From Acolyte to Wolflight...

Muirsical Conversation with Steve Hackett

Muirsical Conversation with Steve Hackett

For fans of Steve Hackett and classic era Genesis this is a win-win period.

Steve Hackett’s previous album of all-new material, 2011s Beyond the Shrouded Horizon, was an excellent mix of musical vignettes and larger rock-meets-orchestra pieces.

Beyond the Shrouded Horizon was followed by Genesis Revisited II, the Revisited II Selection album and the highly successful Genesis Revisited tour shows.

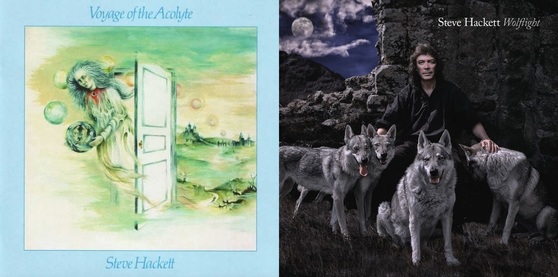

In 2015, four decades on from his debut solo album Voyage of the Acolyte and a subsequent body of work that includes progressive, world music, instrumental and classical genre releases, Steve Hackett celebrated his 40th Anniversary as a solo artist by bathing in the Wolflight of another Top 40 album success and his most accomplished and striking work to date.

2015 is also a year destined to be one of the noted guitarist’s best.

Following the release of Wolflight and the album's deserved critical acclaim came the announcement of Autumn dates in Europe and the UK (with follow-on US dates) that will celebrate the Acolyte to Wolflight 40th Anniversary and dip back in to the Genesis back catalogue that featured Steve Hackett when the band were at the peak of their progressive powers.

However anyone looking for anecdotes about lambs lying down or tricks of a particular tail will have to look elsewhere – the Muirsical Conversation that follows concentrated on Steve Hackett’s solo career with specific emphasis on Wolflight, an album that has as interesting a story attached to its origins as it has outstanding musical stories within…

Ross Muir: Wolflight is both delicate and complex in construction with a lot of light and shade.

Well arranged harmonies and melody lines mesh with folk, world music, heavy rock and even a little blues to produce an album that's almost operatic in scope – and that’s before we even look at the lyrical themes.

How did you conceive and develop Wolflight and come up with such a concept?

Steve Hackett: Well first of all the title derives from an article my wife Jo did some years back; it might even be as much as ten years ago now. Jo wrote an article for a magazine which talked about the Wolflight, the hour just before the dawn when wolves start to hunt.

Now, as far as we know, the earliest references to Wolflight in literature is in the Odyssey – Homer referring to Odysseus when he wakes up in the Wolflight – but while the references are that old we found not that many people had heard of the concept. So that formed the basic idea for the album, which we started to write between us – and the darkness-to-light hour of the Wolflight just seemed to be the perfect title for it.

Then photographer friends of ours, Maurizio and Angéla Vicedomini, who have been doing album covers for us recently, discovered a guy who was raising wolves in a place about one hour outside of Rome.

Maurizio and Angéla said we could possibly meet up with this guy and his wife to take photos of the wolves, so we went out there and spent a day doing just that… and that’s just the outer wrappings of the album and the title track!

RM: Pretty impressive wrappings and I so envy you that time with the wolves. And the lyrical themes?

SH: Well, another reason we were drawn to the idea of Wolflight as a title was that we were writing a song about early peoples; the nomadic tribes who took on the Chinese – the ones for whom the Great Wall of China was built to keep them out – and the people who eventually over-ran the Roman Empire and brought down the Romans.

So that was a theme of Wolflight the song, but there is also a central theme running through Wolflight the album, which is the idea of freedom and people not being tied down.

So the Wolflight idea was, on one level, the literal connection it had with early peoples and their relationship with wolves – early friends of mankind; the journeys across land that often led us towards food and shelter.

But there are also the inner journeys people have with these animals; the shamanic idea and the relationship with the wolf on that level, for example.

Then there are the little stories on the album that have a lot to do with the basic ideas of freedom – Black Thunder for example is about slave rebellion in the old south just before the American Civil War – so the idea of freedom is very implicit on that song.

And there’s the idea of freedom running through Love Song to a Vampire too, but done with a twist.

RM: That twist you mentioned is where you have taken the harsh reality of an abusive relationship and transferred it to a dark fantasy world of vampires and control.

Love Song to a Vampire is an emotive and powerful song, both lyrically and musically – that's not something you come up with in a fifteen minute writing session…

SH: I’m glad you enjoyed that song. It’s another – in terms of the writing – that’s a construct between Jo and me. In fact it’s been very much a partnership, putting together these tunes, as well as the input from Roger King, our co-producer and keyboard player – Roger was taking these tunes just that little bit further as we were recording them; that was important too.

Many of the songs on the album really are stories and as you alluded to it did take a while to come up with this one – particularly with where it was going to go musically.

We had the lyric beforehand but we actually struggled to find a chorus for it – in fact we struggled to find the music for it too, but I’m very pleased with the way Love Song to a Vampire came out...

Steve Hackett’s previous album of all-new material, 2011s Beyond the Shrouded Horizon, was an excellent mix of musical vignettes and larger rock-meets-orchestra pieces.

Beyond the Shrouded Horizon was followed by Genesis Revisited II, the Revisited II Selection album and the highly successful Genesis Revisited tour shows.

