The Grand Finale

Muirsical Conversation with Dennis DeYoung

Muirsical Conversation with Dennis DeYoung

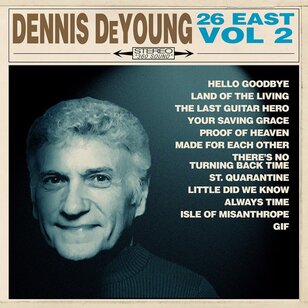

In June of 2021 singer-songwriter-keyboardist and Chicago native Dennis DeYoung released the studio album 26 East Vol 2.

A primarily autobiographical and highly reflective companion piece to 2020’s 26 East Vol 1, the album is also the ex-Styx luminary’s final, recorded work.

Given Dennis DeYoung’s 50 year recording career (from the release of Styx’s self-titled debut album in 1972, through multi-platinum successes with that band and his later solo, theatrical and Music Of Styx Live projects), 26 East Vol 2 is a fitting, half-century later sign-off.

It's also an album that covers all the Dennis DeYoung musical bases, from hard rock, pop-rock and balladeering to rock-gospel, intentionally Styx-esque sounding rock and a poignant 'Grand Finale.'

Dennis DeYoung took time out at home to take a call from FabricationsHQ to discuss the album and some of the lynchpin songs, and their stories, in detail.

Fans and followers of Dennis DeYoung & Styx will also notice the following conversation avoids the usual, latter-day Styx subject and suspects (well documented elsewhere), thus allowing for more positive discussion on topics such as the singer's music theatre projects, solo album One Hundred Years From Now and why having the words "Prog" and "Styx" in the same sentence are still, to this day, akin to waving a red flag at a Chicagoan bull.

But the conversation opened by discussing just how the concept of 26 East came about...

A primarily autobiographical and highly reflective companion piece to 2020’s 26 East Vol 1, the album is also the ex-Styx luminary’s final, recorded work.

Given Dennis DeYoung’s 50 year recording career (from the release of Styx’s self-titled debut album in 1972, through multi-platinum successes with that band and his later solo, theatrical and Music Of Styx Live projects), 26 East Vol 2 is a fitting, half-century later sign-off.

It's also an album that covers all the Dennis DeYoung musical bases, from hard rock, pop-rock and balladeering to rock-gospel, intentionally Styx-esque sounding rock and a poignant 'Grand Finale.'

Dennis DeYoung took time out at home to take a call from FabricationsHQ to discuss the album and some of the lynchpin songs, and their stories, in detail.

Fans and followers of Dennis DeYoung & Styx will also notice the following conversation avoids the usual, latter-day Styx subject and suspects (well documented elsewhere), thus allowing for more positive discussion on topics such as the singer's music theatre projects, solo album One Hundred Years From Now and why having the words "Prog" and "Styx" in the same sentence are still, to this day, akin to waving a red flag at a Chicagoan bull.

But the conversation opened by discussing just how the concept of 26 East came about...

Ross Muir: The seeds were sown for what became 26 East Volumes 1 and 2 not by yourself, I believe, but by your good friend, fellow musician and near neighbour Jim Peterik.

Dennis DeYoung: Yeah, and for all the people out there who have never liked me I’m going to give Jim’s number out to them so they can call him or search him out. [loud laughter]

What you said is all true. Jim and I have known each other a long time and he kept writing me to say "Dennis, the world needs your music" but I told him to have the world text me because I’m not buying it.

But he was relentless; he eventually sent me over a couple of unfinished songs that he thought I might like and said "let’s finish them." So we did finish them and we went on to write nine songs together.

So, yeah, that is how it all happened – I thank him, profusely, for forcing me and shaming me into doing this but I'm not going to give him a dime more in royalties; I swear I won’t! [laughter].

RM: It’s a songwriting partnership that’s paid dividends because through both albums, but more so with Volume 2 in terms of its final act poignancy, I don’t think you could have signed off in better fashion – these are autobiographical, reflective and as I just mentioned quite poignant offerings.

Volume Two also covers every side of you as a singer and songwriter.

DDY: Well first of all thank you for your kind words.

From the very beginning, or once we knew it was going to be two records, I told Jim I wanted them to be concept albums but concept albums that don’t suck, because it’s all about songs and singers for me.

You can have your own personal choices in what you listen to in terms of types of music but for me, if you haven’t got great songs and a decent to great singer? I’m not interested that much.

My trepidation in this whole matter was can I still write some songs, by myself and with Jim, that are worthy of people listening to them and that won’t, in some manner, destroy whatever legacy Styx has, or had, when I was involved with them – you don’t wanna tarnish it by having people say "hey gramps, time for you to retire and move to the beach in Miami!" You don’t want to hear that.

So that drove me to at least write the very best songs that I could, because I know that I can still sing [sings full voice] – "Lady, when you’re with me I’m smiling" – at seventy-four, while sittin’ on the couch [laughter].

But singers need songs, and I think Jim and I did a really good job of writing a collection of good songs on these two albums.

So your kind words are very much appreciated – and as Annie Lennox once sung, who am I to disagree?

RM: [laughs] Well, indeed – never disagree with a Scot, Dennis.

DDY: Oh I know – especially in a tavern…

RM: Steady, laddie [laughter]

You mentioned needing great songs to sing and I want to make special mention here of the album’s bookend tracks, because I don’t think you could have opened and closed the book on your recorded career in any better fashion.

Opener Hello Goodbye is a cleverly constructed musical and lyrical nod to the Beatles, with direct reference to the Fab Four’s massive impact on the US when they performed on the Ed Sullivan show in 1964.

That was a very telling and pivotal moment for a teenage Dennis DeYoung I presume?

DDY: Well the lyric is written from the point of view of the Beatles fan, of which I was one, and all I’m trying to express, or do, is pay homage to the band of all bands – Lennon and McCartney were Adam and Eve and the rest of us were all begat.

But, yes, that night in 1964, as I watched TV, I was transformed and transfixed like so many other musicians of my generation, who knew immediately what they were going to be doing for the rest of their lives – if they could.

And the album title 26 East is, of course, the house where the nucleus of Syx was formed with John and Chuck Panozzo, so my whole mantra has been where it all began – to now, at seventy-four years of age – so shall it end. Hello Goodbye is my bookend to that, and my career, on album.

So, yes, the Beatles changed everything. As I’ve said before, and I really mean it, they were the greatest job creators in the history of the music business; their music spawned entire industries that didn’t exist before they went out and sang and played their music.

So there I was, watching the TV, as a sceptic – because I didn’t like I Wanna Hold Your hand and I still don’t; it was OK but it never made me a Beatles fan – and then I heard [sings] "close your eyes and I’ll miss you…"

I went "Woah! What was that!" It was the sheer joy of what they did.

