Singing the language's praises

Muirsical Conversation with Joy Dunlop

Muirsical Conversation with Joy Dunlop

Given her always busy nature and multi-disciplined lifestyle it’s a wonder bilingual Scottish singer Joy Dunlop found the time over the last three years for a couple of new studio albums.

Aside from being a well-known BBC Scotland and BBC Alba weather presenter, Joy is part of the Speak Gaelic team, co-presents a Scottish and Irish language podcast and has since become director of the annual World Gaelic Week.

Additionally, she was involved in January’s Celtic Connections, presented BBC Radio Scotland’s Young Traditional Musician of the Year and hosted a televised event celebrating fifty years of the National Centre for Gaelic Language and Culture.

She is also involved in the Covid Choral Workshops, which have successfully continued beyond lockdowns.

And you can add in Scottish stepdancer, journalist and educator.

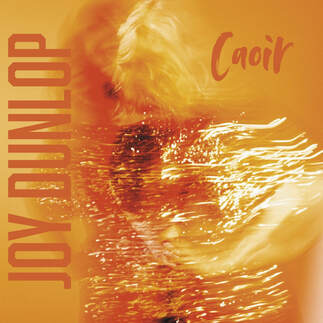

In short, a passionate advocate for all things Scottish Gaelic, including, of course, the music – which she voices beautifully on new solo album Caoir (pronounced koor), an inviting and highly accessible traditional Scots Gaelic/ folk album in the company of a full band.

And then there’s 2000 album Dithis (Duo), an ethereal blend of classical and traditional in the company of her classical pianist brother, Andrew Dunlop.

The ever-busy Joy Dunlop found time to sit down with FabricationsHQ to discuss both Dithis and Caoir, the love of working with a full band and her love and passion for the Scottish Gaelic language and its music...

Aside from being a well-known BBC Scotland and BBC Alba weather presenter, Joy is part of the Speak Gaelic team, co-presents a Scottish and Irish language podcast and has since become director of the annual World Gaelic Week.

Additionally, she was involved in January’s Celtic Connections, presented BBC Radio Scotland’s Young Traditional Musician of the Year and hosted a televised event celebrating fifty years of the National Centre for Gaelic Language and Culture.

She is also involved in the Covid Choral Workshops, which have successfully continued beyond lockdowns.

And you can add in Scottish stepdancer, journalist and educator.

In short, a passionate advocate for all things Scottish Gaelic, including, of course, the music – which she voices beautifully on new solo album Caoir (pronounced koor), an inviting and highly accessible traditional Scots Gaelic/ folk album in the company of a full band.

And then there’s 2000 album Dithis (Duo), an ethereal blend of classical and traditional in the company of her classical pianist brother, Andrew Dunlop.

The ever-busy Joy Dunlop found time to sit down with FabricationsHQ to discuss both Dithis and Caoir, the love of working with a full band and her love and passion for the Scottish Gaelic language and its music...

Ross Muir: As mentioned in the introduction, you are an incredibly busy girl with many strings to your bow.

How do you find the time to manage, and maintain balance, across all your various jobs, music artistry and Scots Gaelic endeavours?

Joy Dunlop: I think I’m very lucky in that what I get to do is all very enjoyable – and you are always going to make time for the things you enjoy! It’s all work, but at the same time it feels an awful lot like having a lot of great hobbies – and a lot of my hobbies are linked to both Gaelic and music.

Also I’m quite organised, everything in its folder [laughs], which you have to be if you are quite a busy person; I really feel that’s true. That way you can make time for the things you want to do.

But, at the same time, something’s always got to give, and that’s part of the reason it’s taken ten years to get another solo album out, because the thing that usually goes on the back burner is your own project!

I always make sure that whatever I have said to somebody else, that I’ll do, gets done first.

Then I’ll come to my own projects, usually last!

RM: And that’s how you find the balance, albeit, as you’ve just said, something has to give or get to the back of the queue…

JD: And having the understanding that you are going to have to work a lot. I mean I work all the time, but I enjoy it; I’m not complaining about that does become your life.

But neither am I saying that I don’t have a social life! [laughs]

RM: I hear that. Sometimes I feel my own social life is the music support, in all its capacities; but as you have just said you tend to make time for what you enjoy and love doing, which in my case ranges from covering or promoting everything from the traditional music scene to progressive metal.

