

If you say Duane Allman you hear a blues slide, like on Layla and the Derek and the Dominos record, or on the first couple of Allman Brothers albums. But if you say George Harrison, you get this very distinct genre of slide guitar. He worked out these wonderful, gorgeous melodies – sometimes they would be doubled, sometimes they would be in harmony – and he would get this sound on it that was different to everybody else.

RM: From the contrast of that George Harrison style and the poignancy of Flames of the Dakota to a fun blues boogie and The Brooklyn Shuffle, featuring guest guitarists Johnny Depp and Joe Perry.

For an actor, Johnny Depp isn’t too sloppy on a guitar, but joking aside he's not half bad on a six-string…

SH: Oh he’s a good player, but he kind of started out as a musician. The story I heard about him is he came to L.A. with a band and they were trying to get a record deal. I never got to see them live but they were a band called The Kids and they just never got a deal; it never happened.

Anyway, next thing you know Johnny’s found himself acting to make a living and the rest is history.

He’s turned into this incredible actor but he’s a great guitar player, he really is.

We played with him at The 100 Club in London and he was amazing; I really enjoyed playing with him.

RM: I’ve never seen Johnny Depp play live but I’ve seen clips on YouTube and heard audio; everyone does say he could hold his own on stage if he ever wanted to make a go of it.

SH: Oh yeah, no question about it. If he wanted to put a band together and go out and play he could do it without any problem.

RM: And I don't think he would have any problem getting a deal this time...

RM: Then there's Joe Perry, returning the guest spot compliment albeit some forty years later (laughs).

I am of course referring to you playing on Aerosmith’s cover of Train Kept A-Rollin’ back in the day, but that leads to a whole other topic that would take us a day to get through – your prolific session and guest work from that Aerosmith session to more recent, credited guest spots such as with Glen Campbell.

SH: Yes, that’s right.

RM: But a number of those early sessions and recordings were uncredited – was that an issue for you, or just what happened back in the day?

SH: Well it was kind of just the way things were being done then. I know there was a controversy within the labels – I heard this second and third-hand so I didn’t know if it was completely true or not – but I heard a lot of labels were getting very angry about putting bands they had signed in to the studio while the producers would get other guitar players or drummers or bass players to come in and do the sessions.

The label would say “Why can’t you use the band? They’re the ones that will be going out on the road, why use other players?” And some producers would say “Because these players are better players!”

So there were are a lot of labels getting very angry about that and they were saying things like “We’ll pull the plug if you do that. If this band can’t cut it we’re going to drop them!” It was getting really ugly.

So during those times there were a lot sessions with a lot of guitar players, drummers, bass players, keyboard players – even singers – doing stuff that wasn’t credited. And when you interview a few years later you’re hesitant to say anything because there’s no proof that you played! (laughs).

Except when people know your style of playing – Dick Wagner and I did a lot of that stuff and our styles and backgrounds are similar but not exactly the same, so you can hear the difference between us.

If you’ve listened to some of the things we did with Alice Cooper and Lou Reed, you can hear the difference in our playing; it’s pretty obvious.

But, yeah, it does kind of bum you out that you don’t get credit, because I’m the guy that’s going in and doing all the work. You just have to hope that when people hear it they can figure it out and say “That sounds like Steve!” or “That sounds like Dick!” And eventually that did start happening.

I never mentioned a thing about Train Kept A-Rollin’ until years later and somebody asked me in an interview if that was me. I said “Yep, I played the first half and Dick played the second half!” and then the cat was out of the bag! (laughter).

I know it probably seems a little weird to have an album where there are all these players, but the thing is an album is a piece of work that’s cut in stone; once it’s out you can’t go back and change it.

You want to make absolutely the best record you can, because it’s going to be heard over and over again.

But when you see a live show it has all these variables and I don’t care how much you try to do a show the exact same way every night, there’s always some variation.

But in those days nobody tried to do that, it was looser, a lot of improvisation; the album would take on a new meaning when the songs were played live.

I don’t think people went to a show and thought “I wish Steve was up there playing this song!” I don’t think people thought that way or thought they were getting ripped off (laughs) – but I think they would play the album and say “Wow, I really loved that Train Kept A-Rollin’” because it was a great version by Aerosmith.

