Just Peachy

Muirsical Conversation with Mike Ross

Muirsical Conversation with Mike Ross

British musician Mike Ross, who has a knack for mixing blues-rock, Americana and rootsier blues (and the occasional splash of electronica) in fine musical style (as showcased on his recent brace of Clovis Limit albums) has been in a musically nostalgic frame of mind of late.

Following the aforementioned Clovis Limit albums (and dovetailing Tennessee Transition release) Mike Ross cleaned up, restored, fully mixed and issued the never completed 1998 album Lay it Bare by Taller Than (a 60s/70s blues-rock styled power-trio featuring Ross, his brother Graeme on bass and drummer Mick Kelly).

He then found time to re-record a batch of songs from earlier in his career, subsequently releasing them as the fittingly titled Origin Story.

And, now, in what is a true labour of love, comes Peach Jam by the Mike Ross Band.

An intentionally retro-styled release (from cover art to songs within) Peach Jam takes its inspiration from the musical stylings of the Allman Brothers Band, specifically the 1971 Fillmore iteration.

Following the aforementioned Clovis Limit albums (and dovetailing Tennessee Transition release) Mike Ross cleaned up, restored, fully mixed and issued the never completed 1998 album Lay it Bare by Taller Than (a 60s/70s blues-rock styled power-trio featuring Ross, his brother Graeme on bass and drummer Mick Kelly).

He then found time to re-record a batch of songs from earlier in his career, subsequently releasing them as the fittingly titled Origin Story.

And, now, in what is a true labour of love, comes Peach Jam by the Mike Ross Band.

An intentionally retro-styled release (from cover art to songs within) Peach Jam takes its inspiration from the musical stylings of the Allman Brothers Band, specifically the 1971 Fillmore iteration.

Peach Jam is also his eighth studio release in less than four years, making Mike Ross one of the most prolific artists in the period just prior to, during, and following, the Covid-19 pandemic and related lockdowns.

Mike Ross is also as affable, genuine and chatty a muso as you’ll meet, going in to enthused detail about the creation, recording and influences behind Peach Jam as well as 2019’s almost fully improvised instrumental album Hotel Toledo, the second release from guitar trio RHR (Troy Redfern, Jack J Hutchinson, Mike Ross).

But the conversation opened with the 'cover story' behind Peach Jam...

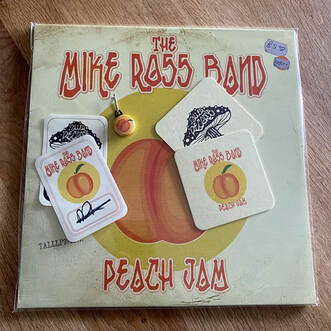

Ross Muir: The cover sleeve for the vinyl edition of Peach Jam is as interesting and 70s inspired as the songs within; a clever and fun nod to 70s album art, from the colour tones and trippy font type to the staining and the £5.00 price sticker. The latter is a particularly nice touch, albeit a fiver is underselling yourself a tad...

Mike Ross: Yeah, but it’s a second hand record! [laughs]

RM: [laughs] Indeed; straight from the cut-out/ second hand record bin, with the VG/ Excellent-plus sticker, which is another nice touch. But my point is Peach Jam, from outer cover art to song-craft within, is clearly a labour of early 70s Allmans inspired love…

MR: Definitely; it’s certainly not financial [laughs] – my goal with all of these lockdown projects was to get enough money to pay myself back.

I’m still a big music fan, and when I was a teenager we used to go to Newcastle on the train and I’d have my thirty-five quid a week from the Youth Training Scheme, and we’d go to second hand record shops and I’d buy things like 461 Ocean Boulevard, Axis Bold as Love, or Hendrix in the West, those sort of albums.

There were also bootlegs available by a company called The Swingin’ Pig, and they were always done on coloured vinyl and usually the best quality ones you could get.

Anyway, what I really remember was the grading system for the second-hand records, which was done with two grades, one for the sleeve and one for the record.

Some records shops would have a sticker that said MM, for mint, but that would be a lie because it would be knackered! [laughs]

But, as you see on Peach Jam, the sleeve is clearly tea stained and a bit wrinkled, so it’s VG for very good.

Then there's the slash and EX+ for excellent plus, which is one off mint because no record is ever mint, as soon as you take them out their sleeves, even just to look the, they get dust on them, or scratched.

So those stickers are my stamp of authenticity!

RM: Authenticity is the perfect word to describe this album because it really is a homage to that yesteryear of vinyl records and, as you stated in pre-release press, a homage to, and inspired by, the Allman Brothers band in their 71 Fillmore iteration.

But there’s a lot of a other colours running through the album too – for example the 15 minute title track, a musical journey from Atlanta, Georgia to Sarasota in Florida, takes a number of Mike Ross twists and turns on that musical road. There’s a lot going on here beyond an Allman Brothers nod.

MR: Well, to give you the process composing Peach Jam, I wrote the head section by just sitting with the guitar and playing some chords [picks up guitar and plays the head/ intro]; I like to mess about with those particular chords because they are just pleasing.