RM: The other bookend, or more correctly penultimate number Isle of Misanthrope, because there is a short and very familiar finale, is also perfectly placed, given it might just be the greatest song Styx never did.

It also carries a thought-provoking lyric that questions mankind’s actions and where we may be headed.

In review of the album I cited Isle Of Misanthrope as your "Suite Madame Blues for the planet."

DDY: You nailed it, you said it. You absolutely got me, but here’s the funny thing...

When I was doing this record I was trying to be twenty-four years old, in the final analysis. I’m thinking "who was I, at those moments in time, that made me do what I did?" I tried to put myself in that position.

And your comment about the reflective nature of these two volumes is spot on, because old people don’t talk about twenty years from now [laughs]; we talk about things from twenty years earlier!

That’s just how humanity works.

Suite Madame Blue was one of our greatest songs that was completely missed by the record company when Equinox was first released. I think it could have been, dare I say, our Stairway to Heaven, because let’s face it, that’s what I had in mind when I wrote it, I think [laughs].

But, when I went back to listen the old Styx albums – which is something I just don’t do – it dawned on me, when listening to Styx II and a song called Father O.S.A, that, Oh my God, I’d been listening to Court of The Crimson King! [laughs]

So now I’m thinking "hey, Dennis, you thought you were re-writing Suite Madame Blue" but, when I went back and listened to Court of the Crimson King and 21st Century Schizoid man – which, for me, are the two best songs on In the Court of the Crimson King – I thought "that’s Misanthrope!"

So I was going back, in some ways, even further than Equinox and using what I call my fake prog influences because, come on, man, we weren’t a prog band, we were an American rock and roll band.

It's just that we used some of those ideas in our music – and that’s probably what made me write Father O.S.A and Suite Madame Blue in the first place. But, yes, that was all done intentionally on Isle of Misanthrope…

Dennis DeYoung: Yeah, and for all the people out there who have never liked me I’m going to give Jim’s number out to them so they can call him or search him out. [loud laughter]

What you said is all true. Jim and I have known each other a long time and he kept writing me to say "Dennis, the world needs your music" but I told him to have the world text me because I’m not buying it.

But he was relentless; he eventually sent me over a couple of unfinished songs that he thought I might like and said "let’s finish them." So we did finish them and we went on to write nine songs together.

So, yeah, that is how it all happened – I thank him, profusely, for forcing me and shaming me into doing this but I'm not going to give him a dime more in royalties; I swear I won’t! [laughter].

RM: It’s a songwriting partnership that’s paid dividends because through both albums, but more so with Volume 2 in terms of its final act poignancy, I don’t think you could have signed off in better fashion – these are autobiographical, reflective and as I just mentioned quite poignant offerings.

Volume Two also covers every side of you as a singer and songwriter.

DDY: Well first of all thank you for your kind words.

From the very beginning, or once we knew it was going to be two records, I told Jim I wanted them to be concept albums but concept albums that don’t suck, because it’s all about songs and singers for me.

You can have your own personal choices in what you listen to in terms of types of music but for me, if you haven’t got great songs and a decent to great singer? I’m not interested that much.

My trepidation in this whole matter was can I still write some songs, by myself and with Jim, that are worthy of people listening to them and that won’t, in some manner, destroy whatever legacy Styx has, or had, when I was involved with them – you don’t wanna tarnish it by having people say "hey gramps, time for you to retire and move to the beach in Miami!" You don’t want to hear that.

So that drove me to at least write the very best songs that I could, because I know that I can still sing [sings full voice] – "Lady, when you’re with me I’m smiling" – at seventy-four, while sittin’ on the couch [laughter].

But singers need songs, and I think Jim and I did a really good job of writing a collection of good songs on these two albums.

So your kind words are very much appreciated – and as Annie Lennox once sung, who am I to disagree?

RM: [laughs] Well, indeed – never disagree with a Scot, Dennis.

DDY: Oh I know – especially in a tavern…

RM: Steady, laddie [laughter]

You mentioned needing great songs to sing and I want to make special mention here of the album’s bookend tracks, because I don’t think you could have opened and closed the book on your recorded career in any better fashion.

Opener Hello Goodbye is a cleverly constructed musical and lyrical nod to the Beatles, with direct reference to the Fab Four’s massive impact on the US when they performed on the Ed Sullivan show in 1964.

That was a very telling and pivotal moment for a teenage Dennis DeYoung I presume?

DDY: Well the lyric is written from the point of view of the Beatles fan, of which I was one, and all I’m trying to express, or do, is pay homage to the band of all bands – Lennon and McCartney were Adam and Eve and the rest of us were all begat.

But, yes, that night in 1964, as I watched TV, I was transformed and transfixed like so many other musicians of my generation, who knew immediately what they were going to be doing for the rest of their lives – if they could.

And the album title 26 East is, of course, the house where the nucleus of Syx was formed with John and Chuck Panozzo, so my whole mantra has been where it all began – to now, at seventy-four years of age – so shall it end. Hello Goodbye is my bookend to that, and my career, on album.

So, yes, the Beatles changed everything. As I’ve said before, and I really mean it, they were the greatest job creators in the history of the music business; their music spawned entire industries that didn’t exist before they went out and sang and played their music.

So there I was, watching the TV, as a sceptic – because I didn’t like I Wanna Hold Your hand and I still don’t; it was OK but it never made me a Beatles fan – and then I heard [sings] "close your eyes and I’ll miss you…"

I went "Woah! What was that!" It was the sheer joy of what they did.

RM: The other bookend, or more correctly penultimate number Isle of Misanthrope, because there is a short and very familiar finale, is also perfectly placed, given it might just be the greatest song Styx never did.

It also carries a thought-provoking lyric that questions mankind’s actions and where we may be headed.

In review of the album I cited Isle Of Misanthrope as your "Suite Madame Blues for the planet."

DDY: You nailed it, you said it. You absolutely got me, but here’s the funny thing...

When I was doing this record I was trying to be twenty-four years old, in the final analysis. I’m thinking "who was I, at those moments in time, that made me do what I did?" I tried to put myself in that position.

And your comment about the reflective nature of these two volumes is spot on, because old people don’t talk about twenty years from now [laughs]; we talk about things from twenty years earlier!

That’s just how humanity works.

Suite Madame Blue was one of our greatest songs that was completely missed by the record company when Equinox was first released. I think it could have been, dare I say, our Stairway to Heaven, because let’s face it, that’s what I had in mind when I wrote it, I think [laughs].

But, when I went back to listen the old Styx albums – which is something I just don’t do – it dawned on me, when listening to Styx II and a song called Father O.S.A, that, Oh my God, I’d been listening to Court of The Crimson King! [laughs]

So now I’m thinking "hey, Dennis, you thought you were re-writing Suite Madame Blue" but, when I went back and listened to Court of the Crimson King and 21st Century Schizoid man – which, for me, are the two best songs on In the Court of the Crimson King – I thought "that’s Misanthrope!"