In 2015, four decades on from his debut solo album Voyage of the Acolyte and a subsequent body of work that includes progressive, world music, instrumental and classical genre releases, Steve Hackett celebrated his 40th Anniversary as a solo artist by bathing in the Wolflight of another Top 40 album success and his most accomplished and striking work to date.

2015 is also a year destined to be one of the noted guitarist’s best.

Following the release of Wolflight and the album's deserved critical acclaim came the announcement of Autumn dates in Europe and the UK (with follow-on US dates) that will celebrate the Acolyte to Wolflight 40th Anniversary and dip back in to the Genesis back catalogue that featured Steve Hackett when the band were at the peak of their progressive powers.

However anyone looking for anecdotes about lambs lying down or tricks of a particular tail will have to look elsewhere – the Muirsical Conversation that follows concentrated on Steve Hackett’s solo career with specific emphasis on Wolflight, an album that has as interesting a story attached to its origins as it has outstanding musical stories within…

Ross Muir: Wolflight is both delicate and complex in construction with a lot of light and shade.

Well arranged harmonies and melody lines mesh with folk, world music, heavy rock and even a little blues to produce an album that's almost operatic in scope – and that’s before we even look at the lyrical themes.

How did you conceive and develop Wolflight and come up with such a concept?

Steve Hackett: Well first of all the title derives from an article my wife Jo did some years back; it might even be as much as ten years ago now. Jo wrote an article for a magazine which talked about the Wolflight, the hour just before the dawn when wolves start to hunt.

Now, as far as we know, the earliest references to Wolflight in literature is in the Odyssey – Homer referring to Odysseus when he wakes up in the Wolflight – but while the references are that old we found not that many people had heard of the concept. So that formed the basic idea for the album, which we started to write between us – and the darkness-to-light hour of the Wolflight just seemed to be the perfect title for it.

Then photographer friends of ours, Maurizio and Angéla Vicedomini, who have been doing album covers for us recently, discovered a guy who was raising wolves in a place about one hour outside of Rome.

Maurizio and Angéla said we could possibly meet up with this guy and his wife to take photos of the wolves, so we went out there and spent a day doing just that… and that’s just the outer wrappings of the album and the title track!

RM: Pretty impressive wrappings and I so envy you that time with the wolves. And the lyrical themes?

SH: Well, another reason we were drawn to the idea of Wolflight as a title was that we were writing a song about early peoples; the nomadic tribes who took on the Chinese – the ones for whom the Great Wall of China was built to keep them out – and the people who eventually over-ran the Roman Empire and brought down the Romans.

So that was a theme of Wolflight the song, but there is also a central theme running through Wolflight the album, which is the idea of freedom and people not being tied down.

So the Wolflight idea was, on one level, the literal connection it had with early peoples and their relationship with wolves – early friends of mankind; the journeys across land that often led us towards food and shelter.

But there are also the inner journeys people have with these animals; the shamanic idea and the relationship with the wolf on that level, for example.

Then there are the little stories on the album that have a lot to do with the basic ideas of freedom – Black Thunder for example is about slave rebellion in the old south just before the American Civil War – so the idea of freedom is very implicit on that song.

And there’s the idea of freedom running through Love Song to a Vampire too, but done with a twist.

RM: That twist you mentioned is where you have taken the harsh reality of an abusive relationship and transferred it to a dark fantasy world of vampires and control.

Love Song to a Vampire is an emotive and powerful song, both lyrically and musically – that's not something you come up with in a fifteen minute writing session…

SH: I’m glad you enjoyed that song. It’s another – in terms of the writing – that’s a construct between Jo and me. In fact it’s been very much a partnership, putting together these tunes, as well as the input from Roger King, our co-producer and keyboard player – Roger was taking these tunes just that little bit further as we were recording them; that was important too.

Many of the songs on the album really are stories and as you alluded to it did take a while to come up with this one – particularly with where it was going to go musically.

We had the lyric beforehand but we actually struggled to find a chorus for it – in fact we struggled to find the music for it too, but I’m very pleased with the way Love Song to a Vampire came out...

SH: You noted earlier that the album has operatic scope and it certainly genre hops between things that you might expect in folk music – sitting around the camp fire playing folk tunes – to bits of pop music, bits of rock music, some blues… and all with orchestral salvos being fired across it at regular intervals!

As well as that we have older, world music instruments that will be less familiar to people.

The idea was really to have all those genres appearing in cameo throughout so that you didn’t get those long guitar solos; I felt that nothing should really outstay its welcome and I was conscious of wanting to make an album that would appeal to people that get bored very easily – as progressive rock listeners sometimes do...

RM: You’ve just put the nail on the progressive head, Steve, certainly as far as I’m concerned.

Progressive rock is at its worst – and musically embarrassing to be honest – when it outstays its welcome, or someone decides to make a piece twenty minutes long just because they can, not because they have twenty minutes of dynamic or interesting music.

One of your greatest strengths is having that musical "sense" of how long a piece should be; Wolflight is weighted perfectly in that regard. It's also, for me, your most striking and accomplished work.

SH: Thank you for saying that. I haven’t been listening to it very much recently but funnily enough just this very day I was playing the album. And as it was playing I was struck by a number of things…

When you make an album you are obviously very close to it and I’m still very much in love with Wolflight – I’m still in the Honeymoon period, so to speak [laughs] – but it is very good.