So I found that little sequence, in 5/4 time, then recorded it into my phone – I record everything into a little recorder app on my phone initially, then come down to my studio to see what I can do with it.

So the head came first, then the melody, then an idea about adding harmony guitar, and off we go!

But I didn’t want a whole song in 5/4, so I thought let’s find something a bit more straight-forward; I wanted to do something that reminded me of A Kind Of Blue by Miles Davis – the Allman Brothers used to get really stoned and listen to A Kind Of Blue in the Big House in Macon, then go to the studio next door and jam, which is where In Memory of Elizabeth Reed comes from and those changes that go up down a semi-tone – you just don’t hear those in rock, ever.

So I borrowed that idea for a section, then the head comes back in, followed by a little shuffle section.

There are also comparisons with the Allman Brothers track Mountain Jam, because they come back in after the drum solo to go into a shuffle; so I thought right, I’ll have a shuffle!

Now the only thing missing was a bit of In Memory of Elizabeth Reed, which is the jazzy bit.

RM: And these musical changes are paralleling the scenic changes on the journey from Atlanta to Sarasota.

MR: Yes. I had just been reading an interview with Dicky Betts where he was talking about living in Sarasota. I’ve spent a bit of time down there and have done the journey from Atlanta to Sarasota – Peach Jam is not a replication of that journey but I know a bit about the area.

When I was putting the track together I thought this could be a bit of a journey, because that 5/4 section is quite urban; then the fast bit is you getting out of the city and on to the motorway; the shuffle is you having a good time on the drive as the music is kicking in.

Then you get to Florida, with its coast on the panhandle, which is quite Caribbean really – that’s the bass groove in the jazzy, funky section; it’s very Caribbean.

There’s a track called Funky Nassau, which I’ve always loved, by The Beginning of the End; it’s not a copy of that by any stretch but it’s reminiscent of that; it’s got that kind of relaxed vibe.

RM: So there is semi-improvisation here; a sketch on where the song was headed on its journey.

MR: Well It kind of wrote itself; I certainly didn’t have this conscious idea of doing it this way.

Also the very beginning, where you can hear a bit of traffic noise? That’s a highway in Atlanta.

When I was last in Atlanta, which was 2018 to record Clovis One, in Nashville, I stayed with a friend who lives in downtown Atlanta. We were walking back after having breakfast and we were on the pedestrian bridge over the big highway that goes all the way around Atlanta, and I filmed it, because I wanted a memory of it.

That turned out to be the beginning of the Peach Jam journey!

RM: You also add a clever soundbite at the end, too.

MR: Yeah; I also like psychedelic music so I added that backwards effect – I have the tools here in the studio to do that so I just thought, why not!

RM: I’d also like to give a nod here to what is a great Rhodes solo on Peach Jam..

MR: That’s my mate Matt Slocum; he currently plays with a band called Railroad Earth, who are a huge Bluegrass/ psychedelic jam band at the top of their game.

He’s also played with the late Colonel Bruce Hampton, Jimmy Herring, who was with the Allman Brothers, Susan Tedeschi, John McLaughlin and loads of other people.

I actually met him when he was playing with Rich Robinson out of the Black Crowes; he was touring with Rich and I was working with Rich doing the guitar tech thing.

RM: That’s quite the résumé.

MR: He’s just an unbelievable organ and piano player, and a lovely guy – my brother from another mother!

RM: While Peach Jam has parts that wrote themselves as the journey unfolds, the other long-form piece, the eleven-minute Galadrielle, was mostly an improvised jam?

MR: Other than the melody, it was totally improvised...

Mike Ross is also as affable, genuine and chatty a muso as you’ll meet, going in to enthused detail about the creation, recording and influences behind Peach Jam as well as 2019’s almost fully improvised instrumental album Hotel Toledo, the second release from guitar trio RHR (Troy Redfern, Jack J Hutchinson, Mike Ross).

But the conversation opened with the 'cover story' behind Peach Jam...

Ross Muir: The cover sleeve for the vinyl edition of Peach Jam is as interesting and 70s inspired as the songs within; a clever and fun nod to 70s album art, from the colour tones and trippy font type to the staining and the £5.00 price sticker. The latter is a particularly nice touch, albeit a fiver is underselling yourself a tad...

Mike Ross: Yeah, but it’s a second hand record! [laughs]

RM: [laughs] Indeed; straight from the cut-out/ second hand record bin, with the VG/ Excellent-plus sticker, which is another nice touch. But my point is Peach Jam, from outer cover art to song-craft within, is clearly a labour of early 70s Allmans inspired love…

MR: Definitely; it’s certainly not financial [laughs] – my goal with all of these lockdown projects was to get enough money to pay myself back.

I’m still a big music fan, and when I was a teenager we used to go to Newcastle on the train and I’d have my thirty-five quid a week from the Youth Training Scheme, and we’d go to second hand record shops and I’d buy things like 461 Ocean Boulevard, Axis Bold as Love, or Hendrix in the West, those sort of albums.

There were also bootlegs available by a company called The Swingin’ Pig, and they were always done on coloured vinyl and usually the best quality ones you could get.