So I was going back, in some ways, even further than Equinox and using what I call my fake prog influences because, come on, man, we weren’t a prog band, we were an American rock and roll band.

It's just that we used some of those ideas in our music – and that’s probably what made me write Father O.S.A and Suite Madame Blue in the first place. But, yes, that was all done intentionally on Isle of Misanthrope…

RM: It’s interesting to hear your take on what Styx were, or weren’t, because it parallels what I have always said about Styx and their musical diversity, from rock and roll, hard rock and melodic rock to pop-rock, balladeering, conceptual and theatrical rock.

Styx, for me, weren’t a progressive rock band, they were a rock and roll band with progressive tendencies, or a progressively thinking rock and roll band. If that make sense.

DDY: It does, and here’s the thing about that, which I’ve said over and over again, about Styx being called a prog band.

I have an article in the latest edition of Prog Mag and my name is on the cover, and I think "OK, that’s great," but I never considered myself a prog guy. I was the guy who was the keyboard player, and who would steal ideas I liked and never pay those other guys a dime – to hell with them! [laughter].

I would stick those ideas into Syx music, because we were just trying to create a hybrid – and I think Styx did create a hybrid.

So when the prog snobs, as I call them, and the prog noggins say "oh, Styx, they’re not prog!" I say "I agree with you! Did I say I was? No!" Other people may have said it; I didn’t say it.

We were just a band trying to make the music that we made, but if you want to be an elitist snob about it, I’m right there with ya! [laughter]. We were not a prog band, we were an American rock and roll band.

I mean we had Marshall amplifiers; that shows you weren’t a prog band! [laughs]

RM: But a progressively influenced one, as your Court of the Crimson King comments bear out.

You had six and seven minute songs and the first Styx album opened with Movement For The Common Man, but that was a four-part suite opening and closing with a couple of great rock and roll songs.

Which goes back to your comment about having to have songs, and decent or great singers to sing them.

DDY: And that’s why I wore out on prog. When the proggers become more obsessed with time signatures and their diddling and their doodling and not being so song orientated? That’s when I’ve got no use for them.

I don’t care how good you can play. You think you’re good, then be a jazz musician. If you think you are really good, then play classical music.

I told you the King Crimson songs I liked; with Emerson Lake & Palmer it was Lucky Man and From the Beginning – the songs are what drew me there.

I have to say though Keith Emerson was a great influence on me; I was a huge fan of Keith – I saw ELP and YES very early on, on the same bill, in a theatre in Chicago – can you imagine!

But after watching Keith play for fifteen minutes, you know what I decided? I decided yeah, he can do that, because he’s really good – now where are the songs? Because the songs are it for me.

I get why prog people like that kind of music and I really appreciate the ones that liked us, who thought we were prog-like, but we were just a band who tried to make the best of it as we could.

I think we did a decent job.

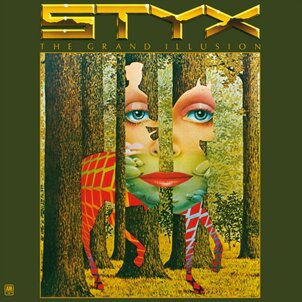

RM: I mentioned earlier that Isle of Misanthrope is actually the penultimate number on 26 East Volume 2 because you finish, fittingly, by revisiting Grand Finale from The Grand Illusion.

A few years back you performed that song each night on the Music Of Styx Grand Illusion 40th Anniversary tour, but I have to tell you the first time I played through 26 East Volume 2, as Grand Finale was reaching its conclusion and you hit the final "we’re all the same" line, I, genuinely, had a lump in my throat.

I was also instantly transported back to 1977. I could vividly hear and see myself playing The Grand Illusion, on my record deck, with what I thought was a really cool four speaker set-up but in reality was just two spare speakers splice-wired to the other two for a double stereo effect [laughs].

Sonic moments in time, four-and-a-half decades apart, yet both as impacting.

DDY: I did that, specifically, because I knew some guy over on the west coast of Scotland would have a lump in his throat [laughter].

Actually, when I did that song, there was a lump in my throat – and I knew, if you think you’re a Styx fan but you don’t have a lump in your throat? Then you’re not a Styx fan.

And my son Matthew got to play on it; Matthew also played drums on Isle of Misanthrope but on Grand Finale he used a ride cymbal given to him by John Panozzo. So for me it has such deep, personal meaning.

RM: All of which makes for the perfect sign-off, because you can’t follow that.

DDY: Yes, and you said it perfectly, when I end by singing the High C on the words "we’re all the same." I had nothing else to say after that. There it is, I’ve said it.

This is what I said, and sung, in 1977 and I haven’t changed my mind; I still feel the same way.

I believe we are all the same and the sooner mankind stops figuring out different ways to find faults in their fellow human beings, for whatever reason – be it colour of skin, language, tradition, culture, religion – the better off we’re going to be.

What I said then I stand by now – deep inside we’re all the same.

RM: Such a simple yet powerful six-word line – when I reviewed 26 East Volume 2 I signed off with those very words.

DDY: That’s because you’re a Styx fan; maybe you destroyed your hearing with those four speakers [laughter] but you were actually looking at and listening to the lyrics, and making sense of them.

A lot of people listen to music and the lyrics are really secondary; they like the way something sounds, and they’re in.

The people who love prog music for example; they – by and large, but not all – don’t care about the lyrics.

Of all the prog albums I owned I think I understood about three of the lyrics [laughs] because a lot of the lyrics are very mystical, or mythical.

Actually you’ll get a kick out of this – you know Jon Anderson, right?

RM: I do indeed.

DDY: Yeah, well I’m working on a song project right now, with Jon; YES were another influence on early Styx. I’m shooting the shit with the guy and I said "Jon, I love your music but what was the meaning of those songs?" [laughs]. But it didn’t matter to me because it had the sound of what I like to listen to.

For many people who like Jon’s music the lyrics are secondary to the sound of it; I can respect that.

But there you are, over in Scotland, with your four speakers in 1977, going "deep inside we’re all the same…

I like this band; they’re saying something that means something."

RM: Purposeful or meaningful lyricism is reflected right across 26 East Volume 2 including another song I wanted to make mention of, The Last Guitar Hero, which features Tom Morello.

Like All Due Respect on 26 East Volume 1 – another great song – you’re making a current and telling social commentary, in this case about the plight of the musician in what is a greedy and unbalanced music industry.

DDY: I would like all musicians to hear that song, but especially the younger guys who can’t make a dime in this business any more.

Actually I take that back, they can get a dime, but that's it, because [quotes the lyric] "the music plays for free tonight from the corporate parasites, living off the blood of their creators – the player stands there all alone, shreds his fingers to the bone, everywhere he looks nothing but traitors."