But when they play it live I think they do a slight variation of it – I’ve never seen them do it but I’ve seen videos and I think they kind of stuck more to The Yardbirds version?

RM: Yes and they used to perform a slower version, too.

SH: And it sounded great, it really sounded cool. But it’s such a touchy, tricky thing; you’re kind of stuck in the middle. You’re trying to push your own career along and trying to get credit for things you’ve done, yet on the other hand you have to respect the wishes of the producer and what the band’s trying to do.

It’s a real delicate balance.

RM: Well, where things have gone in your favour, credit wise, is the resurgence in classic rock and the current age of reissues, anniversary releases, remasters and remixed for surround sound albums.

When these products come out everything and everyone is credited; new booklets come out with who played on what and where. So people like you and Dick start to get the recognition and credit you’re due.

But it’s astonishing it has taken so long.

SH: It is, but it was just the way work was done in those days. But it is nice having these things come out and we finally get credit – and it’s kind of cool that we can do interviews and set the record straight as to who played what. Well, as long as we can remember (laughs), because the problem is songs like Train Kept A-Rollin’ were done forty years ago; it’s a little tough to remember exactly what happened.

And some of the stuff with Alice Cooper – we did a lot of recording in those days so it’s a little tough sometimes to remember exactly what rhythm part I played where.

But on the solos I think you can hear the difference between Dick and me, or me and somebody else, or Dick and somebody else... you pick up a style just like a vocal style and you can hear the difference.

RM: And around that time you and Dick started to strike up a really solid partnership. There was clearly a complimentary aspect to your playing but with that contrast of styles. You mentioned Alice there – you and Dick played on the classic Alice Cooper band album Billion Dollar Babies.

SH: That’s right, yeah.

RM: Then you both played with Lou Reed for a couple of years and recorded the Berlin album.

Now that opens up another uncredited can of worms – the live version of Sweet Jane gained a new lease of life beyond the Velvet Underground original with an extended intro, which you came up with.

SH: Yes, but actually I do have credit for that on the live album; and a couple of the reissued CD’s you’ll see “Intro by Steve Hunter.” So they did credit me but I didn’t make any money off of it – that’s the can of worms that we’ve been working on for nearly forty years (laughs).

But part of that was just my ignorance of publishing and me being a young and naive snot-nosed kid who didn’t know what was going on (laughter). So it was my own fault but that intro to Sweet Jane, I did write that and it opened up so many doors for me, right from the time that it was released.

I wasn’t allowed to make money on it (laughs) but it sure helped my career a lot!

RM: And that goes back to what we were saying earlier about perspective; looking at things around you and realising in the great scheme of things we’ve actually doing OK.

You look at that version of Sweet Jane – which has become the definitive live recording – and acknowledge what it did for your career.

And Aerosmith’s version of Train Kept A-Rollin’ is held in such high esteem; a truly classic cover.

Did your time with Lou just run its course, or were things such as the royalty issues part of the reason you and Dick joined Alice Cooper in 1975?

SH: Well, when I think about it, it just seemed like the natural thing to do.

I had gone over to London and recorded most of the guitars for the Berlin album and there was also this wonderful acoustic guitar player from Toronto, name of Gene Martynec, who played some of the most beautiful acoustic guitars on songs like The Bed; just beautiful stuff.

And if I remember right I think Dick played on Sad Song, but Dick did a lot of the background singing on Berlin because he has a great voice. Then we did Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal and Lou Reed Live but it just seemed like the next thing, or natural progression, was to play with Alice Cooper.

We never got fired or anything, we just moved on – and I think Lou just moved on. Because I know how Lou is; he’s very creative and doesn’t like to stay in one area too long – it gets boring for him.

So it was never going to be a case of him having the same band for any real length of time, he would just like to change things and add new influences. There was a time I worked with him where he had a cello player; sometimes he goes out and doesn’t have a drummer.

I respect that; that’s a really cool way to keep your stuff fresh and to keep your shows fresh.

That’s what’s sustained him so long and I think that’s commendable.

RM: The Lou Reed’s of the world are continually reinventing themselves. Funnily enough, just a year or so prior to you and Lou Reed moving on, Bowie was doing the same thing with The Spiders From Mars.

You think about the success he had with that particular band but at the peak of their success he retired his Ziggy persona, walked away from The Spiders and completely reinvented himself.