Anyway, what I really remember was the grading system for the second-hand records, which was done with two grades, one for the sleeve and one for the record.

Some records shops would have a sticker that said MM, for mint, but that would be a lie because it would be knackered! [laughs]

But, as you see on Peach Jam, the sleeve is clearly tea stained and a bit wrinkled, so it’s VG for very good.

Then there's the slash and EX+ for excellent plus, which is one off mint because no record is ever mint, as soon as you take them out their sleeves, even just to look the, they get dust on them, or scratched.

So those stickers are my stamp of authenticity!

RM: Authenticity is the perfect word to describe this album because it really is a homage to that yesteryear of vinyl records and, as you stated in pre-release press, a homage to, and inspired by, the Allman Brothers band in their 71 Fillmore iteration.

But there’s a lot of a other colours running through the album too – for example the 15 minute title track, a musical journey from Atlanta, Georgia to Sarasota in Florida, takes a number of Mike Ross twists and turns on that musical road. There’s a lot going on here beyond an Allman Brothers nod.

MR: Well, to give you the process composing Peach Jam, I wrote the head section by just sitting with the guitar and playing some chords [picks up guitar and plays the head/ intro]; I like to mess about with those particular chords because they are just pleasing.

So I found that little sequence, in 5/4 time, then recorded it into my phone – I record everything into a little recorder app on my phone initially, then come down to my studio to see what I can do with it.

So the head came first, then the melody, then an idea about adding harmony guitar, and off we go!

But I didn’t want a whole song in 5/4, so I thought let’s find something a bit more straight-forward; I wanted to do something that reminded me of A Kind Of Blue by Miles Davis – the Allman Brothers used to get really stoned and listen to A Kind Of Blue in the Big House in Macon, then go to the studio next door and jam, which is where In Memory of Elizabeth Reed comes from and those changes that go up down a semi-tone – you just don’t hear those in rock, ever.

So I borrowed that idea for a section, then the head comes back in, followed by a little shuffle section.

There are also comparisons with the Allman Brothers track Mountain Jam, because they come back in after the drum solo to go into a shuffle; so I thought right, I’ll have a shuffle!

Now the only thing missing was a bit of In Memory of Elizabeth Reed, which is the jazzy bit.

RM: And these musical changes are paralleling the scenic changes on the journey from Atlanta to Sarasota.

MR: Yes. I had just been reading an interview with Dicky Betts where he was talking about living in Sarasota. I’ve spent a bit of time down there and have done the journey from Atlanta to Sarasota – Peach Jam is not a replication of that journey but I know a bit about the area.

When I was putting the track together I thought this could be a bit of a journey, because that 5/4 section is quite urban; then the fast bit is you getting out of the city and on to the motorway; the shuffle is you having a good time on the drive as the music is kicking in.

Then you get to Florida, with its coast on the panhandle, which is quite Caribbean really – that’s the bass groove in the jazzy, funky section; it’s very Caribbean.

There’s a track called Funky Nassau, which I’ve always loved, by The Beginning of the End; it’s not a copy of that by any stretch but it’s reminiscent of that; it’s got that kind of relaxed vibe.

RM: So there is semi-improvisation here; a sketch on where the song was headed on its journey.

MR: Well It kind of wrote itself; I certainly didn’t have this conscious idea of doing it this way.

Also the very beginning, where you can hear a bit of traffic noise? That’s a highway in Atlanta.

When I was last in Atlanta, which was 2018 to record Clovis One, in Nashville, I stayed with a friend who lives in downtown Atlanta. We were walking back after having breakfast and we were on the pedestrian bridge over the big highway that goes all the way around Atlanta, and I filmed it, because I wanted a memory of it.

That turned out to be the beginning of the Peach Jam journey!

RM: You also add a clever soundbite at the end, too.

MR: Yeah; I also like psychedelic music so I added that backwards effect – I have the tools here in the studio to do that so I just thought, why not!

RM: I’d also like to give a nod here to what is a great Rhodes solo on Peach Jam..

MR: That’s my mate Matt Slocum; he currently plays with a band called Railroad Earth, who are a huge Bluegrass/ psychedelic jam band at the top of their game.

He’s also played with the late Colonel Bruce Hampton, Jimmy Herring, who was with the Allman Brothers, Susan Tedeschi, John McLaughlin and loads of other people.

I actually met him when he was playing with Rich Robinson out of the Black Crowes; he was touring with Rich and I was working with Rich doing the guitar tech thing.

RM: That’s quite the résumé.

MR: He’s just an unbelievable organ and piano player, and a lovely guy – my brother from another mother!

RM: While Peach Jam has parts that wrote themselves as the journey unfolds, the other long-form piece, the eleven-minute Galadrielle, was mostly an improvised jam?

MR: Other than the melody, it was totally improvised...

MR: What’s interesting about Galadrielle is the melody and the lead guitars are definitely the Allman Brothers, but it actually sounds more like the Grateful Dead, and I’m not a huge Grateful Dead fan!

I like some of their stuff but a lot of it just doesn’t connect with me, probably because I like the Allmans so much – their delivery was so assured, and so passionate, whereas the Grateful Dead are more about a slower, [sings] "We’ll get there in the end” approach.