That’s what’s happened and here’s the problem for the audience...

Number one is the definition of a shmuck – someone who pays for something they can get for free.

If there’s a radial tyres store right there selling tyres for free, and a radial tyres store right next door selling tyres for seven hundred dollars, we know where people are going, right?

And this is what’s happening to music; you can’t stop people listening to music for free and that’s just so crushing – at some point, if this continues, it’s going to stop some people from being musicians who thought they could actually make a living.

Not everyone has to be a millionaire, but you gotta pay something for what people create.

RM: Of course you do – or should. It’s both an artistic creation and a livelihood.

The other side of the same coin, and this is something I’ve said on many an occasion in such discussions and arguments, is that, sadly, songwriting and music is no longer being seen or heard as a form of artistry.

It’s being devalued to the degree that musical creativity has been replaced by marketable commodity.

DDY: What I think, and this points to where a lot of pop music has gone, is it’s mostly in the hands of producers and less in the hands of those from the glory days of pop and rock music, starting with the Beatles, where bands were self-contained.

They came up with the songs, they played, they sang, they could have a producer – look what George Martin did for the Beatles – but it wasn’t ever a dictatorship as it has now become for most of the pop stars of today.

As I say in The Last Guitar Hero "why should anybody care – he’s the last guitar hero, with pretty pop stars everywhere..."

Styx, for me, weren’t a progressive rock band, they were a rock and roll band with progressive tendencies, or a progressively thinking rock and roll band. If that make sense.

DDY: It does, and here’s the thing about that, which I’ve said over and over again, about Styx being called a prog band.

I have an article in the latest edition of Prog Mag and my name is on the cover, and I think "OK, that’s great," but I never considered myself a prog guy. I was the guy who was the keyboard player, and who would steal ideas I liked and never pay those other guys a dime – to hell with them! [laughter].

I would stick those ideas into Syx music, because we were just trying to create a hybrid – and I think Styx did create a hybrid.

So when the prog snobs, as I call them, and the prog noggins say "oh, Styx, they’re not prog!" I say "I agree with you! Did I say I was? No!" Other people may have said it; I didn’t say it.

We were just a band trying to make the music that we made, but if you want to be an elitist snob about it, I’m right there with ya! [laughter]. We were not a prog band, we were an American rock and roll band.

I mean we had Marshall amplifiers; that shows you weren’t a prog band! [laughs]

RM: But a progressively influenced one, as your Court of the Crimson King comments bear out.

You had six and seven minute songs and the first Styx album opened with Movement For The Common Man, but that was a four-part suite opening and closing with a couple of great rock and roll songs.

Which goes back to your comment about having to have songs, and decent or great singers to sing them.

DDY: And that’s why I wore out on prog. When the proggers become more obsessed with time signatures and their diddling and their doodling and not being so song orientated? That’s when I’ve got no use for them.

I don’t care how good you can play. You think you’re good, then be a jazz musician. If you think you are really good, then play classical music.

I told you the King Crimson songs I liked; with Emerson Lake & Palmer it was Lucky Man and From the Beginning – the songs are what drew me there.

I have to say though Keith Emerson was a great influence on me; I was a huge fan of Keith – I saw ELP and YES very early on, on the same bill, in a theatre in Chicago – can you imagine!

But after watching Keith play for fifteen minutes, you know what I decided? I decided yeah, he can do that, because he’s really good – now where are the songs? Because the songs are it for me.

I get why prog people like that kind of music and I really appreciate the ones that liked us, who thought we were prog-like, but we were just a band who tried to make the best of it as we could.

I think we did a decent job.

RM: I mentioned earlier that Isle of Misanthrope is actually the penultimate number on 26 East Volume 2 because you finish, fittingly, by revisiting Grand Finale from The Grand Illusion.

A few years back you performed that song each night on the Music Of Styx Grand Illusion 40th Anniversary tour, but I have to tell you the first time I played through 26 East Volume 2, as Grand Finale was reaching its conclusion and you hit the final "we’re all the same" line, I, genuinely, had a lump in my throat.

I was also instantly transported back to 1977. I could vividly hear and see myself playing The Grand Illusion, on my record deck, with what I thought was a really cool four speaker set-up but in reality was just two spare speakers splice-wired to the other two for a double stereo effect [laughs].

Sonic moments in time, four-and-a-half decades apart, yet both as impacting.

DDY: I did that, specifically, because I knew some guy over on the west coast of Scotland would have a lump in his throat [laughter].

Actually, when I did that song, there was a lump in my throat – and I knew, if you think you’re a Styx fan but you don’t have a lump in your throat? Then you’re not a Styx fan.

And my son Matthew got to play on it; Matthew also played drums on Isle of Misanthrope but on Grand Finale he used a ride cymbal given to him by John Panozzo. So for me it has such deep, personal meaning.

RM: All of which makes for the perfect sign-off, because you can’t follow that.

DDY: Yes, and you said it perfectly, when I end by singing the High C on the words "we’re all the same." I had nothing else to say after that. There it is, I’ve said it.

This is what I said, and sung, in 1977 and I haven’t changed my mind; I still feel the same way.

I believe we are all the same and the sooner mankind stops figuring out different ways to find faults in their fellow human beings, for whatever reason – be it colour of skin, language, tradition, culture, religion – the better off we’re going to be.

What I said then I stand by now – deep inside we’re all the same.

RM: Such a simple yet powerful six-word line – when I reviewed 26 East Volume 2 I signed off with those very words.

DDY: That’s because you’re a Styx fan; maybe you destroyed your hearing with those four speakers [laughter] but you were actually looking at and listening to the lyrics, and making sense of them.

A lot of people listen to music and the lyrics are really secondary; they like the way something sounds, and they’re in.

The people who love prog music for example; they – by and large, but not all – don’t care about the lyrics.

Of all the prog albums I owned I think I understood about three of the lyrics [laughs] because a lot of the lyrics are very mystical, or mythical.

Actually you’ll get a kick out of this – you know Jon Anderson, right?

RM: I do indeed.

DDY: Yeah, well I’m working on a song project right now, with Jon; YES were another influence on early Styx. I’m shooting the shit with the guy and I said "Jon, I love your music but what was the meaning of those songs?" [laughs]. But it didn’t matter to me because it had the sound of what I like to listen to.

For many people who like Jon’s music the lyrics are secondary to the sound of it; I can respect that.

But there you are, over in Scotland, with your four speakers in 1977, going "deep inside we’re all the same…

I like this band; they’re saying something that means something."

RM: Purposeful or meaningful lyricism is reflected right across 26 East Volume 2 including another song I wanted to make mention of, The Last Guitar Hero, which features Tom Morello.