But you can have too much of a good thing; you can listen to an album too many times and eventually you don’t see or hear it for what it actually is. And as the artist you might end up getting too involved – "this track would be great with a video" or "that track could maybe be a single" and then you’re also thinking in terms about what numbers will be best to play live…

All of which distracts you from whether the album even hangs together or not – you really need the distance of time to do that. But I must say that today, while I was reading Shout! – Philip Norman’s book about the Beatles – I had the album playing in the background and I could actually see and hear the link between Wolflight and all of British music.

It almost seemed as if the genres were appearing just like runners in a relay race where, as each runner tires, the baton is handed over to the next…

RM: That’s a great analogy. As I was listening to you I couldn’t help but think – as I’m sure a lot of people reading this will also think – "reading about the Beatles while playing Wolflight? I’ve had worse days…"

SH: [laughs] But what I’m saying is I got distracted by what I was hearing.

Often when you’re sitting down to an album you’re "listening" to it – it goes straight to the conscious mind with its ability to criticize, comment and grade. But if an album is playing in the background and you’re doing something else you’re "hearing" it; I’ve always thought that.

In fact some of the best tracks I’ve heard have been when I’m out in the street or doing something else and some song just happens to be playing somewhere. So it’s often how you are hearing something.

Time and time again I’ve put on other peoples albums and I’m sitting there like the Russian judge at an ice skating contest [laughter] thinking "yeah… it’s hard to get fired up by this" yet at another time you can hear exactly the same piece of music while you’re doing something else – it could be buying the groceries, looking at shirts, anything at all in fact – and you hear something and think "wow, that sounds really great… wait a minute, that’s the song I’ve already dismissed!" [laughs]

All of which makes me realise how subjective even my own judgement can be!

RM: And in this day and age we are listening to things in so many ways at different times.

When I’m listening as a reviewer, there can be so much going on that the music is just one of a number of things I’m interacting with – but if something is filtering through and making an impact on your consciousness at that background level, it clearly has something…

SH: Yes, exactly. I must admit it’s very nice when I hear something that I’m moved by and there is a lot of good stuff out there at the moment, but it’s finding it, isn’t it?

We are in overload permanently, so you feel like the river is being clogged up by a welter of this stuff; it’s very difficult to discern and give merit where it’s due.

As well as that we have older, world music instruments that will be less familiar to people.

The idea was really to have all those genres appearing in cameo throughout so that you didn’t get those long guitar solos; I felt that nothing should really outstay its welcome and I was conscious of wanting to make an album that would appeal to people that get bored very easily – as progressive rock listeners sometimes do...

RM: You’ve just put the nail on the progressive head, Steve, certainly as far as I’m concerned.

Progressive rock is at its worst – and musically embarrassing to be honest – when it outstays its welcome, or someone decides to make a piece twenty minutes long just because they can, not because they have twenty minutes of dynamic or interesting music.

One of your greatest strengths is having that musical "sense" of how long a piece should be; Wolflight is weighted perfectly in that regard. It's also, for me, your most striking and accomplished work.

SH: Thank you for saying that. I haven’t been listening to it very much recently but funnily enough just this very day I was playing the album. And as it was playing I was struck by a number of things…

When you make an album you are obviously very close to it and I’m still very much in love with Wolflight – I’m still in the Honeymoon period, so to speak [laughs] – but it is very good.

But you can have too much of a good thing; you can listen to an album too many times and eventually you don’t see or hear it for what it actually is. And as the artist you might end up getting too involved – "this track would be great with a video" or "that track could maybe be a single" and then you’re also thinking in terms about what numbers will be best to play live…

All of which distracts you from whether the album even hangs together or not – you really need the distance of time to do that. But I must say that today, while I was reading Shout! – Philip Norman’s book about the Beatles – I had the album playing in the background and I could actually see and hear the link between Wolflight and all of British music.

It almost seemed as if the genres were appearing just like runners in a relay race where, as each runner tires, the baton is handed over to the next…

RM: That’s a great analogy. As I was listening to you I couldn’t help but think – as I’m sure a lot of people reading this will also think – "reading about the Beatles while playing Wolflight? I’ve had worse days…"

SH: [laughs] But what I’m saying is I got distracted by what I was hearing.

Often when you’re sitting down to an album you’re "listening" to it – it goes straight to the conscious mind with its ability to criticize, comment and grade. But if an album is playing in the background and you’re doing something else you’re "hearing" it; I’ve always thought that.

In fact some of the best tracks I’ve heard have been when I’m out in the street or doing something else and some song just happens to be playing somewhere. So it’s often how you are hearing something.

Time and time again I’ve put on other peoples albums and I’m sitting there like the Russian judge at an ice skating contest [laughter] thinking "yeah… it’s hard to get fired up by this" yet at another time you can hear exactly the same piece of music while you’re doing something else – it could be buying the groceries, looking at shirts, anything at all in fact – and you hear something and think "wow, that sounds really great… wait a minute, that’s the song I’ve already dismissed!" [laughs]

All of which makes me realise how subjective even my own judgement can be!

RM: And in this day and age we are listening to things in so many ways at different times.

When I’m listening as a reviewer, there can be so much going on that the music is just one of a number of things I’m interacting with – but if something is filtering through and making an impact on your consciousness at that background level, it clearly has something…

SH: Yes, exactly. I must admit it’s very nice when I hear something that I’m moved by and there is a lot of good stuff out there at the moment, but it’s finding it, isn’t it?