But that’s great too, particularly their 72 live stuff, which is my favourite Grateful Dead period from what I’ve so far discovered.

RM: So you have nothing but a Grateful Dead meets the Allmans melody at this formative stage?

MR: Yeah. The breakdown to Galadrielle is it’s in four sections. There’s an A and B part, or verse and chorus, to the first bit, with a guitar that’s very (Grateful Dead rhythm guitarist) Bob Weir in that pick style, with Allman Brothers over the top.

That goes around three times, and that’s all I had originally, that melody. I actually had a lyric for it but I never sang it. The lyric was [sings] "and her name is Gal-ad-ri-elle" but I left it out.

We went into the Brighton Electric Studios just down the road from me to do the basic tracking for Galadrielle – guitar, bass, drums – and played those bits together.

Then, in my home studio, I replaced some of the guitars and added extra bits, including organ.

On the tune Peach Jam, Ron Millis, another big psyche-head and Allmans nut, plays about half the organ – all the solos are his; I filled in on other bits later.

My organ playing is perfunctory, I’m not really a soloist, but I did play all the organ parts on Galadrielle.

RM: And it works very well in its complementary-to-the-piece fashion.

MR: I guess you can compare it to Gregg Allman’s parts, because he was more of a singer than a keys player.

He wasn’t a virtuoso keyboard player but I loved what he played and he got a really great sound.

I’m comfortable on the organ, but I wouldn’t go any further than that.

RM: Providing contrast to the long-form tracks are two, shorter acoustic based tracks.

The first acoustic tune, Grace, is a jaunty, country-folk arrangement of Amazing Grace, but what I was really drawn to was the old-time charm and poignancy of Derek & Me, written to the memory of your late father.

That tune, for me, conjures fond memories of my own dad, who was one of my best mates; it certainly isn’t a melancholic tune.

MR: No, it’s not melancholy at all, and it is quite poignant. It’s only short but it has a very lyrical melody. There’s a demo of that with me playing it just on the slide, then I did another demo in a different key to better suit the Peach Jam package; that brought it to life.

But it is like you said, an old-time composition, very 1930s. It could be a Noel Coward sort of thing, with lyrics.

RM: When I first played it I immediately got a sense of the 1930s standard Dream a Little Dream of Me, as later made famous by Doris Day among others.

MR: Yeah, it could be on a Doris Day record, too. But then I love all music; Lonnie Johnson is another old-time favourite – he kind of reinvented himself but originally he was more a Chicago blues and jazz type player.

I also think it’s wonderful how he was influential on Django Reinhardt – I thought it was the other way around! They share similar musical DNA and they just had that tempo, you know?

And I wanted that on this tune, something really old-time, because it’s about my dad, Derek.

I loved him dearly and I still think about him – and like you said about your own dad, he was a good mate.

RM: This all make me think that, one, if you were to transport that tune back pre-war to the Great American Songbook composers I’m sure a few of them would say “I’ve got the very lyric for that “and, two, you have a true, old-time sensibility.

MR: Yes, you could take out the melody, embellish the chord sequence, make it longer and add a lyric.

I love all that old-time stuff – there’s another song that affects me much the same way and that’s Miss The Mississippi and You, which I first heard on a Rosanne Cash album [sings] "Miss the Mississippi and you…"

I’ve got a friend here in Brighton and I used to play in her band – she loves all the old-time stuff too; it’s not quite jazz and it’s not quite blues.

RM: To finish our insight into Peach Jam you also include one cover, and the only song with a lyric – Free’s Don’t Say You Love Me, from Fire and Water.

That’s an interesting choice given it’s a slightly deeper cut, but it’s a good, and clever, dovetailing fit alongside your Allmans of 71 and the ‘Dead of 72 homage/ influences.

MR: Don't Say You Love Me is my favourite Free song and one of my favourite songs, full stop.

Everything about it, including the space created, is great, but then Fire and Water is a wonderful record.

It really does illustrate how not to overplay, how to not go crazy with the overdubs – how to just go in and lay everybody low with the great sound of a four-piece band playing in a room.

And never more so than on that song, especially the middle eight, when the backing vocals come in.

My favourite song, ever, is Something by George Harrison, and part of the reason is because of that wonderful middle eight and the emotion that’s captured within it.

RM: One of the finest, uplifting and moving middle eight sections in popular music. One of the greatest ever ballads; truly magical song.

MR: It really is. Don’t Say You Love Me is right up there with Something, where it descends and drops down a tone. I did my version with my guitar through my Leslie speaker, which is something Paul Kossoff did a lot of later but you don’t hear on their first few records. So that was something a little bit different from the original. There’s also a piano on the original, which I thought about doing but I didn’t; the guitar sounded so great through the Leslie speaker that I just left it at that.

I like some of their stuff but a lot of it just doesn’t connect with me, probably because I like the Allmans so much – their delivery was so assured, and so passionate, whereas the Grateful Dead are more about a slower, [sings] "We’ll get there in the end” approach.

But that’s great too, particularly their 72 live stuff, which is my favourite Grateful Dead period from what I’ve so far discovered.