Like All Due Respect on 26 East Volume 1 – another great song – you’re making a current and telling social commentary, in this case about the plight of the musician in what is a greedy and unbalanced music industry.

DDY: I would like all musicians to hear that song, but especially the younger guys who can’t make a dime in this business any more.

Actually I take that back, they can get a dime, but that's it, because [quotes the lyric] "the music plays for free tonight from the corporate parasites, living off the blood of their creators – the player stands there all alone, shreds his fingers to the bone, everywhere he looks nothing but traitors."

That’s what’s happened and here’s the problem for the audience...

Number one is the definition of a shmuck – someone who pays for something they can get for free.

If there’s a radial tyres store right there selling tyres for free, and a radial tyres store right next door selling tyres for seven hundred dollars, we know where people are going, right?

And this is what’s happening to music; you can’t stop people listening to music for free and that’s just so crushing – at some point, if this continues, it’s going to stop some people from being musicians who thought they could actually make a living.

Not everyone has to be a millionaire, but you gotta pay something for what people create.

RM: Of course you do – or should. It’s both an artistic creation and a livelihood.

The other side of the same coin, and this is something I’ve said on many an occasion in such discussions and arguments, is that, sadly, songwriting and music is no longer being seen or heard as a form of artistry.

It’s being devalued to the degree that musical creativity has been replaced by marketable commodity.

DDY: What I think, and this points to where a lot of pop music has gone, is it’s mostly in the hands of producers and less in the hands of those from the glory days of pop and rock music, starting with the Beatles, where bands were self-contained.

They came up with the songs, they played, they sang, they could have a producer – look what George Martin did for the Beatles – but it wasn’t ever a dictatorship as it has now become for most of the pop stars of today.

As I say in The Last Guitar Hero "why should anybody care – he’s the last guitar hero, with pretty pop stars everywhere..."

DDY: That song is about so much more, in my mind, than has happened to musicians; it's how I explain what is happening to all humankind, because they’ll be coming for you next.

Technology, with its ever-expanding role at a rate of speed we can’t comprehend, is going to change human life and human beings. It’s a theme I started with Mr Roboto when I wrote that song back in 1982.

We really have to make a bargain, don’t we, with the technologies we create – The Last Guitar Hero is the musical example of that, of what could hit us all, right where we live – "they’re working hard, you know it’s true, to find an app to replace you!"

RM: Your comments parallel a great quote usually, quite incorrectly, assigned to Albert Einstein but that actually comes from Jeff Goldblum’s character in the 1990s movie Powder.

To paraphrase – It’s becoming clear our technology has surpassed our humanity.

DDY: Yeah, but we created it! All these machines wouldn’t exist without our brains to create them.

Human beings are so flawed and some of us are a real piece of work – that’s becoming even clearer with the pandemic and Social Media, where we see very clearly how people think, act and feel.

But that ability to be so flawed, and think the way we think, is important to what humanity is all about.

So, yes, we should all be in fear of that technology surpassing humanity because we’re losing control of it.

It’s, as I like to say, all the little smarty pants and younger people inventing this stuff, like Mark Marky Zuckerberg – my favourite guy [laughter].

His mission statement was that he wants to connect everyone, to which I say did you meet everyone?

Are you kidding me?

The naivety of that is beyond belief – and now we see it as not so much Social Media but Anti-Social Media, which is what most of it is.

RM: Anti-Social Media is the perfect summation; there’s very few of us who haven’t been victim to it, for the most ridiculous and trivial of reasons.

DDY: Yeah, and people can go on anonymously and shoot their big mouths off, if they just own a phone! They can say anything they want under a cloak of anonymity.

You know what I say to that? Bring back the fist fight! Used to be If you were in a pub and someone opened their big mouth you might just find there’s somebody who wants to punch it.

But now, you, me or anybody else can say anything we like, under the cloak of darkness, while expressing the vilest parts of human nature.

RM: The only problem with the fist fight solution Dennis is, of course, that these are the very people you will never see face to face; they are only brave behind a screen, or on a keyboard.

DDY: I know! And you look at the even bigger picture and the disruption some hackers can cause to the infrastructure of entire countries. The jackwagons' who say that they hate you? That’s too small.

I’m worried about the bigger jackwagon who is sitting someplace, getting ready to harm millions of people, in ways they can’t even understand, and yet we have no way, quite frankly, to put ‘em in front of a firing squad. That's what we should do; I truly believe that.

RM: Well, that escalated quickly [laughs]

DDY: Yeah, from fist fights to public executions! [laughs].

But, the damage they do, or can do, shows human beings have too much power – some have more power in a small device in their hands than the Kings of Scotland had in the seventeenth century!

RM: Well, I’m not going to go back as far as the seventeenth century [laughs] but I do want to take you back to the 1990s.

Given the not insignificant musical, and by association label, changes as the 80s became the 90s it’s perhaps no surprise the first Styx reunion with Glen Burtnik in the fold was, sadly, relatively short lived – although it did produce the highly under-rated Edge of the Century album and very successful single Show Me the Way.

However the rest of that decade was one of your most creative and interesting through your musical theatre work, starting with a role in a touring production of Jesus Christ Superstar.

DDY: I have to tell you all that theatre stuff just kinda happened to me, quite by accident.

My entre into musical theatre was through my brother-in-law Forbes Candlish, a prog nut and whose parents were born and raised in Scotland!

Forbes was the executive producer of Jesus Christ Superstar; he wanted me to play the part of Pontius Pilate.

I said "Forbes, every six months or so you should empty your pond water – what the hell are you talking about?" [laughter].

But he convinced me to do it and from there everything just kinda fell in to place.

RM: So this wasn’t a calling or next step on your part; you were simply accepting an offer of a role?

DDY: Yeah. I honestly never aspired, not one time in my life, to have anything to do with musical theatre, other than taking some elements of it and putting them into the Styx show, which is kinda how I treated prog music.

Let's steal some ideas and see if they fit! [laughs]. I’m the great sponge – I like that, let’s use it!

So I had never pursued anything about Broadway music in my life to that point – I wanted to be in the Beatles!

I didn’t want to be Stephen Sondheim, I wanted to be Paul McCartney!

RM: That’s interesting because right from some of the earliest Styx songs, such as your bawdy lyrical delivery on Grove of Eglantine and the scene-setting style as presented on the opening of Pieces of Eight, to name but two, I was already thinking this is a singer who could easily do, or move on to, musical theatre.

There’s a very theatrical tone and understanding to how you lyricise and vocally emphasise, as evidenced on your 1994 solo album Ten On Broadway.

DDY: Well I’m not going to disagree with you because you know what, I guess I am suited to musical theatre.

I think I’m a decent enough singer to do that kind of stuff but that’s not going to stop me rocking out to Isle of Misanthrope! [laughs]

I’ve never really created an album that I like to listen to, but I can listen to Ten On Broadway start to finish because I can say "well, I never thought I could do that, but I did do that."

