What Do You Want From Your Live Shows?

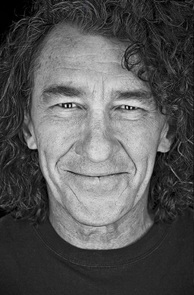

Muirsical Conversation with Fee Waybill

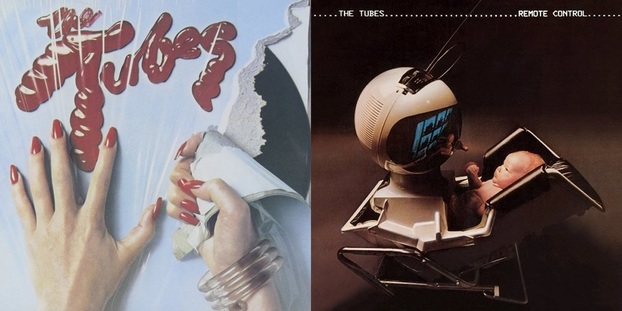

The Tubes are as famous for their on-stage theatrics and parodies as they are for their music, but that should not detract from the quality of a back catalogue that ranges from the quirk, strangeness and new wave charm of their 1970s albums to the more commercially appealing 1980s releases and on to the criminally under-heard and under-rated 1996 album Genius of America.

While those 70s albums are the band’s most musically explorative, influenced by the vibrant anything goes San Francisco of the era, their crowning achievements are the classic and conceptual Remote Control and The Completion Backward Principle, an album that featured polished power-rock but retained The Tubes stamp of musical adventure.

In 2015 The Tubes celebrate their 40th Anniversary with a tour that takes in the USA, Europe and the UK, a country that has embraced the band since their first trip to British shores in 1977.

Singer, songwriter, poet and The Tubes theatrical front man Fee Waybill – whose on-stage glam rock creation Quay Lewd has become as famous as the band – spoke to FabricationsHQ to talk about those creative and crazy San Francisco days, the band’s love of British and Scottish audiences (and a couple of very memorable but very different Scottish gigs), the incredible working methods that produced the acclaimed Remote Control, the pressures and negativity that led to a very interesting but never released album and the struggles of making new material viable in a Greatest Hits world.

But our conversation started some forty years and more ago, when a bunch of kids from Arizona reached the City by the Bay in seek of musical adventure….

Ross Muir: So, forty years of The Tubes my man… how the hell did that happen?

Fee Waybill: [laughs] I know – it’s hard to believe isn’t it? I never would have thought.

In 1975, when our first album came out, we were just a bunch of crazy kids who didn’t know what the hell we were doing – we certainly had no idea that we’d be here, playing our music, forty years later!

RM: Well The Tubes were a truly original performance rock band and your music has stood the test of time, from the multi-genre melting pot of ideas approach of the first three albums to the rock orientated, more mainstream appeal of the later albums. But to go right back to where, and how, it all started…

You relocated from Phoenix in the late sixties and headed to San Francisco, where The Tubes were born. Was that an intentional move, to catch that San Francisco and west coast vibe of anything goes?

FW: Yeah, I suppose it kind of was intentional. Our band at the time – Roger Steen, Prairie Prince, me and another bass player – moved to San Francisco first; Bill Spooner’s band moved to San Francisco a few months later.

But we all moved from Phoenix because there was just no music scene there; it was horrible and it was one hundred and twenty degrees there – every day!

Alice Cooper was in Phoenix too; he had moved there from Michigan but he eventually left Phoenix to go to Los Angeles and try and break from there. We knew Alice back then; we’ve known him for years and we’ve played concerts with him dozens of times.

RM: The Alice Cooper Band and, later, Alice as a solo artist would go on to become the theatrical rock and roll act but The Tubes had such an incredible musical diversity as well as the character driven social commentaries and parodies of the live shows…

FW: We just had so many influences. Rick Anderson is a great bass player and Prairie is such a great drummer, but Prairie and Mike Cotton were also artists.

Prairie was an amazing artist and Mike was a great graphic designer. I was the theatrical one; I was a Drama Major at Arizona State University and had done plays and theatre my whole life to that point.

Vince Welnick was a classically trained piano player – he played Beethoven all day long!

Bill Spooner just loved the blues – he was our blues player – while Roger Steen was the Jimi Hendrix guy.

Roger was Mr Psychedelia; he had a little solo band before we got together and he played Hendrix.

So we had all these influences that were dumped in to this melting pot that was San Francisco.

We moved there in 1969 just two years after the Summer of Love; it was so radically different from where we had grown up. Arizona is so conservative; one of the most conservative states in the whole of America.

So from that we’re thrown in to San Francisco with its Flower Children, its homosexual population, its leather and bondage, the nudity… San Francisco was just wide open at that time; there really were no rules...