JD: But isn’t that the wonder and love of music though?

RM: Yes, exactly that – in all its shapes and forms.

Which leads nicely to Dithis, the primarily piano and vocal album you did with your brother back in 2020.

That’s a lovely, evocative, crossover album that blends classical and your own traditional sensibilities, but it also tells the tale of what must have been a musical divergence at some stage when you were both younger?

JD: It’s kind of an interesting one because both of us actually grew up doing both – the classical, along with folk and trad.

The difference is I’m just a terrible instrumentalist who didn’t practice a lot! [laughs]

There’s four of us in the family and we’ve always had that music in our lives, but I did a language degree, which definitely helped take me down the trad. side, whereas Andrew did a classical music degree, so that obviously took him down that side.

Now, during those times, if I ever needed a pianist Andrew would always be there for me, or make himself available for Ceilidhs, that sort of thing.

So we both were in tandem early – all through school we would be doing Ceilidhs but we were also doing concerts; it’s just later he went the classical way and I went the folk and trad. way.

RM: An early dovetailing before that genre divergence, if you will.

JD: Absolutely, and that dovetailing was very common for us, in the Argyll area; there were a lot of people doing classical music and trad. because there was the opportunity to do so.

In fact, bizarrely, there were two ballet schools in the next village; just so many people in the valley listening to, or playing, classical music but then going to a Ceilidh dance!

But that’s true of any rural area, you kind of take to whatever opportunities are there.

RM: What you have just relayed makes even more sense in terms of the resonance of Dithis.

On the face of it, that album might be perceived as two very different musical worlds, but it’s a beautiful dovetailing.

There’s also a lovely rawness to some of it, as well as being quite ethereal in places, with plenty of space for piano and voice to play in.

JD: Yeah, we recorded live as much as we could, and you can really hear that; it's not that kind of clean, or close sound you might expect.

We recorded the album insitu, with the two of us performing at the same time; that’s harder in some ways but it’s how Andrew and I have always performed. We just did what we do naturally, and then would see how it came out.

We did play around with a few different bits but most of it was very natural.

How do you find the time to manage, and maintain balance, across all your various jobs, music artistry and Scots Gaelic endeavours?

Joy Dunlop: I think I’m very lucky in that what I get to do is all very enjoyable – and you are always going to make time for the things you enjoy! It’s all work, but at the same time it feels an awful lot like having a lot of great hobbies – and a lot of my hobbies are linked to both Gaelic and music.

Also I’m quite organised, everything in its folder [laughs], which you have to be if you are quite a busy person; I really feel that’s true. That way you can make time for the things you want to do.

But, at the same time, something’s always got to give, and that’s part of the reason it’s taken ten years to get another solo album out, because the thing that usually goes on the back burner is your own project!

I always make sure that whatever I have said to somebody else, that I’ll do, gets done first.

Then I’ll come to my own projects, usually last!

RM: And that’s how you find the balance, albeit, as you’ve just said, something has to give or get to the back of the queue…

JD: And having the understanding that you are going to have to work a lot. I mean I work all the time, but I enjoy it; I’m not complaining about that does become your life.

But neither am I saying that I don’t have a social life! [laughs]

RM: I hear that. Sometimes I feel my own social life is the music support, in all its capacities; but as you have just said you tend to make time for what you enjoy and love doing, which in my case ranges from covering or promoting everything from the traditional music scene to progressive metal.

JD: But isn’t that the wonder and love of music though?

RM: Yes, exactly that – in all its shapes and forms.

Which leads nicely to Dithis, the primarily piano and vocal album you did with your brother back in 2020.

That’s a lovely, evocative, crossover album that blends classical and your own traditional sensibilities, but it also tells the tale of what must have been a musical divergence at some stage when you were both younger?

JD: It’s kind of an interesting one because both of us actually grew up doing both – the classical, along with folk and trad.

The difference is I’m just a terrible instrumentalist who didn’t practice a lot! [laughs]

There’s four of us in the family and we’ve always had that music in our lives, but I did a language degree, which definitely helped take me down the trad. side, whereas Andrew did a classical music degree, so that obviously took him down that side.