But that’s how some of the truly creative artists – Reed, Bowie, Todd Rundgren et al – work and succeed.

SH: Yes, but in those days I didn’t think of myself as an artist, I thought of myself as a guitar player.

I loved being a sideman and doing sessions, I really loved it. But I didn’t like, and wasn’t cut out to do, the jingles and stuff like that. I tried doing that but I was just no good at it. I can’t read a chart that well and I can’t play five notes four hundred thousand different ways (laughs), so I never got on well doing jingles. Which is too bad, because it’s a great way to make a living and you get to meet a lot of great musicians, engineers and producers. But, as I said, I just wasn’t very good at it.

Doing album sessions though, that was a joy; but I didn’t like to stay in one place too long either.

Not so much because I would get stale but because I wanted to kick myself along a little further, to make it to that next notch. I was afraid if I stayed too long in any one band I would get locked in to something and I wouldn’t evolve as a player.

And that was really important to me – I wanted to evolve, keep learning and get better at what I was trying to do. So I liked moving from artist to artist, from album to album, I really liked that.

RM: And at that particular time, as regards studio creativity and live performance, you and Dick couldn’t have made a much better choice than Alice Cooper. You arrived at the time of Welcome to My Nightmare and were part of the subsequent Goes to Hell period and the theatrical rock and roll Alice was creating on stage.

SH: Yeah and the thing is I was very much into the Alice Cooper theatre stuff.

I wasn’t at first – I didn’t get it at first – but I was really good friends with the original Alice Cooper group, I knew all those guys really well. They lived in Detroit at the time and I actually knew them before I’m Eighteen was a hit single, so we were all really good friends.

But I really didn’t get what they were doing. I thought “well this is kind of silly, can’t you just get up there and rock and roll like the Stones do?” (laughs).

And then I saw them one time – they were on the Billion Dollar Babies tour, they had got me tickets and we hung out backstage – and the show just blew me away; suddenly I just got it.

And so now I’m thinking “Oh man, I would love to do that!” (laughter). And it was so weird that a year after I saw them I was doing that, including on the same stage I had seen them on!

It was bizarre, almost like I had a premonition or something; but I loved the theatrical part of rock and roll.

RM: And nobody did it quite like Alice, especially at that time in his career.

If you had a premonition back then, you certainly had musical déjà vu in 2011 when you guested on the Bob Ezrin produced sequel Welcome 2 My Nightmare. The first track on that album, I Am Made Of You, is quite an opening statement and Alice went on to comment that your solo on that song is the best solo on any of his records. That has to be quite gratifying…

SH: Oh it’s very gratifying and listen, let me tell you, we worked hard on that solo because I knew as soon as I heard the song that the solo had to be a real statement.

The problem was it couldn’t overstate the vocal melody yet it couldn’t be understated – it had to be powerful because it’s a very powerful song.

It was a very delicate, special kind of balance to make that solo work, so we worked on it pretty hard.

And by “work on it” I mean I went in and recorded it several times until we started honing in on what we wanted. I think there is only one punch on the whole solo – I just made a little boo-boo and I had to fix it – because we could see right away that the solo had to have cohesion.

The punch we did was where I misthreaded something and I had to fix that, but the solo from start to finish is one pass, which was very important for the song...

I am of course referring to you playing on Aerosmith’s cover of Train Kept A-Rollin’ back in the day, but that leads to a whole other topic that would take us a day to get through – your prolific session and guest work from that Aerosmith session to more recent, credited guest spots such as with Glen Campbell.

SH: Yes, that’s right.

RM: But a number of those early sessions and recordings were uncredited – was that an issue for you, or just what happened back in the day?

SH: Well it was kind of just the way things were being done then. I know there was a controversy within the labels – I heard this second and third-hand so I didn’t know if it was completely true or not – but I heard a lot of labels were getting very angry about putting bands they had signed in to the studio while the producers would get other guitar players or drummers or bass players to come in and do the sessions.

The label would say “Why can’t you use the band? They’re the ones that will be going out on the road, why use other players?” And some producers would say “Because these players are better players!”

So there were are a lot of labels getting very angry about that and they were saying things like “We’ll pull the plug if you do that. If this band can’t cut it we’re going to drop them!” It was getting really ugly.