RM: So you have nothing but a Grateful Dead meets the Allmans melody at this formative stage?

MR: Yeah. The breakdown to Galadrielle is it’s in four sections. There’s an A and B part, or verse and chorus, to the first bit, with a guitar that’s very (Grateful Dead rhythm guitarist) Bob Weir in that pick style, with Allman Brothers over the top.

That goes around three times, and that’s all I had originally, that melody. I actually had a lyric for it but I never sang it. The lyric was [sings] "and her name is Gal-ad-ri-elle" but I left it out.

We went into the Brighton Electric Studios just down the road from me to do the basic tracking for Galadrielle – guitar, bass, drums – and played those bits together.

Then, in my home studio, I replaced some of the guitars and added extra bits, including organ.

On the tune Peach Jam, Ron Millis, another big psyche-head and Allmans nut, plays about half the organ – all the solos are his; I filled in on other bits later.

My organ playing is perfunctory, I’m not really a soloist, but I did play all the organ parts on Galadrielle.

RM: And it works very well in its complementary-to-the-piece fashion.

MR: I guess you can compare it to Gregg Allman’s parts, because he was more of a singer than a keys player.

He wasn’t a virtuoso keyboard player but I loved what he played and he got a really great sound.

I’m comfortable on the organ, but I wouldn’t go any further than that.

RM: Providing contrast to the long-form tracks are two, shorter acoustic based tracks.

The first acoustic tune, Grace, is a jaunty, country-folk arrangement of Amazing Grace, but what I was really drawn to was the old-time charm and poignancy of Derek & Me, written to the memory of your late father.

That tune, for me, conjures fond memories of my own dad, who was one of my best mates; it certainly isn’t a melancholic tune.

MR: No, it’s not melancholy at all, and it is quite poignant. It’s only short but it has a very lyrical melody. There’s a demo of that with me playing it just on the slide, then I did another demo in a different key to better suit the Peach Jam package; that brought it to life.

But it is like you said, an old-time composition, very 1930s. It could be a Noel Coward sort of thing, with lyrics.

RM: When I first played it I immediately got a sense of the 1930s standard Dream a Little Dream of Me, as later made famous by Doris Day among others.

MR: Yeah, it could be on a Doris Day record, too. But then I love all music; Lonnie Johnson is another old-time favourite – he kind of reinvented himself but originally he was more a Chicago blues and jazz type player.

I also think it’s wonderful how he was influential on Django Reinhardt – I thought it was the other way around! They share similar musical DNA and they just had that tempo, you know?

And I wanted that on this tune, something really old-time, because it’s about my dad, Derek.

I loved him dearly and I still think about him – and like you said about your own dad, he was a good mate.

RM: This all make me think that, one, if you were to transport that tune back pre-war to the Great American Songbook composers I’m sure a few of them would say “I’ve got the very lyric for that “and, two, you have a true, old-time sensibility.

MR: Yes, you could take out the melody, embellish the chord sequence, make it longer and add a lyric.

I love all that old-time stuff – there’s another song that affects me much the same way and that’s Miss The Mississippi and You, which I first heard on a Rosanne Cash album [sings] "Miss the Mississippi and you…"

I’ve got a friend here in Brighton and I used to play in her band – she loves all the old-time stuff too; it’s not quite jazz and it’s not quite blues.

RM: To finish our insight into Peach Jam you also include one cover, and the only song with a lyric – Free’s Don’t Say You Love Me, from Fire and Water.

That’s an interesting choice given it’s a slightly deeper cut, but it’s a good, and clever, dovetailing fit alongside your Allmans of 71 and the ‘Dead of 72 homage/ influences.

MR: Don't Say You Love Me is my favourite Free song and one of my favourite songs, full stop.

Everything about it, including the space created, is great, but then Fire and Water is a wonderful record.

It really does illustrate how not to overplay, how to not go crazy with the overdubs – how to just go in and lay everybody low with the great sound of a four-piece band playing in a room.

And never more so than on that song, especially the middle eight, when the backing vocals come in.

My favourite song, ever, is Something by George Harrison, and part of the reason is because of that wonderful middle eight and the emotion that’s captured within it.

RM: One of the finest, uplifting and moving middle eight sections in popular music. One of the greatest ever ballads; truly magical song.

MR: It really is. Don’t Say You Love Me is right up there with Something, where it descends and drops down a tone. I did my version with my guitar through my Leslie speaker, which is something Paul Kossoff did a lot of later but you don’t hear on their first few records. So that was something a little bit different from the original. There’s also a piano on the original, which I thought about doing but I didn’t; the guitar sounded so great through the Leslie speaker that I just left it at that.

RM: Vocally, it’s a brave decision when anyone takes on a Paul Rodgers song – because let’s face it no-one else is Paul Rodgers.

But there’s a vulnerability to your vocal on Don't Say You Love Me, particularly on the outros, which adds to the yearning, and honesty, of your version.

MR: I don’t think there’s any other white man alive that sings as well as Paul Rodgers is capable of singing. For me it’s him, followed by Steve Marriot and Stevie Winwood.

There are others, like Steven Stills, Gregg Allman and Joe Cocker, but those first three are my guys.