I was involved in the album’s creation and the arrangements but really it was about those great songs that I got to interpret; that was the real joy for me.

Technology, with its ever-expanding role at a rate of speed we can’t comprehend, is going to change human life and human beings. It’s a theme I started with Mr Roboto when I wrote that song back in 1982.

We really have to make a bargain, don’t we, with the technologies we create – The Last Guitar Hero is the musical example of that, of what could hit us all, right where we live – "they’re working hard, you know it’s true, to find an app to replace you!"

RM: Your comments parallel a great quote usually, quite incorrectly, assigned to Albert Einstein but that actually comes from Jeff Goldblum’s character in the 1990s movie Powder.

To paraphrase – It’s becoming clear our technology has surpassed our humanity.

DDY: Yeah, but we created it! All these machines wouldn’t exist without our brains to create them.

Human beings are so flawed and some of us are a real piece of work – that’s becoming even clearer with the pandemic and Social Media, where we see very clearly how people think, act and feel.

But that ability to be so flawed, and think the way we think, is important to what humanity is all about.

So, yes, we should all be in fear of that technology surpassing humanity because we’re losing control of it.

It’s, as I like to say, all the little smarty pants and younger people inventing this stuff, like Mark Marky Zuckerberg – my favourite guy [laughter].

His mission statement was that he wants to connect everyone, to which I say did you meet everyone?

Are you kidding me?

The naivety of that is beyond belief – and now we see it as not so much Social Media but Anti-Social Media, which is what most of it is.

RM: Anti-Social Media is the perfect summation; there’s very few of us who haven’t been victim to it, for the most ridiculous and trivial of reasons.

DDY: Yeah, and people can go on anonymously and shoot their big mouths off, if they just own a phone! They can say anything they want under a cloak of anonymity.

You know what I say to that? Bring back the fist fight! Used to be If you were in a pub and someone opened their big mouth you might just find there’s somebody who wants to punch it.

But now, you, me or anybody else can say anything we like, under the cloak of darkness, while expressing the vilest parts of human nature.

RM: The only problem with the fist fight solution Dennis is, of course, that these are the very people you will never see face to face; they are only brave behind a screen, or on a keyboard.

DDY: I know! And you look at the even bigger picture and the disruption some hackers can cause to the infrastructure of entire countries. The jackwagons' who say that they hate you? That’s too small.

I’m worried about the bigger jackwagon who is sitting someplace, getting ready to harm millions of people, in ways they can’t even understand, and yet we have no way, quite frankly, to put ‘em in front of a firing squad. That's what we should do; I truly believe that.

RM: Well, that escalated quickly [laughs]

DDY: Yeah, from fist fights to public executions! [laughs].

But, the damage they do, or can do, shows human beings have too much power – some have more power in a small device in their hands than the Kings of Scotland had in the seventeenth century!

RM: Well, I’m not going to go back as far as the seventeenth century [laughs] but I do want to take you back to the 1990s.

Given the not insignificant musical, and by association label, changes as the 80s became the 90s it’s perhaps no surprise the first Styx reunion with Glen Burtnik in the fold was, sadly, relatively short lived – although it did produce the highly under-rated Edge of the Century album and very successful single Show Me the Way.

However the rest of that decade was one of your most creative and interesting through your musical theatre work, starting with a role in a touring production of Jesus Christ Superstar.

DDY: I have to tell you all that theatre stuff just kinda happened to me, quite by accident.

My entre into musical theatre was through my brother-in-law Forbes Candlish, a prog nut and whose parents were born and raised in Scotland!

Forbes was the executive producer of Jesus Christ Superstar; he wanted me to play the part of Pontius Pilate.

I said "Forbes, every six months or so you should empty your pond water – what the hell are you talking about?" [laughter].

But he convinced me to do it and from there everything just kinda fell in to place.

RM: So this wasn’t a calling or next step on your part; you were simply accepting an offer of a role?

DDY: Yeah. I honestly never aspired, not one time in my life, to have anything to do with musical theatre, other than taking some elements of it and putting them into the Styx show, which is kinda how I treated prog music.

Let's steal some ideas and see if they fit! [laughs]. I’m the great sponge – I like that, let’s use it!

So I had never pursued anything about Broadway music in my life to that point – I wanted to be in the Beatles!

I didn’t want to be Stephen Sondheim, I wanted to be Paul McCartney!

RM: That’s interesting because right from some of the earliest Styx songs, such as your bawdy lyrical delivery on Grove of Eglantine and the scene-setting style as presented on the opening of Pieces of Eight, to name but two, I was already thinking this is a singer who could easily do, or move on to, musical theatre.

There’s a very theatrical tone and understanding to how you lyricise and vocally emphasise, as evidenced on your 1994 solo album Ten On Broadway.

DDY: Well I’m not going to disagree with you because you know what, I guess I am suited to musical theatre.

I think I’m a decent enough singer to do that kind of stuff but that’s not going to stop me rocking out to Isle of Misanthrope! [laughs]

I’ve never really created an album that I like to listen to, but I can listen to Ten On Broadway start to finish because I can say "well, I never thought I could do that, but I did do that."

I was involved in the album’s creation and the arrangements but really it was about those great songs that I got to interpret; that was the real joy for me.

RM: That dip into some of the iconic Broadway songs paved the way for your own musical based on The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which played the Tennessee Performing Arts Center in 1997 and won a Best Musical in Chicago award when it played your hometown in 2008.

DDY: And Hunchback is going to close the Skylight Theater’s season, in Milwaukee, in June of 2022.

It was supposed to open their season last September but I read periodically about some bug that’s going around? [laughter]

As I’ve said about myself before I’m a melody man. As a singer, I can rock if you need me to but as a songwriter I’m probably better – actually I know I’m better – at writing the grand melody, which lends itself to writing songs for Broadway musicals.

So I took a shot at it with Hunchback and I’ve had some success with it but, there is no greater joy for me than being in a rock and roll band, with your own music, playing in front of an enthusiastic rock audience.

I was talking to Henry Mancini one time back then about scoring music and he said "man, don’t score music, you’ve got the best job in the world!"

Everybody wants to be, or wanted to be, a rock star, and I had that job.

RM: And still have, backed by a great live band that collectively deliver The Music Of Styx and Dennis DeYoung.

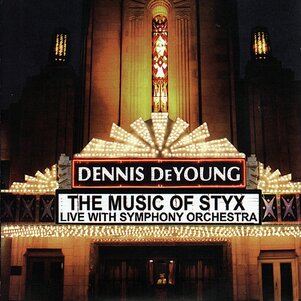

Talking of Styx music and the big hitters from the repertoire, were you aware when writing the likes of Suite Madame Blue, Castle Walls, The Grand Illusion et al, that they would lend themselves so well to orchestration, as borne out by the Music Of Styx with Symphony Orchestra performances and later 2004 live album?