We are in overload permanently, so you feel like the river is being clogged up by a welter of this stuff; it’s very difficult to discern and give merit where it’s due.

RM: I mentioned earlier that I feel Wolflight is a perfectly weighted album and part of that equation is the balance across the tracks.

Sharing space with the more complex pieces are the delicate instrumental Earthshine, the acoustic-based Loving Sea and Heartsong, the charming little album closer.

SH: Wolflight is the kind of album I’ve been trying to make for a long time and when I play it to myself I do think "every single idea came off; I’m not embarrassed by anything we did."

On a basic level Wolflight is a journey through different styles – and I think it’s a good ride – but as we've spoken about there are obviously deeper levels or themes there, too.

Jo and I talked about those themes as we were writing and quite often Jo would lead the way lyrically or musically. Jo came up with the words for Corycian Fire for instance.

RM: That’s another great multi-genre adventure, from Middle Eastern motifs to progressive and heavy rock. The Corycian cave in Greece is clearly a huge inspiration for you both...

SH: Yes; Jo is a great Grecophile and a great expert on much of our ancient history.

In Delphi, a place we have visited several times between us, we discovered the place where divination took place originally, before the early site was sacked by Christian Monks.

And you really do get a sense of something spectacular, haunting and even spooky from this particular place. The Korikion Antron has almost cathedral like proportions but it’s a natural phenomenon on the slopes of Mount Parnassus; it’s hidden away in the mountains.

And the shapes of the stalactites and stalagmites are just extraordinary. Many of them look sculpted even although they are natural formations; they look eerily like living beings.

So on Corycian Fire we tried to capture that atmosphere and then, right at the end of that track, we have a choir singing in Ancient Greek.

RM: I love big hairs-on-neck choral arrangements and the power of voice – or voices.

The use of a choir at the end of that track, and in such a manner, was inspired…

SH: I just think it can be a good idea to take things to the limit – or in this case to take the voices to the mountains [laughs] – and be able to step outside of rock and roll and have things that are on the periphery. Choirs don’t usually show up in rock and roll, although obviously they can make guest appearances from time to time, so although I wanted to do a rock album I wanted one that had differences.

I played the album to my brother just after it was completed and he said "it’s got a cinematic quality to it."

I was always trying to get that quality of enlargement in to rock arrangements – doubling bass guitars for example, or sometimes orchestras will be in there but invisibly so, only there to enlarge the existing action.

I think subliminal sounds can sometimes make things quite large – for instance we’ve got brass doubling some of the bass guitar stabs; that gives a kind of definition that electric instruments on their own don’t necessarily have.

We’ve also mixed real instrumentation with samples and that’s part of the reason the album sounds the way that it does – but technology is so seamless these days I often can’t tell the difference between the real thing and the real thing [laughs]

Actually the difference really is that not all of it is in real time – we try to get as many acoustic instruments as we can on there but I often have some parts ghosted by samples in order to give it that weight, or something symphonic.

I have worked with orchestras in the past but the question is how big is your budget and how much are you prepared to track up – and if you are working with an orchestra you can also end up running in to Union problems. So it tends to be a small group of players that we track up and work with it in that manner.

But if it was up to me and I had an endless budget with every album it would be a case of "yes, let’s have an orchestra and let’s have a choir" but very often you cut your cloth to suit the means of each successive project – it’s not every time that I’m going to be able to go out and work with the Royal Philharmonic!

RM: No indeed not but the end results of Wolflight, with its mix of genres and integration of acoustic and electric instrumentation, samples, brass and choirs, speak for themselves.

You mentioned Wolflight being a journey through different styles and that parallels your entire career – an interesting and rewarding musical journey that has led to critically acclaimed albums of differing styles including progressive, instrumental, classical, world music and even a little blues.

Is such diversification, or mixing a myriad of styles, what keeps it fresh for you?

SH: Well, I’m aware of the fact that we’re living in a world where multi-cultural diversity is under threat with the rise of fundamentalism but it seems to me that you have to have an ability to listen to people from different cultures and mix with it. That diversity has always been a calling card for me.

I remember when I did Please Don’t Touch, the first solo album I did after I left Genesis, Tony Stratton-Smith, the label boss of Charisma, said to me of Please Don’t Touch that "diversity is both the album’s strength and its weakness."

Tony’s opinion I respected very much because he was an extremely gregarious, brilliant man but I think I was determined to make that diversity my calling card from then on.

I wanted to make the kind of albums that worked pretty much in the same way the CBS sampler albums did in the late sixties.

RM: Their compilations of various and sometimes very different label-mate artists.

SH: Yes, that’s right. You had artists on those albums such as Leonard Cohen, Simon and Garfunkel, Blood Sweat and Tears and Roy Harper, just to mention a few – so from track to track you had a whole bunch of different artists.

And around the same time there was Switched On Bach by Wendy Carlos, but then credited as Walter Carlos. So what people were listening to at home, at that time, could be extremely diverse.

And I think also that psychedelic music, for all its shortcomings, was a ground-breaking area for abandoning the rules but at the same time everyone was invited to the party.

Then once the Beatles started to develop and had the world’s ear that all coloured music in such a way that it made it impossible to go back to the black and white version.