Also, I don’t think any other white man sounds as much like Otis Redding as Paul Rodgers.

In fact if you’re going to put it into British and American categories then it's Paul Rodgers and, top of the American list, for me, is Otis Redding – he just had such a wonderful, gritty soul.

RM: Agreed, fabulous voice. To go back to your comments on Paul Rodgers, I’d concur and expand.

As regards the singers still plying their trade from what is now known as the classic rock and British blues era of the late sixties and early seventies, Paul Rodgers was then, and is still, the leading light in blues, rock and soul. What he can do with – in general vocal terms, a limited range – is extraordinary.

It’s his delivery, his phrasing; he has an innate soulfulness and lyrical understanding.

MR: His complete ownership of any song, yeah, I agree. I’m not a Paul Rodgers; my voice is strong in certain ways, but it’s more a part of the composite to what I am, which is a singer, a songwriter and a guitar player. When I’m working here in my studio, and over-dubbing, I’m very cautious and very mindful of being authentic, as we said before.

I could sit here and, on a song like Don’t Say You Love Me, drop the vocal in word by word, or phrase by phrase, and present a perfectly in tune, perfectly in time, perfectly recorded song; but that’s not real.

Plenty of people do that, but the people who buy my records, I don’t think that’s what they want, you know? Which is just as well because that’s not me; that’s not what I’m into.

RM: Amen to that; I’ll take flawed, artistic honesty over studio created perfection any day of the music week.

MR: Someone said to me recently at a show “that was a bit sloppy,” to which I said “look man, if you want perfect guitar playing go and hire Dom Martin. I’ve got something else for you, but if that’s not what you want that’s fair enough.”

And I felt quite comfortable with that – maybe it would have been different if I was twenty-four [laughs], but I know me, I know what I want to do and I know how to deliver it.

So I’m cautious not to over-cook it, or over-season the broth.

RM: Absolutely. You have to be true to yourself, you have to be true to your art and you have to be true to your fans, in equal measure. I believe another reason you covered a Free song was as a nod to your northern brother?

MR: Yeah. Paul’s from Middlesbrough and I’m originally from Durham, which is just up the road from Middlesbrough.

And then you have the fact he sounds like Otis Redding and where did Otis make his name? Macon, Georgia. And where did the Allman Brothers live and record in the early seventies? Macon, Georgia.

So it’s all wheels within wheels!

RM: Another instance of those wheels within wheels goes back to your work with Troy Redfern and Jack J Hutchinson as the guitar-powered trio RHR.

Both Troy and Jack are, to my ears, much like yourself, about the passion and honesty and not necessarily the perfection – and much like Peach Jam, but taken even further in instrumental and improvisational terms, you took a very interesting, and brave, approach, on second RHR album Hotel Toledo.

I believe the entire album was recorded live on the floor and improvised?

MR: Kind of, yeah! What we had, or I had, as we talked about before with me and my little recorder app, was a couple of little beats on my phone. I also had maybe three top lines, which was just scraggy guitar playing into the phone. Now, we were doing about five gigs from, I think the Wednesday of one week to the Tuesday of the next; something like that.

On the Monday, near the end of that run, we went to Brighton Electric Studios and set up live with my good mate and producer "Win" – Paul Winstanley.

Win actually did Troy’s last record as result of working with him on Hotel Toledo.

We set up, and all we had were those little ideas and couple of bits we had been trying at soundchecks. Second track in, Pintura de Luna, which in English is Picture of the Moon – we titled all the tracks in Spanish – has two bits we’d been putting in to my RHR song She Painted the Moon, live. It was like a little written jam.

So that’s what we did with Pintura de Luna, but really all we knew were the chords; we also talked to our drummer Darren Lee, who’s been my drummer for years, about doing the double-time bit, but that was it.

The only other one where we had something was Tres Hermanos, Three Brothers, where I had a Hendrix thing to start it off, then it goes into a shuffle. I had that, but everything else was improvised on the fly.

The first track, El Sueña del Águila, A Dream of Eagles, which is about twenty minutes long – that was literally written on the shop floor, note by note; I think it was Troy that started it off, just after having finished tuning.

The unedited version probably went on for about thirty-five minutes, but Win edited it by just taking out the bits where we started drifting; but nothing was replaced or repaired; nothing was corrected; we just shortened it.

So, yes, it was almost completely improvised and that was exactly what we wanted to do; that was the entire idea behind it, but we didn’t even know if we were going to release a record of it.

It all started when we were sitting at an airport, having done a gig in Germany, waiting for the flight home. Troy and I were talking and enthusing about the idea of doing a totally improvised live record; he’s into quite avant-garde stuff – Zoot Horn Rollo, Captain Beefheart, Zappa, many more.

Me, not so much, but I really like improvising and playing with soundscapes – on that first track, A Dream of Eagles, I’m playing a drill [laughs]. I put the drill up next to the pickups of my Strat and [mimics] zreeeemm! and then play it through my copycat delay – it was just a great opportunity to bring all that stuff in.

It’s a bit like some of the Pink Floyd jams as well, although I don’t know them that well; but it definitely has that feel.