DDY: Back then, when I wrote those songs, I think I was just looking for colours.

It's the keyboard player's job, in bands like Styx, to introduce the colours the guitarist can’t – because we all know rock music is the purview of guitar players.

When I was writing those songs, and playing my keyboard parts, I only really saw myself as the guy using whatever technology was around at the time to add those colours – "hey, look, here’s a string machine synthesizer, and here’s a mellotron, let’s use that!"

So I was simply trying to find the gadgets, and parts, to create something and use them to their best ability in any Styx song, just to give them something before, you know, here come the guitars again! [laughs].

That’s really how I viewed it; I couldn’t tell you I was precious enough to think someday we’d be orchestrating this stuff.

RM: Making it all the more of a thrill when you did get the chance to have them scored for orchestration all these decades later, in live performance.

Some of those songs are incredibly vibrant, and carry quite a bit of majesty, with a full orchestra behind them.

DDY: Yeah, I loved doing those shows; we did a lot of them.

Too many orchestra shows with rock bands are just string players playing behind rock guys; to the degree that you can’t even hear the orchestra; it’s not really part of it.

My idea was to absolutely bring the two together and incorporate the orchestra into the Styx songs, which worked out really nicely for me because I’m a guy that studied accordion, and accordion players also studied classical music – they didn’t all play polka!

When I was growing up and learning, I played a lot of the classics, transposed for accordion – now that’s probably not your idea of a great night out [loud laughter], and I wouldn’t recommend it, but it was essential for accordion players!

RM: I'd like to finish by giving a shout out to your 2007 solo album, One Hundred Years From Now, which many a fan and critic describe as your solo Styx album.

It also has a lyrically profound and musically powerful title track, which features you in duet, and dual language, with Canadian francophone singer Éric Lapointe.

DDY: When people go on about 26 East Volume 1 and now Volume 2, I have to tell you that, if I put my hand on the Bible and tell you the truth, I don’t think they’re any better than One Hundred Years From Now.

The problem was no-one really knew it existed outside of Canada, where we had a record deal and a number one record; I love all the songs on One Hundred Years From Now, bar none.

RM: That's why I wanted to mention it because it deserves the recognition it never got first time around, nor on its unheralded 2009 US release.

I mentioned the title track; how did that duet with Éric come about, because you are very different singers yet the results are a strong, vocal dovetailing.

DDY: Well it took a lot of mixing on my part to bring those two voices together, I can tell you that! [laughter]

My good friend Paul Jessop, who was head of promotion at Universal Music, said to me "listen I think you should do a duet; here's some names but I think this guy Éric Lapoint would be cool – if you think you could make that happen."

He asked ne if I thought I could make our voices work and I said yes, I thought I could – the idea that our voices were so different is what I thought would make it interesting.

I talked to Éric and sent him the lyrics, in English, which he translated into French; he then came over to my house, on my sixtieth birthday, to do the vocals down here at my studio.

It turned out to be really good and we had a number one record in Quebec, which was pretty cool, but I have to tell you the strongest song on that album for me is Crossing the Rubicon...

DDY: And Hunchback is going to close the Skylight Theater’s season, in Milwaukee, in June of 2022.

It was supposed to open their season last September but I read periodically about some bug that’s going around? [laughter]

As I’ve said about myself before I’m a melody man. As a singer, I can rock if you need me to but as a songwriter I’m probably better – actually I know I’m better – at writing the grand melody, which lends itself to writing songs for Broadway musicals.

So I took a shot at it with Hunchback and I’ve had some success with it but, there is no greater joy for me than being in a rock and roll band, with your own music, playing in front of an enthusiastic rock audience.

I was talking to Henry Mancini one time back then about scoring music and he said "man, don’t score music, you’ve got the best job in the world!"

Everybody wants to be, or wanted to be, a rock star, and I had that job.

RM: And still have, backed by a great live band that collectively deliver The Music Of Styx and Dennis DeYoung.

Talking of Styx music and the big hitters from the repertoire, were you aware when writing the likes of Suite Madame Blue, Castle Walls, The Grand Illusion et al, that they would lend themselves so well to orchestration, as borne out by the Music Of Styx with Symphony Orchestra performances and later 2004 live album?

DDY: Back then, when I wrote those songs, I think I was just looking for colours.

It's the keyboard player's job, in bands like Styx, to introduce the colours the guitarist can’t – because we all know rock music is the purview of guitar players.

When I was writing those songs, and playing my keyboard parts, I only really saw myself as the guy using whatever technology was around at the time to add those colours – "hey, look, here’s a string machine synthesizer, and here’s a mellotron, let’s use that!"

So I was simply trying to find the gadgets, and parts, to create something and use them to their best ability in any Styx song, just to give them something before, you know, here come the guitars again! [laughs].

That’s really how I viewed it; I couldn’t tell you I was precious enough to think someday we’d be orchestrating this stuff.

RM: Making it all the more of a thrill when you did get the chance to have them scored for orchestration all these decades later, in live performance.

Some of those songs are incredibly vibrant, and carry quite a bit of majesty, with a full orchestra behind them.

DDY: Yeah, I loved doing those shows; we did a lot of them.

Too many orchestra shows with rock bands are just string players playing behind rock guys; to the degree that you can’t even hear the orchestra; it’s not really part of it.

My idea was to absolutely bring the two together and incorporate the orchestra into the Styx songs, which worked out really nicely for me because I’m a guy that studied accordion, and accordion players also studied classical music – they didn’t all play polka!

When I was growing up and learning, I played a lot of the classics, transposed for accordion – now that’s probably not your idea of a great night out [loud laughter], and I wouldn’t recommend it, but it was essential for accordion players!

RM: I'd like to finish by giving a shout out to your 2007 solo album, One Hundred Years From Now, which many a fan and critic describe as your solo Styx album.

It also has a lyrically profound and musically powerful title track, which features you in duet, and dual language, with Canadian francophone singer Éric Lapointe.

DDY: When people go on about 26 East Volume 1 and now Volume 2, I have to tell you that, if I put my hand on the Bible and tell you the truth, I don’t think they’re any better than One Hundred Years From Now.

The problem was no-one really knew it existed outside of Canada, where we had a record deal and a number one record; I love all the songs on One Hundred Years From Now, bar none.

RM: That's why I wanted to mention it because it deserves the recognition it never got first time around, nor on its unheralded 2009 US release.

I mentioned the title track; how did that duet with Éric come about, because you are very different singers yet the results are a strong, vocal dovetailing.