So during those times there were a lot sessions with a lot of guitar players, drummers, bass players, keyboard players – even singers – doing stuff that wasn’t credited. And when you interview a few years later you’re hesitant to say anything because there’s no proof that you played! (laughs).

Except when people know your style of playing – Dick Wagner and I did a lot of that stuff and our styles and backgrounds are similar but not exactly the same, so you can hear the difference between us.

If you’ve listened to some of the things we did with Alice Cooper and Lou Reed, you can hear the difference in our playing; it’s pretty obvious.

But, yeah, it does kind of bum you out that you don’t get credit, because I’m the guy that’s going in and doing all the work. You just have to hope that when people hear it they can figure it out and say “That sounds like Steve!” or “That sounds like Dick!” And eventually that did start happening.

I never mentioned a thing about Train Kept A-Rollin’ until years later and somebody asked me in an interview if that was me. I said “Yep, I played the first half and Dick played the second half!” and then the cat was out of the bag! (laughter).

I know it probably seems a little weird to have an album where there are all these players, but the thing is an album is a piece of work that’s cut in stone; once it’s out you can’t go back and change it.

You want to make absolutely the best record you can, because it’s going to be heard over and over again.

But when you see a live show it has all these variables and I don’t care how much you try to do a show the exact same way every night, there’s always some variation.

But in those days nobody tried to do that, it was looser, a lot of improvisation; the album would take on a new meaning when the songs were played live.

I don’t think people went to a show and thought “I wish Steve was up there playing this song!” I don’t think people thought that way or thought they were getting ripped off (laughs) – but I think they would play the album and say “Wow, I really loved that Train Kept A-Rollin’” because it was a great version by Aerosmith.

But when they play it live I think they do a slight variation of it – I’ve never seen them do it but I’ve seen videos and I think they kind of stuck more to The Yardbirds version?

RM: Yes and they used to perform a slower version, too.

SH: And it sounded great, it really sounded cool. But it’s such a touchy, tricky thing; you’re kind of stuck in the middle. You’re trying to push your own career along and trying to get credit for things you’ve done, yet on the other hand you have to respect the wishes of the producer and what the band’s trying to do.

It’s a real delicate balance.

RM: Well, where things have gone in your favour, credit wise, is the resurgence in classic rock and the current age of reissues, anniversary releases, remasters and remixed for surround sound albums.

When these products come out everything and everyone is credited; new booklets come out with who played on what and where. So people like you and Dick start to get the recognition and credit you’re due.

But it’s astonishing it has taken so long.

SH: It is, but it was just the way work was done in those days. But it is nice having these things come out and we finally get credit – and it’s kind of cool that we can do interviews and set the record straight as to who played what. Well, as long as we can remember (laughs), because the problem is songs like Train Kept A-Rollin’ were done forty years ago; it’s a little tough to remember exactly what happened.

And some of the stuff with Alice Cooper – we did a lot of recording in those days so it’s a little tough sometimes to remember exactly what rhythm part I played where.

But on the solos I think you can hear the difference between Dick and me, or me and somebody else, or Dick and somebody else... you pick up a style just like a vocal style and you can hear the difference.

RM: And around that time you and Dick started to strike up a really solid partnership. There was clearly a complimentary aspect to your playing but with that contrast of styles. You mentioned Alice there – you and Dick played on the classic Alice Cooper band album Billion Dollar Babies.

SH: That’s right, yeah.

RM: Then you both played with Lou Reed for a couple of years and recorded the Berlin album.

Now that opens up another uncredited can of worms – the live version of Sweet Jane gained a new lease of life beyond the Velvet Underground original with an extended intro, which you came up with.

SH: Yes, but actually I do have credit for that on the live album; and a couple of the reissued CD’s you’ll see “Intro by Steve Hunter.” So they did credit me but I didn’t make any money off of it – that’s the can of worms that we’ve been working on for nearly forty years (laughs).

But part of that was just my ignorance of publishing and me being a young and naive snot-nosed kid who didn’t know what was going on (laughter). So it was my own fault but that intro to Sweet Jane, I did write that and it opened up so many doors for me, right from the time that it was released.

I wasn’t allowed to make money on it (laughs) but it sure helped my career a lot!