RM: It’s a remarkable record in many ways and, rather obviously, very organic.

Some of it sounds exactly as it is – improvised – but there are also some very cohesive pieces in that anyone not in the know would readily assume were rehearsed, or even fully written instrumental tunes…

But there’s a vulnerability to your vocal on Don't Say You Love Me, particularly on the outros, which adds to the yearning, and honesty, of your version.

MR: I don’t think there’s any other white man alive that sings as well as Paul Rodgers is capable of singing. For me it’s him, followed by Steve Marriot and Stevie Winwood.

There are others, like Steven Stills, Gregg Allman and Joe Cocker, but those first three are my guys.

Also, I don’t think any other white man sounds as much like Otis Redding as Paul Rodgers.

In fact if you’re going to put it into British and American categories then it's Paul Rodgers and, top of the American list, for me, is Otis Redding – he just had such a wonderful, gritty soul.

RM: Agreed, fabulous voice. To go back to your comments on Paul Rodgers, I’d concur and expand.

As regards the singers still plying their trade from what is now known as the classic rock and British blues era of the late sixties and early seventies, Paul Rodgers was then, and is still, the leading light in blues, rock and soul. What he can do with – in general vocal terms, a limited range – is extraordinary.

It’s his delivery, his phrasing; he has an innate soulfulness and lyrical understanding.

MR: His complete ownership of any song, yeah, I agree. I’m not a Paul Rodgers; my voice is strong in certain ways, but it’s more a part of the composite to what I am, which is a singer, a songwriter and a guitar player. When I’m working here in my studio, and over-dubbing, I’m very cautious and very mindful of being authentic, as we said before.

I could sit here and, on a song like Don’t Say You Love Me, drop the vocal in word by word, or phrase by phrase, and present a perfectly in tune, perfectly in time, perfectly recorded song; but that’s not real.

Plenty of people do that, but the people who buy my records, I don’t think that’s what they want, you know? Which is just as well because that’s not me; that’s not what I’m into.

RM: Amen to that; I’ll take flawed, artistic honesty over studio created perfection any day of the music week.

MR: Someone said to me recently at a show “that was a bit sloppy,” to which I said “look man, if you want perfect guitar playing go and hire Dom Martin. I’ve got something else for you, but if that’s not what you want that’s fair enough.”

And I felt quite comfortable with that – maybe it would have been different if I was twenty-four [laughs], but I know me, I know what I want to do and I know how to deliver it.

So I’m cautious not to over-cook it, or over-season the broth.

RM: Absolutely. You have to be true to yourself, you have to be true to your art and you have to be true to your fans, in equal measure. I believe another reason you covered a Free song was as a nod to your northern brother?

MR: Yeah. Paul’s from Middlesbrough and I’m originally from Durham, which is just up the road from Middlesbrough.

And then you have the fact he sounds like Otis Redding and where did Otis make his name? Macon, Georgia. And where did the Allman Brothers live and record in the early seventies? Macon, Georgia.

So it’s all wheels within wheels!

RM: Another instance of those wheels within wheels goes back to your work with Troy Redfern and Jack J Hutchinson as the guitar-powered trio RHR.

Both Troy and Jack are, to my ears, much like yourself, about the passion and honesty and not necessarily the perfection – and much like Peach Jam, but taken even further in instrumental and improvisational terms, you took a very interesting, and brave, approach, on second RHR album Hotel Toledo.

I believe the entire album was recorded live on the floor and improvised?

MR: Kind of, yeah! What we had, or I had, as we talked about before with me and my little recorder app, was a couple of little beats on my phone. I also had maybe three top lines, which was just scraggy guitar playing into the phone. Now, we were doing about five gigs from, I think the Wednesday of one week to the Tuesday of the next; something like that.

On the Monday, near the end of that run, we went to Brighton Electric Studios and set up live with my good mate and producer "Win" – Paul Winstanley.

Win actually did Troy’s last record as result of working with him on Hotel Toledo.

We set up, and all we had were those little ideas and couple of bits we had been trying at soundchecks. Second track in, Pintura de Luna, which in English is Picture of the Moon – we titled all the tracks in Spanish – has two bits we’d been putting in to my RHR song She Painted the Moon, live. It was like a little written jam.

So that’s what we did with Pintura de Luna, but really all we knew were the chords; we also talked to our drummer Darren Lee, who’s been my drummer for years, about doing the double-time bit, but that was it.

The only other one where we had something was Tres Hermanos, Three Brothers, where I had a Hendrix thing to start it off, then it goes into a shuffle. I had that, but everything else was improvised on the fly.

The first track, El Sueña del Águila, A Dream of Eagles, which is about twenty minutes long – that was literally written on the shop floor, note by note; I think it was Troy that started it off, just after having finished tuning.

The unedited version probably went on for about thirty-five minutes, but Win edited it by just taking out the bits where we started drifting; but nothing was replaced or repaired; nothing was corrected; we just shortened it.

So, yes, it was almost completely improvised and that was exactly what we wanted to do; that was the entire idea behind it, but we didn’t even know if we were going to release a record of it.