DDY: Well it took a lot of mixing on my part to bring those two voices together, I can tell you that! [laughter]

My good friend Paul Jessop, who was head of promotion at Universal Music, said to me "listen I think you should do a duet; here's some names but I think this guy Éric Lapoint would be cool – if you think you could make that happen."

He asked ne if I thought I could make our voices work and I said yes, I thought I could – the idea that our voices were so different is what I thought would make it interesting.

I talked to Éric and sent him the lyrics, in English, which he translated into French; he then came over to my house, on my sixtieth birthday, to do the vocals down here at my studio.

It turned out to be really good and we had a number one record in Quebec, which was pretty cool, but I have to tell you the strongest song on that album for me is Crossing the Rubicon...

RM: Songs such as Crossing the Rubicon help make One Hundred Years From Now the excellent album it is.

In fact, it’s your defining rock statement outside of Styx; it deserved far more traffic and far more success than it got.

DDY: Yeah I think on that album the songwriting and the lyric writing all came together; I hear a song like Crossing the Rubicon and I think "hey, nice going kid!"

You could take Rubicon and One Hundred Years From Now from that album, A Kingdom Ablaze from the first 26 East record and Isle of Misanthrope from Volume 2 – and if that doesn’t tell you who the truest prog influenced guy in the band was I don’t know what else to do! [laughter]

I have to tell you, again in all honesty, those first three solo albums I did in the eighties, were me trying not to be anything like Styx, because I still believed Tommy Shaw would come back to the band when he got himself straightened out and we would continue.

That’s why those three records were more pop and more pc, because, what, I was suddenly going to become Metallica?

But these last three records were more about realising back in 2007, when my wife Suzanne said "did you notice you’re not in Styx anymore?" me going "oh yeah, right; to hell with that, this is what I do."

RM: I still have a real soft spot for Desert Moon but to reciprocate the honesty I have to say that, for me, the second and third albums – albeit they produced a few impressive and poignant numbers such as Black Wall and Harry’s Hands – were diminishing returns cut from the same pop-rock mould.

These last three albums? Far superior, in every way.

DDY: Well, again [sings] "who am I to disagree?"

RM: [laughs] You know that’s not a bad Annie Lennox impression.

DDY: Yeah [laughs]. Annie Lennox is a great singer; isn’t she of Scottish descent?

RM: Scottish through and through.

DDY: And Dave Stewart… Stewart is a Scottish name, isn’t it?

RM: Very much so, but Dave isn’t Scottish – we have tried to claim him, though [laughter]

DDY: Now, who do you think my favourite Scottish singer is?

RM: Well, I don’t think it will be a usual suspect like Rod Stewart; I would say Frankie Miller, but that’s not really in your wheelhouse. Do tell…

DDY: Bon Scott.

RM: Really? That’s great to hear; Bon’s been gone these last four decades and more but what a legacy he left, and helped establish. It’s great to hear someone like yourself giving him the vocal nod.

DDY: Yeah; AC/DC backed us up a couple of times when they first came to the States. I remember looking at Bon and thinking "well, that guy can sing but I wish he’d put down the case of whisky!"

He was literally drinking it down on stage each night. And I loved Jack Bruce, too.

RM: Can’t think of a better way to sign off than with a Chicago rock 'n' roll and Broadway boy talking about great Scottish singers.

Dennis, thank you for spending so much time with FabricationsHQ; this has been a lot of fun, and a pleasure.

DDY: This has been really nice, and I truly appreciate all the kind words because, Ross… deep inside we’re all the same!

In fact, it’s your defining rock statement outside of Styx; it deserved far more traffic and far more success than it got.

DDY: Yeah I think on that album the songwriting and the lyric writing all came together; I hear a song like Crossing the Rubicon and I think "hey, nice going kid!"

You could take Rubicon and One Hundred Years From Now from that album, A Kingdom Ablaze from the first 26 East record and Isle of Misanthrope from Volume 2 – and if that doesn’t tell you who the truest prog influenced guy in the band was I don’t know what else to do! [laughter]

I have to tell you, again in all honesty, those first three solo albums I did in the eighties, were me trying not to be anything like Styx, because I still believed Tommy Shaw would come back to the band when he got himself straightened out and we would continue.

That’s why those three records were more pop and more pc, because, what, I was suddenly going to become Metallica?

But these last three records were more about realising back in 2007, when my wife Suzanne said "did you notice you’re not in Styx anymore?" me going "oh yeah, right; to hell with that, this is what I do."

RM: I still have a real soft spot for Desert Moon but to reciprocate the honesty I have to say that, for me, the second and third albums – albeit they produced a few impressive and poignant numbers such as Black Wall and Harry’s Hands – were diminishing returns cut from the same pop-rock mould.

These last three albums? Far superior, in every way.

DDY: Well, again [sings] "who am I to disagree?"

RM: [laughs] You know that’s not a bad Annie Lennox impression.

DDY: Yeah [laughs]. Annie Lennox is a great singer; isn’t she of Scottish descent?

RM: Scottish through and through.

DDY: And Dave Stewart… Stewart is a Scottish name, isn’t it?

RM: Very much so, but Dave isn’t Scottish – we have tried to claim him, though [laughter]

DDY: Now, who do you think my favourite Scottish singer is?

RM: Well, I don’t think it will be a usual suspect like Rod Stewart; I would say Frankie Miller, but that’s not really in your wheelhouse. Do tell…

DDY: Bon Scott.

RM: Really? That’s great to hear; Bon’s been gone these last four decades and more but what a legacy he left, and helped establish. It’s great to hear someone like yourself giving him the vocal nod.

DDY: Yeah; AC/DC backed us up a couple of times when they first came to the States. I remember looking at Bon and thinking "well, that guy can sing but I wish he’d put down the case of whisky!"

He was literally drinking it down on stage each night. And I loved Jack Bruce, too.

RM: Can’t think of a better way to sign off than with a Chicago rock 'n' roll and Broadway boy talking about great Scottish singers.

Dennis, thank you for spending so much time with FabricationsHQ; this has been a lot of fun, and a pleasure.

DDY: This has been really nice, and I truly appreciate all the kind words because, Ross… deep inside we’re all the same!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Dennis DeYoung

June 2021

26 East Vol 2 is available on Frontiers Records.

(Click here for FabricationsHQ's review of 26 East Volume 2)

Official Dennis DeYoung website: http://www.dennisdeyoung.com

Photo Credits:

Official Press Photo (topmost image)

Vera Harder Photography (DDY with Kilroy mask)

Muirsical Conversation with Dennis DeYoung

June 2021

26 East Vol 2 is available on Frontiers Records.

(Click here for FabricationsHQ's review of 26 East Volume 2)

Official Dennis DeYoung website: http://www.dennisdeyoung.com

Photo Credits:

Official Press Photo (topmost image)

Vera Harder Photography (DDY with Kilroy mask)