Now, during those times, if I ever needed a pianist Andrew would always be there for me, or make himself available for Ceilidhs, that sort of thing.

So we both were in tandem early – all through school we would be doing Ceilidhs but we were also doing concerts; it’s just later he went the classical way and I went the folk and trad. way.

RM: An early dovetailing before that genre divergence, if you will.

JD: Absolutely, and that dovetailing was very common for us, in the Argyll area; there were a lot of people doing classical music and trad. because there was the opportunity to do so.

In fact, bizarrely, there were two ballet schools in the next village; just so many people in the valley listening to, or playing, classical music but then going to a Ceilidh dance!

But that’s true of any rural area, you kind of take to whatever opportunities are there.

RM: What you have just relayed makes even more sense in terms of the resonance of Dithis.

On the face of it, that album might be perceived as two very different musical worlds, but it’s a beautiful dovetailing.

There’s also a lovely rawness to some of it, as well as being quite ethereal in places, with plenty of space for piano and voice to play in.

JD: Yeah, we recorded live as much as we could, and you can really hear that; it's not that kind of clean, or close sound you might expect.

We recorded the album insitu, with the two of us performing at the same time; that’s harder in some ways but it’s how Andrew and I have always performed. We just did what we do naturally, and then would see how it came out.

We did play around with a few different bits but most of it was very natural.

RM: Much like Dithis, there's a very natural sound, and feel, to your new solo album Caoir, which features a full band including fiddle, guitar, bass and drums.

That instrumentation works very well but given what we’ve just discussed as regards Dithis and piano, it’s interesting you chose not to add piano or indeed any keys instrumentation, such as accordion, which is perhaps deemed more traditional.

JD: Well accordion is not an instrument I work with very often and while I’ve worked a lot with piano and my brother Andrew, I wanted a band that could go out and perform as just that – a band; I also wanted drums, bass and guitar.

I would have piano, but then, if I could, I’d have a band of about twelve, but that’s just not do-able!

Also, I’ve worked with Ron Jappy before, on guitar, and wanted to work with him more; I’ve also worked with fiddle player Mhairi Marwick, plus I love drums and I love bass, so it made sense to have that line-up.

That’s five of us, which is do-able; it’s pushing it a little but it’s still viable. Piano could be added but I really wanted it to be a band album.

RM: Which really comes across on both the opener, Jigs, and album closer The Reels; the latter in particular has that great folk 'n' roll feel, but you can still arrange for the more traditional Scots Gaelic.

It’s the best of both worlds.

JD: I don’t see it as two different worlds though, and I think that, for me, is the issue with Gaelic.

People go "oh, that has to go over there because it can’t be part of this, and it isn’t part of that."

But why not? Why is it any different to anything else that people have been doing with drums and bass? That’s how I see it.

I don’t ever think "oh my goodness I really want to get into these different genres, and will, if I’m lucky with my Gaelic." It’s more a case of wanting to do something with Gaelic that musically, for me, works.

I don’t see Gaelic as a negative; I don’t see it as a harder sell; I don’t see it as being something that needs changed to have it fit different things. From my side of things, I just want make good music.

RM: Absolutely, and my both worlds comment wasn’t an indicator of niching or bracketing, more that with a band such as this you can take the folk and trad. anywhere you like and, as you have just said, and proven with Caoir, make good music.

Another aspect of Caoir, and indeed very much part of Scots Gaelic music, is the fast-paced rhythm of puirt à beul, or mouth music – there is such a beautiful lyrical cadence to Scots Gaelic in both spoken word and song that the two seem inexorably linked.

JD: Well Gaelic songs were all composed for a reason, for a purpose, and puirt à beul was and is music for dancing, so the words were chosen for the lift that they give and the rhythms they create.

So you approach them with dancing in mind – I dance as well, and I believe that helps because you understand the beat and you understand the feel.

But, like anything else, it’s practice. If you were a fiddle player just learning the first thing you’d be expected to play wouldn’t be a reel; you’d start much slower and work up.

It's exactly the same with puirt à beul, which is all about having control of your breathing; learning where to breath so you can support the singing, and knowing the song really well so you can get it really tight.