While those 70s albums are the band’s most musically explorative, influenced by the vibrant anything goes San Francisco of the era, their crowning achievements are the classic and conceptual Remote Control and The Completion Backward Principle, an album that featured polished power-rock but retained The Tubes stamp of musical adventure.

In 2015 The Tubes celebrate their 40th Anniversary with a tour that takes in the USA, Europe and the UK, a country that has embraced the band since their first trip to British shores in 1977.

Singer, songwriter, poet and The Tubes theatrical front man Fee Waybill – whose on-stage glam rock creation Quay Lewd has become as famous as the band – spoke to FabricationsHQ to talk about those creative and crazy San Francisco days, the band’s love of British and Scottish audiences (and a couple of very memorable but very different Scottish gigs), the incredible working methods that produced the acclaimed Remote Control, the pressures and negativity that led to a very interesting but never released album and the struggles of making new material viable in a Greatest Hits world.

But our conversation started some forty years and more ago, when a bunch of kids from Arizona reached the City by the Bay in seek of musical adventure….

Ross Muir: So, forty years of The Tubes my man… how the hell did that happen?

Fee Waybill: [laughs] I know – it’s hard to believe isn’t it? I never would have thought.

In 1975, when our first album came out, we were just a bunch of crazy kids who didn’t know what the hell we were doing – we certainly had no idea that we’d be here, playing our music, forty years later!

RM: Well The Tubes were a truly original performance rock band and your music has stood the test of time, from the multi-genre melting pot of ideas approach of the first three albums to the rock orientated, more mainstream appeal of the later albums. But to go right back to where, and how, it all started…

You relocated from Phoenix in the late sixties and headed to San Francisco, where The Tubes were born. Was that an intentional move, to catch that San Francisco and west coast vibe of anything goes?

FW: Yeah, I suppose it kind of was intentional. Our band at the time – Roger Steen, Prairie Prince, me and another bass player – moved to San Francisco first; Bill Spooner’s band moved to San Francisco a few months later.

But we all moved from Phoenix because there was just no music scene there; it was horrible and it was one hundred and twenty degrees there – every day!

Alice Cooper was in Phoenix too; he had moved there from Michigan but he eventually left Phoenix to go to Los Angeles and try and break from there. We knew Alice back then; we’ve known him for years and we’ve played concerts with him dozens of times.

RM: The Alice Cooper Band and, later, Alice as a solo artist would go on to become the theatrical rock and roll act but The Tubes had such an incredible musical diversity as well as the character driven social commentaries and parodies of the live shows…

FW: We just had so many influences. Rick Anderson is a great bass player and Prairie is such a great drummer, but Prairie and Mike Cotton were also artists.

Prairie was an amazing artist and Mike was a great graphic designer. I was the theatrical one; I was a Drama Major at Arizona State University and had done plays and theatre my whole life to that point.

Vince Welnick was a classically trained piano player – he played Beethoven all day long!

Bill Spooner just loved the blues – he was our blues player – while Roger Steen was the Jimi Hendrix guy.

Roger was Mr Psychedelia; he had a little solo band before we got together and he played Hendrix.

So we had all these influences that were dumped in to this melting pot that was San Francisco.

We moved there in 1969 just two years after the Summer of Love; it was so radically different from where we had grown up. Arizona is so conservative; one of the most conservative states in the whole of America.

So from that we’re thrown in to San Francisco with its Flower Children, its homosexual population, its leather and bondage, the nudity… San Francisco was just wide open at that time; there really were no rules...

FW: In those early days in San Francisco we also had topless dancers – and I mean totally topless – on stage but nobody cared! You could get away with anything back then; it was no big deal.

RM: Yep. Just part of the San Francisco fabric back then; part of the culture…

FW: Right; that was our scene and we were immersing ourselves in it because it was so different from what we had grown up in. We had been so restricted and we just went nuts there [laughter].

Really, we went crazy – there were no rules and no limits; you could do whatever you wanted to do.

You remember back in the seventies when we had streaking?

RM: I do indeed – and that bloody novelty song we had to suffer from Ray Stevens [laughs].

FW: And we had all these guys running across baseball fields naked, or a football field, or wherever.

We did a concert a couple of times in San Francisco that we called The Streakers’ Ball; we advertised it as "if you come naked, you get in free!"

We played at a little club in Columbus Avenue and we had a line, from outside the door, of about three hundred people – all naked, with their clothes in a bag! [laughter].

But that was the deal. You come in, you streak through the audience, then you go put your clothes on.

RM: Fantastic [laughs].

FW: Yeah, and then I streaked during our show. At some point during the performance I stripped down naked and streaked the audience – I ran out in to the audience and then I ran back – and nobody batted an eye!

We thought there might be a problem when the police showed up but they just looked in and went "Oh, ok, no problem. See ya" and left! No one got arrested for nudity and there was no problem at all.

RM: If that had been any other era – or any other city – you would have been arrested on sight and it would have been "see you in court." But the fact it was San Francisco and the fact that this was the late sixties and early seventies? That was almost mandatory behaviour [laughs].