Because you know, once you had seen all the colours of the rainbow and the start of world music you would assume that music was going to remain as adventurous from then on but actually, no – and in fact I think it became more parochial.

American music in particular became more basic and English music – looking at where it is today – is mainly the product of producers and programmers.

They also write of course, but often what gets lost I think is the craft of song writing.

Sharing space with the more complex pieces are the delicate instrumental Earthshine, the acoustic-based Loving Sea and Heartsong, the charming little album closer.

SH: Wolflight is the kind of album I’ve been trying to make for a long time and when I play it to myself I do think "every single idea came off; I’m not embarrassed by anything we did."

On a basic level Wolflight is a journey through different styles – and I think it’s a good ride – but as we've spoken about there are obviously deeper levels or themes there, too.

Jo and I talked about those themes as we were writing and quite often Jo would lead the way lyrically or musically. Jo came up with the words for Corycian Fire for instance.

RM: That’s another great multi-genre adventure, from Middle Eastern motifs to progressive and heavy rock. The Corycian cave in Greece is clearly a huge inspiration for you both...

SH: Yes; Jo is a great Grecophile and a great expert on much of our ancient history.

In Delphi, a place we have visited several times between us, we discovered the place where divination took place originally, before the early site was sacked by Christian Monks.

And you really do get a sense of something spectacular, haunting and even spooky from this particular place. The Korikion Antron has almost cathedral like proportions but it’s a natural phenomenon on the slopes of Mount Parnassus; it’s hidden away in the mountains.

And the shapes of the stalactites and stalagmites are just extraordinary. Many of them look sculpted even although they are natural formations; they look eerily like living beings.

So on Corycian Fire we tried to capture that atmosphere and then, right at the end of that track, we have a choir singing in Ancient Greek.

RM: I love big hairs-on-neck choral arrangements and the power of voice – or voices.

The use of a choir at the end of that track, and in such a manner, was inspired…

SH: I just think it can be a good idea to take things to the limit – or in this case to take the voices to the mountains [laughs] – and be able to step outside of rock and roll and have things that are on the periphery. Choirs don’t usually show up in rock and roll, although obviously they can make guest appearances from time to time, so although I wanted to do a rock album I wanted one that had differences.

I played the album to my brother just after it was completed and he said "it’s got a cinematic quality to it."

I was always trying to get that quality of enlargement in to rock arrangements – doubling bass guitars for example, or sometimes orchestras will be in there but invisibly so, only there to enlarge the existing action.

I think subliminal sounds can sometimes make things quite large – for instance we’ve got brass doubling some of the bass guitar stabs; that gives a kind of definition that electric instruments on their own don’t necessarily have.

We’ve also mixed real instrumentation with samples and that’s part of the reason the album sounds the way that it does – but technology is so seamless these days I often can’t tell the difference between the real thing and the real thing [laughs]

Actually the difference really is that not all of it is in real time – we try to get as many acoustic instruments as we can on there but I often have some parts ghosted by samples in order to give it that weight, or something symphonic.

I have worked with orchestras in the past but the question is how big is your budget and how much are you prepared to track up – and if you are working with an orchestra you can also end up running in to Union problems. So it tends to be a small group of players that we track up and work with it in that manner.

But if it was up to me and I had an endless budget with every album it would be a case of "yes, let’s have an orchestra and let’s have a choir" but very often you cut your cloth to suit the means of each successive project – it’s not every time that I’m going to be able to go out and work with the Royal Philharmonic!

RM: No indeed not but the end results of Wolflight, with its mix of genres and integration of acoustic and electric instrumentation, samples, brass and choirs, speak for themselves.

You mentioned Wolflight being a journey through different styles and that parallels your entire career – an interesting and rewarding musical journey that has led to critically acclaimed albums of differing styles including progressive, instrumental, classical, world music and even a little blues.

Is such diversification, or mixing a myriad of styles, what keeps it fresh for you?

SH: Well, I’m aware of the fact that we’re living in a world where multi-cultural diversity is under threat with the rise of fundamentalism but it seems to me that you have to have an ability to listen to people from different cultures and mix with it. That diversity has always been a calling card for me.

I remember when I did Please Don’t Touch, the first solo album I did after I left Genesis, Tony Stratton-Smith, the label boss of Charisma, said to me of Please Don’t Touch that "diversity is both the album’s strength and its weakness."

Tony’s opinion I respected very much because he was an extremely gregarious, brilliant man but I think I was determined to make that diversity my calling card from then on.

I wanted to make the kind of albums that worked pretty much in the same way the CBS sampler albums did in the late sixties.

RM: Their compilations of various and sometimes very different label-mate artists.

SH: Yes, that’s right. You had artists on those albums such as Leonard Cohen, Simon and Garfunkel, Blood Sweat and Tears and Roy Harper, just to mention a few – so from track to track you had a whole bunch of different artists.

And around the same time there was Switched On Bach by Wendy Carlos, but then credited as Walter Carlos. So what people were listening to at home, at that time, could be extremely diverse.

And I think also that psychedelic music, for all its shortcomings, was a ground-breaking area for abandoning the rules but at the same time everyone was invited to the party.

Then once the Beatles started to develop and had the world’s ear that all coloured music in such a way that it made it impossible to go back to the black and white version.

Because you know, once you had seen all the colours of the rainbow and the start of world music you would assume that music was going to remain as adventurous from then on but actually, no – and in fact I think it became more parochial.