But you can also do puirt à beul really badly [laughs]; I don’t think there is any singer out there who hasn’t gone "ah, I’ve just made a grave error here!"

That could be singing too fast, or being in the wrong key, or doing something else wrong, but that’s why you practice, and why you work on it.

It is fun though. I love singing puirt à beul; the melody is in the singing, you really are driving it.

RM: And it’s inherently infectious. You can’t not start a shoulder shake, or a foot tapping, or a hand clapping.

JD: Which you probably have in any type of fast, dancing music – you wouldn’t expect to listen to salsa and be sitting there with your arms crossed; you’d be thinking "this is music for dancing – I want to move!"

Puirt à beul is the same, it is inherent, because it was created for dancing; if you’re not getting that lift, or that beat, or the feel, then you are not doing it properly! That’s the very ethos of it; it’s about capturing that spirit.

That instrumentation works very well but given what we’ve just discussed as regards Dithis and piano, it’s interesting you chose not to add piano or indeed any keys instrumentation, such as accordion, which is perhaps deemed more traditional.

JD: Well accordion is not an instrument I work with very often and while I’ve worked a lot with piano and my brother Andrew, I wanted a band that could go out and perform as just that – a band; I also wanted drums, bass and guitar.

I would have piano, but then, if I could, I’d have a band of about twelve, but that’s just not do-able!

Also, I’ve worked with Ron Jappy before, on guitar, and wanted to work with him more; I’ve also worked with fiddle player Mhairi Marwick, plus I love drums and I love bass, so it made sense to have that line-up.

That’s five of us, which is do-able; it’s pushing it a little but it’s still viable. Piano could be added but I really wanted it to be a band album.

RM: Which really comes across on both the opener, Jigs, and album closer The Reels; the latter in particular has that great folk 'n' roll feel, but you can still arrange for the more traditional Scots Gaelic.

It’s the best of both worlds.

JD: I don’t see it as two different worlds though, and I think that, for me, is the issue with Gaelic.

People go "oh, that has to go over there because it can’t be part of this, and it isn’t part of that."

But why not? Why is it any different to anything else that people have been doing with drums and bass? That’s how I see it.

I don’t ever think "oh my goodness I really want to get into these different genres, and will, if I’m lucky with my Gaelic." It’s more a case of wanting to do something with Gaelic that musically, for me, works.

I don’t see Gaelic as a negative; I don’t see it as a harder sell; I don’t see it as being something that needs changed to have it fit different things. From my side of things, I just want make good music.

RM: Absolutely, and my both worlds comment wasn’t an indicator of niching or bracketing, more that with a band such as this you can take the folk and trad. anywhere you like and, as you have just said, and proven with Caoir, make good music.

Another aspect of Caoir, and indeed very much part of Scots Gaelic music, is the fast-paced rhythm of puirt à beul, or mouth music – there is such a beautiful lyrical cadence to Scots Gaelic in both spoken word and song that the two seem inexorably linked.

JD: Well Gaelic songs were all composed for a reason, for a purpose, and puirt à beul was and is music for dancing, so the words were chosen for the lift that they give and the rhythms they create.

So you approach them with dancing in mind – I dance as well, and I believe that helps because you understand the beat and you understand the feel.

But, like anything else, it’s practice. If you were a fiddle player just learning the first thing you’d be expected to play wouldn’t be a reel; you’d start much slower and work up.

It's exactly the same with puirt à beul, which is all about having control of your breathing; learning where to breath so you can support the singing, and knowing the song really well so you can get it really tight.

But you can also do puirt à beul really badly [laughs]; I don’t think there is any singer out there who hasn’t gone "ah, I’ve just made a grave error here!"

That could be singing too fast, or being in the wrong key, or doing something else wrong, but that’s why you practice, and why you work on it.

It is fun though. I love singing puirt à beul; the melody is in the singing, you really are driving it.

RM: And it’s inherently infectious. You can’t not start a shoulder shake, or a foot tapping, or a hand clapping.

JD: Which you probably have in any type of fast, dancing music – you wouldn’t expect to listen to salsa and be sitting there with your arms crossed; you’d be thinking "this is music for dancing – I want to move!"