FW: Yeah, but the mistake we made was thinking we could get away with that wherever we went [laughs].

We thought we would get away with that in Kansas… boy that was a big no-no [laughter].

We got arrested and we got this, we got that – and then we got banned from other cities, mostly in the south, where it was "No, you can’t come here; you can’t do that."

So over the years it became more and more difficult to carry San Francisco to the rest of the USA and then the rest of the world. I mean we even got banned where? Why, in Portsmouth of course! [laughter].

Yep, we got banned in Portsmouth, UK. We never got banned in Scotland though; Scotland’s pretty cool.

RM: A lot of the more progressive, innovative or doing-something-a-little-bit-different bands who first played here in the late sixties or early seventies will tell you that Scottish audiences have an appreciation for good music and will give it the opportunity, no matter what the genre is and no matter how it may be presented.

That’s been especially true of Glasgow audiences for decades.

FW: I really enjoy it in Scotland. The last time we toured Europe we only played two dates in the UK unfortunately – one was in London but the other was in Dunfermline, just across the Firth of Forth.

And that was in Carnegie Hall!

RM: Quite the distinguished gig…

FW: Supposedly that was only the second Carnegie Hall, named after Andrew Carnegie.

At least that’s what they told me! [laughs].

RM: Oh that’s no yarn to yank along the American [laughs]; it was indeed built in honour of the famous industrialist and philanthropist. Andrew Carnegie came from Dunfermline but made his name in his adopted home of New York, where he funded the construction of the first and most famous Carnegie Hall.

FW: We played in this fabulous, I mean fabulous, room in Carnegie Hall; we sold out and the place went nuts! They went crazy! And we’ve also played that small club… gosh, what was it called… King Tut’s?

RM: King Tut’s is probably Glasgow’s best – and favourite – small venue. There’s a fantastic atmosphere generated in that place, probably because it’s such an intimate and enclosed space with the stage at near-audience level.

FW: It was a tiny little place but I’ll never forget it – it was just jammed to the rafters; completely packed.

And there was no place for me to change – I ended up doing my quick-changes on the fire escape [laughs], which was just outside a window by the side of the stage.

I had to use this little landing on a fire escape because the place was just so jammed; that gig was amazing.

RM: From the prestigious Carnegie Hall in Dunfermline to the fire escape of King Tuts [laughs].

Of course earlier gigs at other famous UK venues included the run of dates at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in 1977; that led to the double live album What Do You Want From Live.

FW: Back then we had a Welshman for a manager; his name was Ricki Farr and he was the son of the Welsh and British heavyweight champion Tommy Farr.

Ricki was living in L.A. at the time; he had a sound and light company and we used his gear a lot.

We really liked Ricki; we thought he was a brilliant guy so we asked him to be our manager – and the first thing he said to us was "I’ve got to take you guys to the UK – I have to get you to the UK immediately!"

Because doing the kind of sarcastic, social commentary that we were doing, he said the UK would love that. Ricki told us "they love nothing more than watching an American taking the piss out of himself!" [laughter]. But that was our deal back then; we made fun out of everything and did parodies on all kinds of different subjects.

So we came over to England and the place went nuts – the place went crazy – and ever since then we’ve known when we come over they are going to love it, because we’re gonna make fun of something and whatever it is they’re going to like it!

RM: Yep. Just part of the San Francisco fabric back then; part of the culture…

FW: Right; that was our scene and we were immersing ourselves in it because it was so different from what we had grown up in. We had been so restricted and we just went nuts there [laughter].

Really, we went crazy – there were no rules and no limits; you could do whatever you wanted to do.

You remember back in the seventies when we had streaking?

RM: I do indeed – and that bloody novelty song we had to suffer from Ray Stevens [laughs].

FW: And we had all these guys running across baseball fields naked, or a football field, or wherever.

We did a concert a couple of times in San Francisco that we called The Streakers’ Ball; we advertised it as "if you come naked, you get in free!"

We played at a little club in Columbus Avenue and we had a line, from outside the door, of about three hundred people – all naked, with their clothes in a bag! [laughter].

But that was the deal. You come in, you streak through the audience, then you go put your clothes on.

RM: Fantastic [laughs].

FW: Yeah, and then I streaked during our show. At some point during the performance I stripped down naked and streaked the audience – I ran out in to the audience and then I ran back – and nobody batted an eye!

We thought there might be a problem when the police showed up but they just looked in and went "Oh, ok, no problem. See ya" and left! No one got arrested for nudity and there was no problem at all.

RM: If that had been any other era – or any other city – you would have been arrested on sight and it would have been "see you in court." But the fact it was San Francisco and the fact that this was the late sixties and early seventies? That was almost mandatory behaviour [laughs].

FW: Yeah, but the mistake we made was thinking we could get away with that wherever we went [laughs].