RM: And that goes back to what we were saying earlier about perspective; looking at things around you and realising in the great scheme of things we’ve actually doing OK.

You look at that version of Sweet Jane – which has become the definitive live recording – and acknowledge what it did for your career.

And Aerosmith’s version of Train Kept A-Rollin’ is held in such high esteem; a truly classic cover.

Did your time with Lou just run its course, or were things such as the royalty issues part of the reason you and Dick joined Alice Cooper in 1975?

SH: Well, when I think about it, it just seemed like the natural thing to do.

I had gone over to London and recorded most of the guitars for the Berlin album and there was also this wonderful acoustic guitar player from Toronto, name of Gene Martynec, who played some of the most beautiful acoustic guitars on songs like The Bed; just beautiful stuff.

And if I remember right I think Dick played on Sad Song, but Dick did a lot of the background singing on Berlin because he has a great voice. Then we did Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal and Lou Reed Live but it just seemed like the next thing, or natural progression, was to play with Alice Cooper.

We never got fired or anything, we just moved on – and I think Lou just moved on. Because I know how Lou is; he’s very creative and doesn’t like to stay in one area too long – it gets boring for him.

So it was never going to be a case of him having the same band for any real length of time, he would just like to change things and add new influences. There was a time I worked with him where he had a cello player; sometimes he goes out and doesn’t have a drummer.

I respect that; that’s a really cool way to keep your stuff fresh and to keep your shows fresh.

That’s what’s sustained him so long and I think that’s commendable.

RM: The Lou Reed’s of the world are continually reinventing themselves. Funnily enough, just a year or so prior to you and Lou Reed moving on, Bowie was doing the same thing with The Spiders From Mars.

You think about the success he had with that particular band but at the peak of their success he retired his Ziggy persona, walked away from The Spiders and completely reinvented himself.

But that’s how some of the truly creative artists – Reed, Bowie, Todd Rundgren et al – work and succeed.

SH: Yes, but in those days I didn’t think of myself as an artist, I thought of myself as a guitar player.

I loved being a sideman and doing sessions, I really loved it. But I didn’t like, and wasn’t cut out to do, the jingles and stuff like that. I tried doing that but I was just no good at it. I can’t read a chart that well and I can’t play five notes four hundred thousand different ways (laughs), so I never got on well doing jingles. Which is too bad, because it’s a great way to make a living and you get to meet a lot of great musicians, engineers and producers. But, as I said, I just wasn’t very good at it.

Doing album sessions though, that was a joy; but I didn’t like to stay in one place too long either.

Not so much because I would get stale but because I wanted to kick myself along a little further, to make it to that next notch. I was afraid if I stayed too long in any one band I would get locked in to something and I wouldn’t evolve as a player.

And that was really important to me – I wanted to evolve, keep learning and get better at what I was trying to do. So I liked moving from artist to artist, from album to album, I really liked that.

RM: And at that particular time, as regards studio creativity and live performance, you and Dick couldn’t have made a much better choice than Alice Cooper. You arrived at the time of Welcome to My Nightmare and were part of the subsequent Goes to Hell period and the theatrical rock and roll Alice was creating on stage.

SH: Yeah and the thing is I was very much into the Alice Cooper theatre stuff.

I wasn’t at first – I didn’t get it at first – but I was really good friends with the original Alice Cooper group, I knew all those guys really well. They lived in Detroit at the time and I actually knew them before I’m Eighteen was a hit single, so we were all really good friends.

But I really didn’t get what they were doing. I thought “well this is kind of silly, can’t you just get up there and rock and roll like the Stones do?” (laughs).

And then I saw them one time – they were on the Billion Dollar Babies tour, they had got me tickets and we hung out backstage – and the show just blew me away; suddenly I just got it.

And so now I’m thinking “Oh man, I would love to do that!” (laughter). And it was so weird that a year after I saw them I was doing that, including on the same stage I had seen them on!

It was bizarre, almost like I had a premonition or something; but I loved the theatrical part of rock and roll.

RM: And nobody did it quite like Alice, especially at that time in his career.