Puirt à beul is the same, it is inherent, because it was created for dancing; if you’re not getting that lift, or that beat, or the feel, then you are not doing it properly! That’s the very ethos of it; it’s about capturing that spirit.

RM: From toe-tapping reels and puirt à beul to the plaintive and poignant side of Caoir, through the tales of unrequited love, loss and longing; all inherent story telling traits of Scots Gaelic music.

One such example is the lament Cadal Cuain, or Sleep of the Ocean.

Melancholic it may be but there is a beauty and grace to the song via its considered arrangement and Marih’s emotive fiddle.

JD: Thank you. We purposely looked hard at the arrangements, particularly with the laments, which are sad because of the stories within them.

When the band were working out their instrumentation, I was going through that with them, saying "you can’t be too loud at this bit" or "you can’t swell the sound here" – and that's because I understand the words but nobody else does! [laughs]. So you have to break it all down.

And that’s the hope with songs like that on the album, that Gaels will get it – because it will make sense to them – and non-speakers of the language.

I‘m not trying to play to the English speaking market – I don’t want a Gaelic speaker to listen to it and say "oh you’ve ripped the soul out of this song" – you still want people to understand it and think yes, the sentiment is there, the heart is there. We worked very hard on that and there were things we tried that just did not work.

I remember one song where the musicians all played it beautifully, really going for it, and I was just sitting there, listening. When they finished they said "what do you think?"

And I said "It doesn’t work, for me, with the lyric."

They had changed around the melody and it sounded great musically – they were all saying "we really love that!" But I didn’t, unfortunately [laughs]

I had to say "as a piece of music, that is beautiful; but I can’t sing along with it."

But that’s the wonder of working with people who are not only great musicians but good friends and very professional – you can go "that was wonderful, but it’s not quite right for this song, with its lyric."

So we tried to really take care with that; respecting the sentiment of the songs and trying to interpret the meaning of the words and carry that feeling through the music, rather than "OK I’ll do this and everyone else just plays along."

We really did work hard on that, getting the drums and the bass right, the swell of the music, the fiddle; how we put it all together.

And, actually, that particular song Cadal Cuain?

The poet Ceitidh Morrison, who wrote the words of the song, contacted me to say she had heard our version and really liked it, because she thought we had stayed true to the essences of the song and that our arrangement worked really well.

I thought that was lovely; I was really touched by that, because that’s always your worry, that someone will listen and say "well, I don’t like your version of that song!" [laughs].

RM: Ceitidh’s comments are also a testament to the work you and the band put in though, as you have just described; retaining the musical heart and lyrical soul of the songs on Caoir...

One such example is the lament Cadal Cuain, or Sleep of the Ocean.

Melancholic it may be but there is a beauty and grace to the song via its considered arrangement and Marih’s emotive fiddle.

JD: Thank you. We purposely looked hard at the arrangements, particularly with the laments, which are sad because of the stories within them.

When the band were working out their instrumentation, I was going through that with them, saying "you can’t be too loud at this bit" or "you can’t swell the sound here" – and that's because I understand the words but nobody else does! [laughs]. So you have to break it all down.

And that’s the hope with songs like that on the album, that Gaels will get it – because it will make sense to them – and non-speakers of the language.

I‘m not trying to play to the English speaking market – I don’t want a Gaelic speaker to listen to it and say "oh you’ve ripped the soul out of this song" – you still want people to understand it and think yes, the sentiment is there, the heart is there. We worked very hard on that and there were things we tried that just did not work.

I remember one song where the musicians all played it beautifully, really going for it, and I was just sitting there, listening. When they finished they said "what do you think?"

And I said "It doesn’t work, for me, with the lyric."

They had changed around the melody and it sounded great musically – they were all saying "we really love that!" But I didn’t, unfortunately [laughs]

I had to say "as a piece of music, that is beautiful; but I can’t sing along with it."

But that’s the wonder of working with people who are not only great musicians but good friends and very professional – you can go "that was wonderful, but it’s not quite right for this song, with its lyric."

So we tried to really take care with that; respecting the sentiment of the songs and trying to interpret the meaning of the words and carry that feeling through the music, rather than "OK I’ll do this and everyone else just plays along."