We thought we would get away with that in Kansas… boy that was a big no-no [laughter].

We got arrested and we got this, we got that – and then we got banned from other cities, mostly in the south, where it was "No, you can’t come here; you can’t do that."

So over the years it became more and more difficult to carry San Francisco to the rest of the USA and then the rest of the world. I mean we even got banned where? Why, in Portsmouth of course! [laughter].

Yep, we got banned in Portsmouth, UK. We never got banned in Scotland though; Scotland’s pretty cool.

RM: A lot of the more progressive, innovative or doing-something-a-little-bit-different bands who first played here in the late sixties or early seventies will tell you that Scottish audiences have an appreciation for good music and will give it the opportunity, no matter what the genre is and no matter how it may be presented.

That’s been especially true of Glasgow audiences for decades.

FW: I really enjoy it in Scotland. The last time we toured Europe we only played two dates in the UK unfortunately – one was in London but the other was in Dunfermline, just across the Firth of Forth.

And that was in Carnegie Hall!

RM: Quite the distinguished gig…

FW: Supposedly that was only the second Carnegie Hall, named after Andrew Carnegie.

At least that’s what they told me! [laughs].

RM: Oh that’s no yarn to yank along the American [laughs]; it was indeed built in honour of the famous industrialist and philanthropist. Andrew Carnegie came from Dunfermline but made his name in his adopted home of New York, where he funded the construction of the first and most famous Carnegie Hall.

FW: We played in this fabulous, I mean fabulous, room in Carnegie Hall; we sold out and the place went nuts! They went crazy! And we’ve also played that small club… gosh, what was it called… King Tut’s?

RM: King Tut’s is probably Glasgow’s best – and favourite – small venue. There’s a fantastic atmosphere generated in that place, probably because it’s such an intimate and enclosed space with the stage at near-audience level.

FW: It was a tiny little place but I’ll never forget it – it was just jammed to the rafters; completely packed.

And there was no place for me to change – I ended up doing my quick-changes on the fire escape [laughs], which was just outside a window by the side of the stage.

I had to use this little landing on a fire escape because the place was just so jammed; that gig was amazing.

RM: From the prestigious Carnegie Hall in Dunfermline to the fire escape of King Tuts [laughs].

Of course earlier gigs at other famous UK venues included the run of dates at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in 1977; that led to the double live album What Do You Want From Live.

FW: Back then we had a Welshman for a manager; his name was Ricki Farr and he was the son of the Welsh and British heavyweight champion Tommy Farr.

Ricki was living in L.A. at the time; he had a sound and light company and we used his gear a lot.

We really liked Ricki; we thought he was a brilliant guy so we asked him to be our manager – and the first thing he said to us was "I’ve got to take you guys to the UK – I have to get you to the UK immediately!"

Because doing the kind of sarcastic, social commentary that we were doing, he said the UK would love that. Ricki told us "they love nothing more than watching an American taking the piss out of himself!" [laughter]. But that was our deal back then; we made fun out of everything and did parodies on all kinds of different subjects.

So we came over to England and the place went nuts – the place went crazy – and ever since then we’ve known when we come over they are going to love it, because we’re gonna make fun of something and whatever it is they’re going to like it!

The Tubes debut album is an eclectic musical mix that features White Punks on Dope, Mondo

Bondage and What Do You Want From Life; all three remain staples of the live set. The outstanding Remote Control has an interesting lyrical story and an even more interesting recording story.

RM: Following those Hammersmith dates and the subsequent live album came the Remote Control album and tour of 1979, which included a date at yet another famous UK venue, the sadly long gone Glasgow Apollo.

I believe Remote Control to be the band’s finest hour but I also have to say, as a major Todd Rundgren fan, I love the "Todd Job" on that album – from the production and sound to the song-writing and arrangements.

How did that whole concept and what became, in effect, a collaborative project with Todd come about?

FW: Well, it was an unusual situation, first of all. Including the live album Remote Control was the fifth album we had made for A&M Records, but we had never had a hit.

White Punks On Dope did get rereleased as a single after the live album came out, and it did get some airplay and some attention, but even although we had a five album deal with the record company – which certainly doesn’t happen any more – we had never really sold that many records; we hadn’t had that much radio success.

So the record company came down hard on us for the fifth record. They said "OK, we’re only going to give you this much money and you only have that much time to get a record done."

So we were really under the gun on that one and we really weren’t prepared for that; we didn’t have all the songs written but I did have this idea of the boy who grows up watching television – which I pretty much stole from Jerzy Kosinski and his book called Being There [laughs].

But back then I figured "well, nobody has ever heard of this guy; nobody has ever heard of his book and this is a great idea. I want to morph it and mutate it into music in a Tubes-type style."

I presented the concept to Todd, he said "yeah, ok, that’s a pretty good idea," we all headed for the studio and we ended up writing and recording each song for the album, together, in the same day!