If you had a premonition back then, you certainly had musical déjà vu in 2011 when you guested on the Bob Ezrin produced sequel Welcome 2 My Nightmare. The first track on that album, I Am Made Of You, is quite an opening statement and Alice went on to comment that your solo on that song is the best solo on any of his records. That has to be quite gratifying…

SH: Oh it’s very gratifying and listen, let me tell you, we worked hard on that solo because I knew as soon as I heard the song that the solo had to be a real statement.

The problem was it couldn’t overstate the vocal melody yet it couldn’t be understated – it had to be powerful because it’s a very powerful song.

It was a very delicate, special kind of balance to make that solo work, so we worked on it pretty hard.

And by “work on it” I mean I went in and recorded it several times until we started honing in on what we wanted. I think there is only one punch on the whole solo – I just made a little boo-boo and I had to fix it – because we could see right away that the solo had to have cohesion.

The punch we did was where I misthreaded something and I had to fix that, but the solo from start to finish is one pass, which was very important for the song...

SH: We got such a beautiful sound on that solo, too. I used one of Bob Ezrin’s Les Paul’s that just sounded wonderful – and once you get that sound right for me, I’m off! (laughs).

I have a tendency to play with what I’m hearing, so if I’m not getting a particularly great sound then unfortunately I don’t think I play very well.

RM: Really? That’s interesting…

SH: Yeah, because I’m fighting the sound all the time. But if you get a really great tone, then it’s like you can just play anything and it sounds fabulous – you just want to play all day, you know?

And when we finally got that solo, we knew it – I mean just knew it – “This is the one.”

RM: I do a Feature Review every month or so and Welcome 2 My Nightmare was a 2011 Feature Review. It’s Alice’s best album in decades but the thing that made me sit up and pay attention was the impact of I Am Made Of You and the solo. To such an extent I actually stopped and played the song again before I let the album run through, which emphasises your point about getting the dramatic statement you wanted.

SH: Yeah, I think Alice and Bob knew if you are going to call an album Welcome 2 My Nightmare it’s got to be a good album and it’s got to have great songs on it. And it’s going to need great production and great performances. So we worked hard on that album to make it say what we wanted it to say.

I think it’s a good album, too – I’m very proud of it and very happy I got to play on it.

RM: And so nice there’s a nod to the remaining members of the original band – and Dick and yourself – who all got to play on it. You also went on tour with Alice in 2011 to promote the album before coming off the road in 2012 to start working on what became The Manhattan Blues Project.

SH: Yes I did and I’ll tell you – that 2011 tour really kicked my butt! (laughs).

It was a seven month long tour and listen, when you get on stage it’s a blast, it’s always a blast, even when you play places where you’re thinking “Are these people really going to get this?” (laughter).

But that’s kind of fun, it’s “Well, we’re going to make them get it!” (laughs). But, the travelling and all that goes with it, at my age? It was really starting to beat me up.

Alice has been doing it his whole life so he’s kind of a road dog – it’s built into him that he can do that – but I hadn’t toured like that in a long time. This was seven straight months and my body just didn’t like it.

And all the time I was out on the road with Alice, during all the travelling and stuff, I was thinking about this album; thinking about what I wanted to do with it, how I wanted to do it and what I wanted to say.

It was constantly at the back of my mind, nagging at me (laughs), so I was always thinking “When I get off this tour Karen and I are going to stay home and we’re going to work on this album.”

And it really was the best thing I could have done because it just felt wonderful, once I dived in to it.

In fact it was just like having a baby; it was kind of sad when it was over! (laughs).

RM: That’s a nice tie-in because we started by talking about the photograph that became the kick-starter for the album and as we head towards the conclusion of our conversation we should talk about the Kickstarter campaign that helped complete it.

You are not the first and will not be the last musician to use an on-line crowd-funding campaign to assist in completing an album, but sometimes it pisses me off when artists, who have the acclaim of their peers or have produced a significant even influential body of work in the past, have to go through this.

Now, fantastic that the fans got behind the Kickstarter campaign and the album project, but I would be interested to hear your own thoughts on this…

SH: That’s a really good question because it is a strange situation, but doing what I do made me fall through some cracks. If I was a singer-songwriter, getting a record deal would just be a matter of whether I had the personality the label’s looking for or if I had the right songs.

But, when you’re an instrumentalist, right away you lose about ninety percent of the labels – “Oh, we don’t know what to do with a guitar player!”