We really did work hard on that, getting the drums and the bass right, the swell of the music, the fiddle; how we put it all together.

And, actually, that particular song Cadal Cuain?

The poet Ceitidh Morrison, who wrote the words of the song, contacted me to say she had heard our version and really liked it, because she thought we had stayed true to the essences of the song and that our arrangement worked really well.

I thought that was lovely; I was really touched by that, because that’s always your worry, that someone will listen and say "well, I don’t like your version of that song!" [laughs].

RM: Ceitidh’s comments are also a testament to the work you and the band put in though, as you have just described; retaining the musical heart and lyrical soul of the songs on Caoir...

RM: From the Scots Gaelic songs to the language itself.

If anyone is curious about Scots Gaelic, or has a keen willingness to learn the language, where and what are the Joy Dunlop recommendations?

JD: Oh there are so many resources now, many of which are free and on-line.

If you were just wanting to start out, with a free introduction, get on the duolingo app, it’s a great Scottish Gaelic course.

If you are looking for something that gives you that bit more, learning wise, then we have the Speak Gaelic course, which is totally free. I present that one on BBC Alba but I don’t have any affiliation – it doesn’t make me any money so I can plug it as much as I like! [laughter].

But I do honestly think it’s a really good course and, as mentioned, it’s free, with all the resources like Podcasts on-line; there’s just so much to do with the Speak Gaelic courses out there.

But I would say, like anything else, you can’t expect one course to give you everything, unless you are doing a full-time course like the Distance Learning course from Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, the National Centre for Galic Language and Culture.

if you’re willing to put a bit of money and time behind it then I think it’s the best one out there, as regards a standardised, follow-a-course of learning.

Others you can dip in and out of in your own time but with that one you’re signing up and committing to do classes and course work in your own time.

RM: Another musical strength that we can’t not touch on is the Covid Choral Workshop, which has proven so successful that it continues on now, well past the lockdowns.

There were very few positives to come out of Covid but one was definitely that feeling of community spirit in front of screens to share a mutual love of something, in this case singing…

JD: Absolutely! Anybody that sings in a choir knows that the worst thing about the lockdowns was that we couldn’t sing together – and Zoom doesn’t let you sing with other people in real time.

So, basically, we just started getting together to note bash a lot of songs, or sing along with some recordings. But now, it’s really taken off!

Back at Christmas time I had said to them "do you want to keep going?" because we were practicing with our own choirs by then and people are busy with other things.

But everybody replied with a resounding yes, saying they still wanted to do this, even if I couldn't make every one.

And what’s really nice is we’ve got a wee community now; ninety-five percent of us sing in different Gaelic choirs so, on varying levels, we kind of know each other – which means it’s great if we go to the Mod and see someone from the lockdown choir – "ah it’s you!" [laughs]

In fact the Covid Choral Choir, all of us together, for the first time, performed at the Mod.

RM: Really? That’s wonderful.

JD: Yeah, when the Mod came back the first time after lockdown it wasn’t really a competition; they opened it up for performances and we sang as the Covid Choral Choir – that was the first time most of us had met, it was really lovely.

As I said earlier we have now created this nice wee community that meets up every two weeks just to sing together, and learn. I teach them choral songs, we sit back and we chat.

But the one good thing about originally doing the choral stuff on-line is geography – as in it isn’t a barrier.

For example, I have three that come from Australia and one of them, Ron – and this shows how small the world has become – is based in Melbourne, where my brother Andrew was working recently.

Andrew met up with Ron who had been coming to my Covid Choral Workshop!

So people like Ron already know me through Andrew; in fact he was already coming to the on-line Ceilidh’s that I’ve been running and my mum organises; it’s almost like he’s become a close friend, despite the fact we have not met in person, but he’s met my brother over in Melbourne.

The world is small, but now it feels even smaller!

That side of the on-line workshops has been lovely. Some people talk about how much they hate Zoom but I quite like Zoom; but then I wasn’t using it every day, nine to five, for work; I was using it to connect with people. That’s why I enjoyed it; that was my interaction with other people.

RM: The other positive is, of course, that music is such a great unifier – and now, with the likes of Zoom, you can be on the other side of the world yet just a few feet apart in front of a screen, sharing a passion for music.