RM: Wow [laughs].

FW: Yeah, that’s how we did it. We booked one month in a little studio just outside of San Francisco and the whole band would show up early in the morning and we would sit around with Todd.

I had now written this whole thesis on my idea of the boy who grows up with no real experiences other than what he’s seen on television and had various song titles – T.V. is King, Prime Time, all television related.

So we would sit there of a morning and talk about one of the songs – "OK, we have T.V. is King, let’s talk about that; let’s figure it out" – we would collaborate on the idea behind the song as well as the lyrics and the chord progressions.

We would all sit together in the morning – Bill and Roger with their guitars, Vince with his keyboards and Todd, and work all this out – and we had the tune before noon!

We took a lunch-break, came back to the studio and that afternoon we recorded the song we had just written three hours before!

Bondage and What Do You Want From Life; all three remain staples of the live set. The outstanding Remote Control has an interesting lyrical story and an even more interesting recording story.

RM: Following those Hammersmith dates and the subsequent live album came the Remote Control album and tour of 1979, which included a date at yet another famous UK venue, the sadly long gone Glasgow Apollo.

I believe Remote Control to be the band’s finest hour but I also have to say, as a major Todd Rundgren fan, I love the "Todd Job" on that album – from the production and sound to the song-writing and arrangements.

How did that whole concept and what became, in effect, a collaborative project with Todd come about?

FW: Well, it was an unusual situation, first of all. Including the live album Remote Control was the fifth album we had made for A&M Records, but we had never had a hit.

White Punks On Dope did get rereleased as a single after the live album came out, and it did get some airplay and some attention, but even although we had a five album deal with the record company – which certainly doesn’t happen any more – we had never really sold that many records; we hadn’t had that much radio success.

So the record company came down hard on us for the fifth record. They said "OK, we’re only going to give you this much money and you only have that much time to get a record done."

So we were really under the gun on that one and we really weren’t prepared for that; we didn’t have all the songs written but I did have this idea of the boy who grows up watching television – which I pretty much stole from Jerzy Kosinski and his book called Being There [laughs].

But back then I figured "well, nobody has ever heard of this guy; nobody has ever heard of his book and this is a great idea. I want to morph it and mutate it into music in a Tubes-type style."

I presented the concept to Todd, he said "yeah, ok, that’s a pretty good idea," we all headed for the studio and we ended up writing and recording each song for the album, together, in the same day!

RM: Wow [laughs].

FW: Yeah, that’s how we did it. We booked one month in a little studio just outside of San Francisco and the whole band would show up early in the morning and we would sit around with Todd.

I had now written this whole thesis on my idea of the boy who grows up with no real experiences other than what he’s seen on television and had various song titles – T.V. is King, Prime Time, all television related.

So we would sit there of a morning and talk about one of the songs – "OK, we have T.V. is King, let’s talk about that; let’s figure it out" – we would collaborate on the idea behind the song as well as the lyrics and the chord progressions.

We would all sit together in the morning – Bill and Roger with their guitars, Vince with his keyboards and Todd, and work all this out – and we had the tune before noon!

We took a lunch-break, came back to the studio and that afternoon we recorded the song we had just written three hours before!

RM: That quick-fire writing and recording approach certainly did Remote Control no harm whatsoever…

FW: I think one of the biggest mistakes you can make as a songwriter, or any type of writer, is to second guess yourself – to not go with your original instinct or your gut. But so many people make that mistake.

We call it beat the demo – you make this great demo that’s raw and not over-thought but when you go to record it? You fuck it up!

You try to do this, you try to fix that, you try to make that part better, and then you try doing it another way… you go about eighteen different ways and you end up coming back to the demo!

But you never could beat the demo because the demo was your gut, you know?

So the reason I think Remote Control came out so well was because we didn’t have time to do any of that.

We didn’t have time to second guess ourselves. We wrote the songs in the morning, we recorded them in the afternoon and the next day it was on to the next song!

It wasn’t "let’s go back and fix this and change that" or "maybe if we did this it would be better" or "what if we tried…" Bullshit! [laughs]. We didn’t have the time – "we’ve done that one and now it’s on to the next."

But it was hard. We were at the studio around eighteen hours a day trying to get this record done, but I think the results stand the test of time.

RM: Well as I said earlier I believe it be your strongest work. It’s amazing how many artists or bands will say, years after the event, they should have gone with the demos or at least used the demos as their backing tracks. First thoughts do tend to be the best thoughts…

FW: They really are. It’s one thing to not play the part right – so you go back and play it until you get it right – but in general you’ve got to go with your gut; you’ve got to go with your original instinct.

When I write lyrics or poetry – I’ve been writing poetry lately and have a book of poetry that’s not lyric related but more a stream of consciousness – I try to avoid going back and changing it.

You might start to think "oh if I just change that one word it will be better" but, no – the original thought that came from your gut, or formulated in your brain, without you trying it couch it in some other way, always ends up being the best.