American music in particular became more basic and English music – looking at where it is today – is mainly the product of producers and programmers.

They also write of course, but often what gets lost I think is the craft of song writing.

From Acolyte to Wolflight... Steve Hackett's voyage as a solo artist started in 1975 but forty

years on, having released a large body of work covering a diverse range of musical genres

the noted guitarist can bathe in the Wolflight of his most accomplished solo work to date.

SH: I think to write a decent song you need to be open to everything – you need to be open to films, to poetry, and ideally the writer needs to be able to do what Lennon and McCartney were able to do in the sixties, which was to act as a kind of Camera Obscura, looking at flashpoints in imaginary people’s lives.

That’s what I loved so much about them; the fact that they used the third person so well yet seemed to make those songs so personal – She’s Leaving Home is a prime example of that.

And often their songs were very short but so much was said. I always point to Eleanor Rigby – the story of a woman at the end of her life and the subtext of loneliness – yet all in a very short song.

So that’s always been the challenge for me – although I suspect I’ve not quite mastered the art of saying it in two minutes, or even a few minutes!

RM: [laughs] Perhaps, but emotive short-form is not completely alien to you – for example on your last studio album of all-new material, Beyond the Shrouded Horizon, a number of powerful or plaintive instrumental and lyrical vignettes sit alongside larger, orchestrated pieces.

Actually I’m very fond of Shrouded Horizon; it deserved far more recognition and success than it achieved.

Mind you I’m probably always going to like any album that opens with a song called Loch Lomond [laughs]

Great song...

SH: I’m really glad you like that one! Funnily enough I was thinking about that song when I was talking to Amanda Lehmann just a couple of days ago – I was playing her a new song that I was writing and I was telling her how much I wanted her to sing on it.

I had been saying to Amanda how well I thought the vocals we did between us on Loch Lomond worked, especially the canticle aspect in the middle of the song, but it was quite tricky to do to be honest.

It's not always obvious though – I don’t always get all of the answers at once with this stuff but I love the mixture of male and female voices...

years on, having released a large body of work covering a diverse range of musical genres

the noted guitarist can bathe in the Wolflight of his most accomplished solo work to date.

SH: I think to write a decent song you need to be open to everything – you need to be open to films, to poetry, and ideally the writer needs to be able to do what Lennon and McCartney were able to do in the sixties, which was to act as a kind of Camera Obscura, looking at flashpoints in imaginary people’s lives.

That’s what I loved so much about them; the fact that they used the third person so well yet seemed to make those songs so personal – She’s Leaving Home is a prime example of that.

And often their songs were very short but so much was said. I always point to Eleanor Rigby – the story of a woman at the end of her life and the subtext of loneliness – yet all in a very short song.

So that’s always been the challenge for me – although I suspect I’ve not quite mastered the art of saying it in two minutes, or even a few minutes!

RM: [laughs] Perhaps, but emotive short-form is not completely alien to you – for example on your last studio album of all-new material, Beyond the Shrouded Horizon, a number of powerful or plaintive instrumental and lyrical vignettes sit alongside larger, orchestrated pieces.

Actually I’m very fond of Shrouded Horizon; it deserved far more recognition and success than it achieved.

Mind you I’m probably always going to like any album that opens with a song called Loch Lomond [laughs]

Great song...

SH: I’m really glad you like that one! Funnily enough I was thinking about that song when I was talking to Amanda Lehmann just a couple of days ago – I was playing her a new song that I was writing and I was telling her how much I wanted her to sing on it.

I had been saying to Amanda how well I thought the vocals we did between us on Loch Lomond worked, especially the canticle aspect in the middle of the song, but it was quite tricky to do to be honest.

It's not always obvious though – I don’t always get all of the answers at once with this stuff but I love the mixture of male and female voices...

SH: I often think that these days some of the best results come from not screaming your head off but rather by taking something from the School of Approach the crooners used way back.

My take on that is fading in to a note as you sing, so you are singing quite gently; almost starting from silence. I love singers who could do that – Roy Orbison, The Everly Brothers.

I’m really still trying to justify romance, but not necessarily always between boy and girl.

It could be the romance of place, or figures in a landscape. Or of a time.

RM: It's interesting to get your take on vocalising because I’m big on voice myself – it can make or break a song. But the vocals, folk-based verses and darker, heavy rock structures of Loch Lomond make for a great song from an album that, as I said, didn’t get the recognition it deserved.

But then outside of the core fan-base of a given artist it’s never easy to predict what will grab further attention or sales…

SH: Well, what I found with Genesis – the albums we did in my earliest days with the band – was they didn’t always sell massively at first; it was only later that further light was thrown on those records.

So there’s always time for a slow-burn and I am proud of Beyond the Shrouded Horizon.

In fact the albums that I’ve done recently with Jo – Out of the Tunnel’s Mouth and Shrouded Horizon – I see as brother and sister projects with Wolflight part of that family.

The anomaly in there was revisiting the Genesis stuff but that was with a massive team, so it became an enlargement of what we do.

With Wolflight we are back to doing what I like to think of as films for the ear rather than the eye, but with a story of course, which is very important I think – the songs I like best from other artists normally have some kind of story going on.

I remember having a conversation with Peter Gabriel when I first joined Genesis; he was saying to me that he found it very difficult to write convincing narratives.