JD: Totally. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not a replacement for being there together – in fact I cried for about six months at any music event I went to, which is very unlike me because girls from Argyll don’t do that! [laughs].

But all of a sudden I was going to concerts or Ceilidhs and just bawling, because it was like a physical, visceral hit – this is what we had been missing; singing in person again and hearing voices around me, making music; that is something really special.

But, if you don’t have that, or you wanted to learn from somebody, you can do that over Zoom; you can do a one-to-one thing quite easily. It’s not for everyone, but it has really opened up a lot of opportunities.

RM: Your comments there about community, and making friends through music, is such a truism and such an important bond for so many. Music and close friendships; couldn’t do without either, frankly.

If anyone is curious about Scots Gaelic, or has a keen willingness to learn the language, where and what are the Joy Dunlop recommendations?

JD: Oh there are so many resources now, many of which are free and on-line.

If you were just wanting to start out, with a free introduction, get on the duolingo app, it’s a great Scottish Gaelic course.

If you are looking for something that gives you that bit more, learning wise, then we have the Speak Gaelic course, which is totally free. I present that one on BBC Alba but I don’t have any affiliation – it doesn’t make me any money so I can plug it as much as I like! [laughter].

But I do honestly think it’s a really good course and, as mentioned, it’s free, with all the resources like Podcasts on-line; there’s just so much to do with the Speak Gaelic courses out there.

But I would say, like anything else, you can’t expect one course to give you everything, unless you are doing a full-time course like the Distance Learning course from Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, the National Centre for Galic Language and Culture.

if you’re willing to put a bit of money and time behind it then I think it’s the best one out there, as regards a standardised, follow-a-course of learning.

Others you can dip in and out of in your own time but with that one you’re signing up and committing to do classes and course work in your own time.

RM: Another musical strength that we can’t not touch on is the Covid Choral Workshop, which has proven so successful that it continues on now, well past the lockdowns.

There were very few positives to come out of Covid but one was definitely that feeling of community spirit in front of screens to share a mutual love of something, in this case singing…

JD: Absolutely! Anybody that sings in a choir knows that the worst thing about the lockdowns was that we couldn’t sing together – and Zoom doesn’t let you sing with other people in real time.

So, basically, we just started getting together to note bash a lot of songs, or sing along with some recordings. But now, it’s really taken off!

Back at Christmas time I had said to them "do you want to keep going?" because we were practicing with our own choirs by then and people are busy with other things.

But everybody replied with a resounding yes, saying they still wanted to do this, even if I couldn't make every one.

And what’s really nice is we’ve got a wee community now; ninety-five percent of us sing in different Gaelic choirs so, on varying levels, we kind of know each other – which means it’s great if we go to the Mod and see someone from the lockdown choir – "ah it’s you!" [laughs]

In fact the Covid Choral Choir, all of us together, for the first time, performed at the Mod.

RM: Really? That’s wonderful.

JD: Yeah, when the Mod came back the first time after lockdown it wasn’t really a competition; they opened it up for performances and we sang as the Covid Choral Choir – that was the first time most of us had met, it was really lovely.

As I said earlier we have now created this nice wee community that meets up every two weeks just to sing together, and learn. I teach them choral songs, we sit back and we chat.

But the one good thing about originally doing the choral stuff on-line is geography – as in it isn’t a barrier.

For example, I have three that come from Australia and one of them, Ron – and this shows how small the world has become – is based in Melbourne, where my brother Andrew was working recently.

Andrew met up with Ron who had been coming to my Covid Choral Workshop!

So people like Ron already know me through Andrew; in fact he was already coming to the on-line Ceilidh’s that I’ve been running and my mum organises; it’s almost like he’s become a close friend, despite the fact we have not met in person, but he’s met my brother over in Melbourne.

The world is small, but now it feels even smaller!

That side of the on-line workshops has been lovely. Some people talk about how much they hate Zoom but I quite like Zoom; but then I wasn’t using it every day, nine to five, for work; I was using it to connect with people. That’s why I enjoyed it; that was my interaction with other people.

RM: The other positive is, of course, that music is such a great unifier – and now, with the likes of Zoom, you can be on the other side of the world yet just a few feet apart in front of a screen, sharing a passion for music.