So there you go, now you only have about ten percent of them left and around eight percent of those are looking for shredders!

I have a tendency to play with what I’m hearing, so if I’m not getting a particularly great sound then unfortunately I don’t think I play very well.

RM: Really? That’s interesting…

SH: Yeah, because I’m fighting the sound all the time. But if you get a really great tone, then it’s like you can just play anything and it sounds fabulous – you just want to play all day, you know?

And when we finally got that solo, we knew it – I mean just knew it – “This is the one.”

RM: I do a Feature Review every month or so and Welcome 2 My Nightmare was a 2011 Feature Review. It’s Alice’s best album in decades but the thing that made me sit up and pay attention was the impact of I Am Made Of You and the solo. To such an extent I actually stopped and played the song again before I let the album run through, which emphasises your point about getting the dramatic statement you wanted.

SH: Yeah, I think Alice and Bob knew if you are going to call an album Welcome 2 My Nightmare it’s got to be a good album and it’s got to have great songs on it. And it’s going to need great production and great performances. So we worked hard on that album to make it say what we wanted it to say.

I think it’s a good album, too – I’m very proud of it and very happy I got to play on it.

RM: And so nice there’s a nod to the remaining members of the original band – and Dick and yourself – who all got to play on it. You also went on tour with Alice in 2011 to promote the album before coming off the road in 2012 to start working on what became The Manhattan Blues Project.

SH: Yes I did and I’ll tell you – that 2011 tour really kicked my butt! (laughs).

It was a seven month long tour and listen, when you get on stage it’s a blast, it’s always a blast, even when you play places where you’re thinking “Are these people really going to get this?” (laughter).

But that’s kind of fun, it’s “Well, we’re going to make them get it!” (laughs). But, the travelling and all that goes with it, at my age? It was really starting to beat me up.

Alice has been doing it his whole life so he’s kind of a road dog – it’s built into him that he can do that – but I hadn’t toured like that in a long time. This was seven straight months and my body just didn’t like it.

And all the time I was out on the road with Alice, during all the travelling and stuff, I was thinking about this album; thinking about what I wanted to do with it, how I wanted to do it and what I wanted to say.

It was constantly at the back of my mind, nagging at me (laughs), so I was always thinking “When I get off this tour Karen and I are going to stay home and we’re going to work on this album.”

And it really was the best thing I could have done because it just felt wonderful, once I dived in to it.

In fact it was just like having a baby; it was kind of sad when it was over! (laughs).

RM: That’s a nice tie-in because we started by talking about the photograph that became the kick-starter for the album and as we head towards the conclusion of our conversation we should talk about the Kickstarter campaign that helped complete it.

You are not the first and will not be the last musician to use an on-line crowd-funding campaign to assist in completing an album, but sometimes it pisses me off when artists, who have the acclaim of their peers or have produced a significant even influential body of work in the past, have to go through this.

Now, fantastic that the fans got behind the Kickstarter campaign and the album project, but I would be interested to hear your own thoughts on this…

SH: That’s a really good question because it is a strange situation, but doing what I do made me fall through some cracks. If I was a singer-songwriter, getting a record deal would just be a matter of whether I had the personality the label’s looking for or if I had the right songs.

But, when you’re an instrumentalist, right away you lose about ninety percent of the labels – “Oh, we don’t know what to do with a guitar player!”

So there you go, now you only have about ten percent of them left and around eight percent of those are looking for shredders!

RM: Yes, that's quite true.

SH: Yeah, that’s the hot thing right now and there are a lot of really good players out there.

So that leaves two percent and most of those labels were so small they really couldn’t afford to have a bunch of artists.

And that two percent are saying “Well, we’d really like to sign you but we don’t have enough money to give you a budget” so pretty soon you’re saying “All right, I’ll do it myself!”

And thank God for Kickstarter, otherwise we probably wouldn’t have had this album out – or at least not in the shape it’s in. Kickstarter worked for me – really worked for me – and the fans did get behind it.

And I’m still thanking them because it felt like a team effort, but this time I didn’t know the people in the team until they came in with their names, made their pledges and we sent emails back and forth.

I’ve made some really good friends through Kickstarter and I was very, very happy at the response we got.

And they’re still supporting me – they Tweet the album, they post about the album, they share their thoughts on the album… it’s really wonderful.