And I think that’s the challenge – the idea that you might be able to write a story that doesn't necessarily need an explanation sheet written along with it and one that might be longer than the song itself (laughter). Hopefully the song will speak for itself and you can hear all the words first time through – although I realise you need tremendous concentration to catch every word all the way through a song the first time you hear it. But, again, the Beatles seemed to have that ability where you didn’t have to sit down with the lyric sheet every time to get the words – well, apart from I Am the Walrus of course – you needed a crib sheet to tell you where that was going [laughs] but it’s still no less marvellous!

RM: Indeed [laughs]. For all that lyrics and story are very important parts of some of your songs the other side of the Steve Hackett musical coin is a plethora of wonderful, emotive instrumentals from nylon string guitar pieces to electric fusion.

One of your finest and acclaimed instrumental numbers is Spectral Mornings, recently revisited by Rob Reed of Magenta for the wonderful charity Parkinson’s UK.

I love the uplifting, tonal beauty of Spectral Mornings but I have to say the new version, complete with lyric and sung by David Longdon and Christina Booth, has a beautiful vibrancy; a wonderful reinterpretation.

And you also appeared on it…

SH: I did, yes! My contribution was as a player and as the original writer of the instrumental melody.

But they must have picked up on the fact that at one point I had intended it to be a vocal song – it just so happened that when I played the lead line on guitar to the band I was working with at the time, everybody to a man said "that sounds really good just as the guitar melody – why don’t you do it like that!"

It was so obvious that it was staring me in the face but I hadn’t clocked it at all!

RM: Isn’t that something? One of your finest instrumental pieces nearly wasn’t [laughs]

And, after all these years, the boys and girls behind the reworking of Spectral Mornings have given you something you originally envisaged – a vocal version.

SH: Yes it’s strange isn’t it, the way that sometimes works – considering that song goes all the way back to 1979!

My take on that is fading in to a note as you sing, so you are singing quite gently; almost starting from silence. I love singers who could do that – Roy Orbison, The Everly Brothers.

I’m really still trying to justify romance, but not necessarily always between boy and girl.

It could be the romance of place, or figures in a landscape. Or of a time.

RM: It's interesting to get your take on vocalising because I’m big on voice myself – it can make or break a song. But the vocals, folk-based verses and darker, heavy rock structures of Loch Lomond make for a great song from an album that, as I said, didn’t get the recognition it deserved.

But then outside of the core fan-base of a given artist it’s never easy to predict what will grab further attention or sales…

SH: Well, what I found with Genesis – the albums we did in my earliest days with the band – was they didn’t always sell massively at first; it was only later that further light was thrown on those records.

So there’s always time for a slow-burn and I am proud of Beyond the Shrouded Horizon.

In fact the albums that I’ve done recently with Jo – Out of the Tunnel’s Mouth and Shrouded Horizon – I see as brother and sister projects with Wolflight part of that family.

The anomaly in there was revisiting the Genesis stuff but that was with a massive team, so it became an enlargement of what we do.

With Wolflight we are back to doing what I like to think of as films for the ear rather than the eye, but with a story of course, which is very important I think – the songs I like best from other artists normally have some kind of story going on.

I remember having a conversation with Peter Gabriel when I first joined Genesis; he was saying to me that he found it very difficult to write convincing narratives.

And I think that’s the challenge – the idea that you might be able to write a story that doesn't necessarily need an explanation sheet written along with it and one that might be longer than the song itself (laughter). Hopefully the song will speak for itself and you can hear all the words first time through – although I realise you need tremendous concentration to catch every word all the way through a song the first time you hear it. But, again, the Beatles seemed to have that ability where you didn’t have to sit down with the lyric sheet every time to get the words – well, apart from I Am the Walrus of course – you needed a crib sheet to tell you where that was going [laughs] but it’s still no less marvellous!

RM: Indeed [laughs]. For all that lyrics and story are very important parts of some of your songs the other side of the Steve Hackett musical coin is a plethora of wonderful, emotive instrumentals from nylon string guitar pieces to electric fusion.

One of your finest and acclaimed instrumental numbers is Spectral Mornings, recently revisited by Rob Reed of Magenta for the wonderful charity Parkinson’s UK.

I love the uplifting, tonal beauty of Spectral Mornings but I have to say the new version, complete with lyric and sung by David Longdon and Christina Booth, has a beautiful vibrancy; a wonderful reinterpretation.

And you also appeared on it…

SH: I did, yes! My contribution was as a player and as the original writer of the instrumental melody.

But they must have picked up on the fact that at one point I had intended it to be a vocal song – it just so happened that when I played the lead line on guitar to the band I was working with at the time, everybody to a man said "that sounds really good just as the guitar melody – why don’t you do it like that!"

It was so obvious that it was staring me in the face but I hadn’t clocked it at all!

RM: Isn’t that something? One of your finest instrumental pieces nearly wasn’t [laughs]

And, after all these years, the boys and girls behind the reworking of Spectral Mornings have given you something you originally envisaged – a vocal version.

SH: Yes it’s strange isn’t it, the way that sometimes works – considering that song goes all the way back to 1979!

RM: Talking of going all the way back, such reflections lead me to a final question about the Then and Now of Steve Hackett, exemplary guitarist and proud owner of a 40 year solo career and counting…

What does the 65 years young Steve Hackett think of the 20 something Steve Hackett who undertook the Voyage of a musical Acolyte or the young guitarist who started with a famous Nursery Cryme in 1971?