JD: Totally. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not a replacement for being there together – in fact I cried for about six months at any music event I went to, which is very unlike me because girls from Argyll don’t do that! [laughs].

But all of a sudden I was going to concerts or Ceilidhs and just bawling, because it was like a physical, visceral hit – this is what we had been missing; singing in person again and hearing voices around me, making music; that is something really special.

But, if you don’t have that, or you wanted to learn from somebody, you can do that over Zoom; you can do a one-to-one thing quite easily. It’s not for everyone, but it has really opened up a lot of opportunities.

RM: Your comments there about community, and making friends through music, is such a truism and such an important bond for so many. Music and close friendships; couldn’t do without either, frankly.

JD: We have a saying in Gaelic, Thig crìoch air an t-saoghal, ach mairidh gaol is ceòl.

Translated that means the world could end, but love and music will endure.

Over the last few years, with the pandemic and lockdowns, I don’t know how many times I’ve either said that or written it on things; there’s never been a saying that has rang so true.

And we are so lucky to have what we’ve got; this culture and this heritage.

In fact I’m not long back from New York’s Tartan Week.

I was over there in April and they celebrate everything to do with Scotland. For such a tiny country it’s wonderful how the Scots have impacted in not Just New York but so many other places. We’re so lucky!

RM: Indeed. We’re small, but perfectly formed.

JD: [laughs] Yes, I like to tell everybody that! It’s funny because they are all uber-Scottish over there – one American said to me, and he said it so seriously, "you know Joy, if it’s not Scottish it’s crap!" [laughs].

RM: Love it [laughs]. I recall that line originating in a sketch by Canadian comedian and actor Mike Myers, who has Scottish heritage; it’s great to hear it has taken on a life of its own.

JD: Well, he’s not wrong! As the man was telling me that I was saying "but you’re American."

He said "no, we’re Scottish, and we know." [laughs].

And that was great because abroad, they seem to understand it a bit more, whereas here at home we can be a bit apathetic about it.

RM: Well, with people like you quite literally singing our praises and championing Gaelic culture we can hopefully turn any apathy back into appreciation for what we have.

Thanks for spending time with FabricationsHQ Joy, it’s been a pleasure.

JD: Thank you so much for all your support, Ross; it’s very much appreciated!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Joy Dunlop.

Purchase Caoir and other Joy Dunlop albums and merch at: https://www.joydunlop.com/shop/

Read FabricationsHQ's feature review of Caoir here

Photo Credits: official media images from Joy Dunlop website

Translated that means the world could end, but love and music will endure.

Over the last few years, with the pandemic and lockdowns, I don’t know how many times I’ve either said that or written it on things; there’s never been a saying that has rang so true.

And we are so lucky to have what we’ve got; this culture and this heritage.

In fact I’m not long back from New York’s Tartan Week.

I was over there in April and they celebrate everything to do with Scotland. For such a tiny country it’s wonderful how the Scots have impacted in not Just New York but so many other places. We’re so lucky!

RM: Indeed. We’re small, but perfectly formed.

JD: [laughs] Yes, I like to tell everybody that! It’s funny because they are all uber-Scottish over there – one American said to me, and he said it so seriously, "you know Joy, if it’s not Scottish it’s crap!" [laughs].

RM: Love it [laughs]. I recall that line originating in a sketch by Canadian comedian and actor Mike Myers, who has Scottish heritage; it’s great to hear it has taken on a life of its own.

JD: Well, he’s not wrong! As the man was telling me that I was saying "but you’re American."

He said "no, we’re Scottish, and we know." [laughs].

And that was great because abroad, they seem to understand it a bit more, whereas here at home we can be a bit apathetic about it.

RM: Well, with people like you quite literally singing our praises and championing Gaelic culture we can hopefully turn any apathy back into appreciation for what we have.

Thanks for spending time with FabricationsHQ Joy, it’s been a pleasure.

JD: Thank you so much for all your support, Ross; it’s very much appreciated!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Joy Dunlop.

Purchase Caoir and other Joy Dunlop albums and merch at: https://www.joydunlop.com/shop/

Read FabricationsHQ's feature review of Caoir here

Photo Credits: official media images from Joy Dunlop website