RM: From the success of Remote Control to the complete lack of success – to the extent that it was never released – of what should have been the follow-up album, Suffer For Sound.

Tracks have since been made available on re-released or repackaged Tubes albums and the entire album is out there, albeit unofficially, but what’s interesting is just what a radical departure that album was, or would have been, for The Tubes – guitar-led new wave power pop, with many songs carrying a darker edge.

Your own thoughts?

FW: Well first of all we thought Remote Control was going to put us over the top, but while it did OK, it didn’t do great.

It did do enough for the record company to say "we’re going to give you one more chance" but they wouldn’t come up with a producer for us.

So we have no producer and then the record company says "we’re going to give you just enough money to record the basic tracks – bass, drums, guitar and a scratch vocal – and then we have to approve it."

And, oh my God, at that point everybody just flipped out; that just pissed us off so bad.

But they were adamant; they weren’t going to give us any more money.

So we’re in the studio in San Francisco and there’s a record company guy there saying "OK, I need to send a tape of your bass, drums, guitar and scratch vocal recordings to the record company for approval so they can give you more money to allow you to finish the record, do your overdubs and mix it."

That just pissed everyone off again and when the record company guy asked me to put a scratch vocal on some of the basic tracks, I refused to do it.

I said "No, I’ve got nothing; this sucks and you can’t tell me what to do. If you want to dump us, dump us, I don’t care."

So I didn’t do it but our manager did talk them in to giving us more money so we could finish the record.

But we ended up writing all these negative songs like Don’t Slow Down and Don’t Ask Me; every song had some sort of negative connotation [laughs].

When we presented the record company with the record they said "We don’t like it. It’s too dark and you’ve wasted our money; we don’t want to release it." So they didn’t release it but they did release us [laughs]

"You’re fired. You didn’t make us enough money – you’re gone."

So the record just kind of died away and we’ve never really played a lot from it. Every once in a while we might play something from it – we’re doing Rat Race from that album in the new show – but nobody has ever heard of it and most people just want to hear their favourites being played.

RM: The move from A&M to Capitol and the recording of later albums such as The Completion Backward Principle and Outside Inside certainly helped create a quality batch of 80s favourites to go with the earlier 70s classics…

FW: And that’s what people want to hear – they want their classics. They want What Do You Want From Life, White Punks on Dope, Mondo Bondage, She’s a Beauty, Talk to Ya Later, Mr Hate… we give them what they want to hear.

FW: I think one of the biggest mistakes you can make as a songwriter, or any type of writer, is to second guess yourself – to not go with your original instinct or your gut. But so many people make that mistake.

We call it beat the demo – you make this great demo that’s raw and not over-thought but when you go to record it? You fuck it up!

You try to do this, you try to fix that, you try to make that part better, and then you try doing it another way… you go about eighteen different ways and you end up coming back to the demo!

But you never could beat the demo because the demo was your gut, you know?

So the reason I think Remote Control came out so well was because we didn’t have time to do any of that.

We didn’t have time to second guess ourselves. We wrote the songs in the morning, we recorded them in the afternoon and the next day it was on to the next song!

It wasn’t "let’s go back and fix this and change that" or "maybe if we did this it would be better" or "what if we tried…" Bullshit! [laughs]. We didn’t have the time – "we’ve done that one and now it’s on to the next."

But it was hard. We were at the studio around eighteen hours a day trying to get this record done, but I think the results stand the test of time.

RM: Well as I said earlier I believe it be your strongest work. It’s amazing how many artists or bands will say, years after the event, they should have gone with the demos or at least used the demos as their backing tracks. First thoughts do tend to be the best thoughts…

FW: They really are. It’s one thing to not play the part right – so you go back and play it until you get it right – but in general you’ve got to go with your gut; you’ve got to go with your original instinct.

When I write lyrics or poetry – I’ve been writing poetry lately and have a book of poetry that’s not lyric related but more a stream of consciousness – I try to avoid going back and changing it.

You might start to think "oh if I just change that one word it will be better" but, no – the original thought that came from your gut, or formulated in your brain, without you trying it couch it in some other way, always ends up being the best.

RM: From the success of Remote Control to the complete lack of success – to the extent that it was never released – of what should have been the follow-up album, Suffer For Sound.

Tracks have since been made available on re-released or repackaged Tubes albums and the entire album is out there, albeit unofficially, but what’s interesting is just what a radical departure that album was, or would have been, for The Tubes – guitar-led new wave power pop, with many songs carrying a darker edge.

Your own thoughts?

FW: Well first of all we thought Remote Control was going to put us over the top, but while it did OK, it didn’t do great.

It did do enough for the record company to say "we’re going to give you one more chance" but they wouldn’t come up with a producer for us.

So we have no producer and then the record company says "we’re going to give you just enough money to record the basic tracks – bass, drums, guitar and a scratch vocal – and then we have to approve it."