SH: Well… it’s actually quite difficult, looking back at one’s young self, but I think the quest is probably still the same.

I know I’ve acquired more technique and I have heard it said by others that musicians start off with passion then they acquire technique – as a consolation prize perhaps [laughs]

But I don’t see it like that. I think that it’s possible to still be passionate and acquire more technique but hopefully you can subordinate both in favour of doing the right thing, for the right song, at the right time.

In other words you might be able to play fast but it’s just as important to be able to desist! (laughs).

Let the horses go at the right moment and then give them their head – don’t keep trying to prove yourself to people, like you have to in sport.

Or perhaps it’s the difference between, say, jazz and pop – I’d much rather hear a simple song done well, although I realise of course that jazz is variation; that’s its core.

I don’t dislike jazz by any means – it’s a wonderful medium for soloists – but the variation is everything.

So although I’m an instrumentalist there is this other side of me that wants to resist the urge to keep playing fast and try… well, try to learn sing properly for start!

That’s a lifelong quest in itself – the discovery of what you can and can’t do, vocally; to realise your limitations.

Most of us have a number of voices in us – we can all make different noises from a whisper to a shout – and if we all do that in tune we ought to be able to make some very good singers indeed!

RM: Indeed we should. While you have discovered your own musical voice through song you also have an eloquent and informative voice when it comes to conversation – thanks for making my job very easy, Steve.

SH: Well thank you but I know I gave some very long answers so feel free me to edit me down; I’m not very good at using a full stop these days!

RM: No edits required – it’s been a pleasure to listen to you talk in so much detail.

And trust me, once I tidy this up with a bunch of full stops it will read as well as Wolflight plays [laughs]

SH: [laughs] I’m sure it will! Thank you!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Steve Hackett

May 2015

Click here for FabricationsHQ's Feature Review of Wolflight, including official title track video.

Steve Hackett official website: http://www.hackettsongs.com/

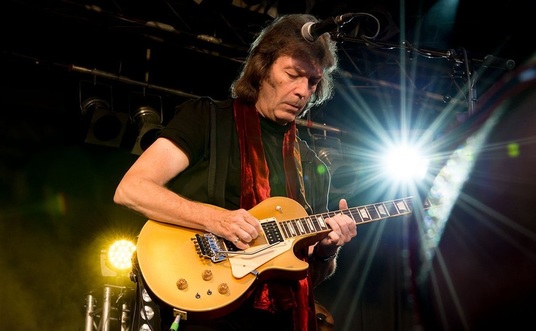

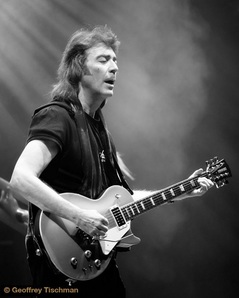

Photo Credits:

© Geoffrey Tichman (black & white image); © Clemens Mitscher/ www.stage-photography.com (colour image)

Audio tracks presented to accompany the above article and to promote the work of the artist.

No infringement of copyright is intended.

What does the 65 years young Steve Hackett think of the 20 something Steve Hackett who undertook the Voyage of a musical Acolyte or the young guitarist who started with a famous Nursery Cryme in 1971?

SH: Well… it’s actually quite difficult, looking back at one’s young self, but I think the quest is probably still the same.

I know I’ve acquired more technique and I have heard it said by others that musicians start off with passion then they acquire technique – as a consolation prize perhaps [laughs]

But I don’t see it like that. I think that it’s possible to still be passionate and acquire more technique but hopefully you can subordinate both in favour of doing the right thing, for the right song, at the right time.

In other words you might be able to play fast but it’s just as important to be able to desist! (laughs).

Let the horses go at the right moment and then give them their head – don’t keep trying to prove yourself to people, like you have to in sport.

Or perhaps it’s the difference between, say, jazz and pop – I’d much rather hear a simple song done well, although I realise of course that jazz is variation; that’s its core.

I don’t dislike jazz by any means – it’s a wonderful medium for soloists – but the variation is everything.

So although I’m an instrumentalist there is this other side of me that wants to resist the urge to keep playing fast and try… well, try to learn sing properly for start!

That’s a lifelong quest in itself – the discovery of what you can and can’t do, vocally; to realise your limitations.

Most of us have a number of voices in us – we can all make different noises from a whisper to a shout – and if we all do that in tune we ought to be able to make some very good singers indeed!

RM: Indeed we should. While you have discovered your own musical voice through song you also have an eloquent and informative voice when it comes to conversation – thanks for making my job very easy, Steve.

SH: Well thank you but I know I gave some very long answers so feel free me to edit me down; I’m not very good at using a full stop these days!

RM: No edits required – it’s been a pleasure to listen to you talk in so much detail.

And trust me, once I tidy this up with a bunch of full stops it will read as well as Wolflight plays [laughs]

SH: [laughs] I’m sure it will! Thank you!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Steve Hackett

May 2015

Click here for FabricationsHQ's Feature Review of Wolflight, including official title track video.

Steve Hackett official website: http://www.hackettsongs.com/

Photo Credits:

© Geoffrey Tichman (black & white image); © Clemens Mitscher/ www.stage-photography.com (colour image)

Audio tracks presented to accompany the above article and to promote the work of the artist.

No infringement of copyright is intended.