And, oh my God, at that point everybody just flipped out; that just pissed us off so bad.

But they were adamant; they weren’t going to give us any more money.

So we’re in the studio in San Francisco and there’s a record company guy there saying "OK, I need to send a tape of your bass, drums, guitar and scratch vocal recordings to the record company for approval so they can give you more money to allow you to finish the record, do your overdubs and mix it."

That just pissed everyone off again and when the record company guy asked me to put a scratch vocal on some of the basic tracks, I refused to do it.

I said "No, I’ve got nothing; this sucks and you can’t tell me what to do. If you want to dump us, dump us, I don’t care."

So I didn’t do it but our manager did talk them in to giving us more money so we could finish the record.

But we ended up writing all these negative songs like Don’t Slow Down and Don’t Ask Me; every song had some sort of negative connotation [laughs].

When we presented the record company with the record they said "We don’t like it. It’s too dark and you’ve wasted our money; we don’t want to release it." So they didn’t release it but they did release us [laughs]

"You’re fired. You didn’t make us enough money – you’re gone."

So the record just kind of died away and we’ve never really played a lot from it. Every once in a while we might play something from it – we’re doing Rat Race from that album in the new show – but nobody has ever heard of it and most people just want to hear their favourites being played.

RM: The move from A&M to Capitol and the recording of later albums such as The Completion Backward Principle and Outside Inside certainly helped create a quality batch of 80s favourites to go with the earlier 70s classics…

FW: And that’s what people want to hear – they want their classics. They want What Do You Want From Life, White Punks on Dope, Mondo Bondage, She’s a Beauty, Talk to Ya Later, Mr Hate… we give them what they want to hear.

The Tubes 40 years on, still dressed to theatrically thrill and now happy to play the hits the fans

want to hear. Original members Rick Anderson, Prairie Prince, Fee Waybill and Roger Steen are

joined by keyboardist David Medd (second from right), who has worked with the band since 1996.

RM: For many bands, playing the hits or performing the classics has become the audience demanded, industry standard while any new material tends to struggle.

Talking of which, we have to go back to 1996 for Genius of America, the last all-new studio album from The Tubes and 1997 for your last studio album Don’t Be Scared By These Hands.

I presume one of the issues behind lack of new material is the problem of would people even buy it?

FW: Yeah, absolutely; they don’t care about new material. I don’t care if someone says "there’s a new Berlin album" or "there’s a new Styx album" – they won’t sell, because not enough people care.

They want to hear the hits – they want to hear the songs that helped formulate their childhood; their puberty; their ascension to adulthood.

We had six or seven songs of new material in our set about ten or twelve years ago and nobody cared; they didn’t want to hear that. They looked at us as if to say "wait, what the hell is this? I want to hear White Punks on Dope and She’s a Beauty and Talk to Ya Later."

And record companies know this – they know nobody really cares.

RM: But as a creative artist and songwriter that must be difficult to accept – or has it become a case of C’est La Vie?

FW: Pretty much. We are doing a couple of rarer songs on this show – like I said earlier we’re doing Rat Race from Suffer For Sound – but people still look at us when we play it thinking "what the hell was that about? I’ve never even heard of it."

We’re also doing Life is Pain, which is a great fuckin’ song Roger and I wrote years ago and have played before. And we do them anyway, even though people go "yeah, well, ok... next!" [laughs]

RM: Well I’m delighted they are both in the set. In fact I’d love to hear you say you’re coming over to tour and playing half-a-dozen songs from a forthcoming album, maybe throw in a couple of not-often played album tracks while also peppering the show with some hits… but I’m not your target audience.

FW: No. And that’s just the way it is.

RM: I mentioned your last studio album, Don't Be Scared By These Hands, earlier.

That's one of two great solo albums from you, the other being 1984’s Read My Lips – both feature guitar work from Steve Lukather and songwriting and vocal contributions from Richard Marx.

I'd like to see and hear a third Fee Waybill solo album – but what about Fee Waybill himself?

FW: Personally I would, yes, and I’ve actually been working with Richard Marx on some songs – Richard and I have been working and writing together for years and we've been best friends for more than thirty years.

We've been working on songs for a solo album for a couple of years now and I have about six songs done, so eventually I will come up with another solo record.

Richard just moved out here to Malibu from Chicago; he’s setting up his new house and he’s going to get a little studio and when he does we’ll get back to it and I’ll get it done.

RM: That’s good to hear and as we wrap this up I have to add that I really hope, come the time, it will get some attention because it’s guys like you – happy to perform the hits but also an artist and songwriter that wants to create new material – that deserve to have a market for that material.

FW: Well thank you and I’m really looking forward to playing in Scotland again, believe me I am!

RM: And we’ll be happy to see you; you and the boys are always welcome here.

Fee, thanks for talking Tubes at some length and rather than predictably end by playing Talk To Ya Later we're going to finish with one of your solo tracks – and What's Wrong With That?

FW: [laughs] Cool! And thank you Ross!

want to hear. Original members Rick Anderson, Prairie Prince, Fee Waybill and Roger Steen are

joined by keyboardist David Medd (second from right), who has worked with the band since 1996.

RM: For many bands, playing the hits or performing the classics has become the audience demanded, industry standard while any new material tends to struggle.

Talking of which, we have to go back to 1996 for Genius of America, the last all-new studio album from The Tubes and 1997 for your last studio album Don’t Be Scared By These Hands.

I presume one of the issues behind lack of new material is the problem of would people even buy it?

FW: Yeah, absolutely; they don’t care about new material. I don’t care if someone says "there’s a new Berlin album" or "there’s a new Styx album" – they won’t sell, because not enough people care.

They want to hear the hits – they want to hear the songs that helped formulate their childhood; their puberty; their ascension to adulthood.

We had six or seven songs of new material in our set about ten or twelve years ago and nobody cared; they didn’t want to hear that. They looked at us as if to say "wait, what the hell is this? I want to hear White Punks on Dope and She’s a Beauty and Talk to Ya Later."

And record companies know this – they know nobody really cares.

RM: But as a creative artist and songwriter that must be difficult to accept – or has it become a case of C’est La Vie?

FW: Pretty much. We are doing a couple of rarer songs on this show – like I said earlier we’re doing Rat Race from Suffer For Sound – but people still look at us when we play it thinking "what the hell was that about? I’ve never even heard of it."

We’re also doing Life is Pain, which is a great fuckin’ song Roger and I wrote years ago and have played before. And we do them anyway, even though people go "yeah, well, ok... next!" [laughs]

RM: Well I’m delighted they are both in the set. In fact I’d love to hear you say you’re coming over to tour and playing half-a-dozen songs from a forthcoming album, maybe throw in a couple of not-often played album tracks while also peppering the show with some hits… but I’m not your target audience.

FW: No. And that’s just the way it is.

RM: I mentioned your last studio album, Don't Be Scared By These Hands, earlier.

That's one of two great solo albums from you, the other being 1984’s Read My Lips – both feature guitar work from Steve Lukather and songwriting and vocal contributions from Richard Marx.

I'd like to see and hear a third Fee Waybill solo album – but what about Fee Waybill himself?

FW: Personally I would, yes, and I’ve actually been working with Richard Marx on some songs – Richard and I have been working and writing together for years and we've been best friends for more than thirty years.

We've been working on songs for a solo album for a couple of years now and I have about six songs done, so eventually I will come up with another solo record.

Richard just moved out here to Malibu from Chicago; he’s setting up his new house and he’s going to get a little studio and when he does we’ll get back to it and I’ll get it done.

RM: That’s good to hear and as we wrap this up I have to add that I really hope, come the time, it will get some attention because it’s guys like you – happy to perform the hits but also an artist and songwriter that wants to create new material – that deserve to have a market for that material.

FW: Well thank you and I’m really looking forward to playing in Scotland again, believe me I am!

RM: And we’ll be happy to see you; you and the boys are always welcome here.

Fee, thanks for talking Tubes at some length and rather than predictably end by playing Talk To Ya Later we're going to finish with one of your solo tracks – and What's Wrong With That?

FW: [laughs] Cool! And thank you Ross!

Muirsical Conversation with Fee Waybill

July 2015

The Tubes official website: http://www.thetubes.com/

The Tubes 40th Anniversary UK Tour Dates, 2015:

Bristol, The Fleece - August 3rd

Brighton, Concorde 2 - August 4th

Southampton, The Brook - August 6th

London, Clapham Grand - August 7th

Manchester, Club Academy - August 8th

Glasgow, The Art School - August 9th

Leeds, Brudenell Arts Club - August 11th

Edinburgh, Liquid Rooms - August 12th

Wolverhampton, Robin 2 - August 13th

Photo Credits: Juergen Spachmann (Fee Waybill); Janice Kang (The Tubes)

Audio tracks presented to accompany the above article and to promote the work of the artists.

No infringement of copyright is intended.

July 2015

The Tubes official website: http://www.thetubes.com/

The Tubes 40th Anniversary UK Tour Dates, 2015:

Bristol, The Fleece - August 3rd

Brighton, Concorde 2 - August 4th

Southampton, The Brook - August 6th

London, Clapham Grand - August 7th

Manchester, Club Academy - August 8th

Glasgow, The Art School - August 9th

Leeds, Brudenell Arts Club - August 11th

Edinburgh, Liquid Rooms - August 12th

Wolverhampton, Robin 2 - August 13th

Photo Credits: Juergen Spachmann (Fee Waybill); Janice Kang (The Tubes)

Audio tracks presented to accompany the above article and to promote the work of the artists.

No infringement of copyright is intended.