It all started when we were sitting at an airport, having done a gig in Germany, waiting for the flight home. Troy and I were talking and enthusing about the idea of doing a totally improvised live record; he’s into quite avant-garde stuff – Zoot Horn Rollo, Captain Beefheart, Zappa, many more.

Me, not so much, but I really like improvising and playing with soundscapes – on that first track, A Dream of Eagles, I’m playing a drill [laughs]. I put the drill up next to the pickups of my Strat and [mimics] zreeeemm! and then play it through my copycat delay – it was just a great opportunity to bring all that stuff in.

It’s a bit like some of the Pink Floyd jams as well, although I don’t know them that well; but it definitely has that feel.

RM: It’s a remarkable record in many ways and, rather obviously, very organic.

Some of it sounds exactly as it is – improvised – but there are also some very cohesive pieces in that anyone not in the know would readily assume were rehearsed, or even fully written instrumental tunes…

RM: It has to be immensely satisfying when you have musicians as mates who know each other so well that you can produce something like that, pretty much from scratch.

MR: It was good, yeah. Playing with those guys was really very easy because we were all confident enough to roll with the vibe; we were all very strong players who had a different enough approach in their sounds so as not to get in each other’s way – and live we had not one but two really good rhythm sections who were absolutely solid and knew all the stuff.

I actually thought we would still be doing it, to be honest. I thought we would do a tour and a record each year, and hopefully keep going, but Jack wanted to focus on his solo career.

Then Covid came and caught us out, and now Troy’s solo career has taken off.

I put a lot of work into RHR because I really wanted it to work, and I’ve always felt it was the perfect line-up, kinda like a Crosby Stills and Nash thing – three singers, that can also play well, and maybe one of them can also play keyboards; then you can have three guitars, or two guitars and a keyboard.

Three lead instruments and three strong vocals would be my ideal platform.

RM: So you would consider that sort of triumvirate again?

MR: Well I don’t want to give too much away at this stage but I’m tracking at the moment, in my studio, comp’ing some stuff together for my next record, which will come out next year.

To play this new stuff will take three guitar players – now I didn’t write it for RHR, not at all, but it will take three guitarists to recreate the kind of thing that I’m doing now.

Bits of it sound like AC/DC with Derek Trucks sitting in, and Jack’s coming down here to sing a bunch of harmonies for the new record, so we might even end up doing something else together – we’ve always been good mates, even before the RHR stuff.

RM: Colour me, and I suspect your fanbase, more than a little intrigued; I look forward to hearing what you come up with next – meanwhile thanks so much for sitting in with FabricationsHQ, Mike.

This has been, dare I say, just Peachy.

MR: [laughs] It’s been great to catch up and chat with you, Ross, I’ve really enjoyed it. Take care!

MR: It was good, yeah. Playing with those guys was really very easy because we were all confident enough to roll with the vibe; we were all very strong players who had a different enough approach in their sounds so as not to get in each other’s way – and live we had not one but two really good rhythm sections who were absolutely solid and knew all the stuff.

I actually thought we would still be doing it, to be honest. I thought we would do a tour and a record each year, and hopefully keep going, but Jack wanted to focus on his solo career.

Then Covid came and caught us out, and now Troy’s solo career has taken off.

I put a lot of work into RHR because I really wanted it to work, and I’ve always felt it was the perfect line-up, kinda like a Crosby Stills and Nash thing – three singers, that can also play well, and maybe one of them can also play keyboards; then you can have three guitars, or two guitars and a keyboard.

Three lead instruments and three strong vocals would be my ideal platform.

RM: So you would consider that sort of triumvirate again?

MR: Well I don’t want to give too much away at this stage but I’m tracking at the moment, in my studio, comp’ing some stuff together for my next record, which will come out next year.

To play this new stuff will take three guitar players – now I didn’t write it for RHR, not at all, but it will take three guitarists to recreate the kind of thing that I’m doing now.

Bits of it sound like AC/DC with Derek Trucks sitting in, and Jack’s coming down here to sing a bunch of harmonies for the new record, so we might even end up doing something else together – we’ve always been good mates, even before the RHR stuff.

RM: Colour me, and I suspect your fanbase, more than a little intrigued; I look forward to hearing what you come up with next – meanwhile thanks so much for sitting in with FabricationsHQ, Mike.

This has been, dare I say, just Peachy.

MR: [laughs] It’s been great to catch up and chat with you, Ross, I’ve really enjoyed it. Take care!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Mike Ross

July 2022

Peach Jam is out now.

Digital: https://themikerossband.bandcamp.com/album/peach-jam-2

Clear Vinyl edition: https://shop.mikerossmusic.co.uk/product/peach-jam-12-album-picture-disc-pre-order

Mike Ross digital catalogue: https://themikerossband.bandcamp.com/

Website: https://www.mikerossmusic.co.uk/

Photo credits: Adam Kennedy (portrait/ press shots); Haluk Gurer (live photo)

Muirsical Conversation with Mike Ross

July 2022

Peach Jam is out now.

Digital: https://themikerossband.bandcamp.com/album/peach-jam-2

Clear Vinyl edition: https://shop.mikerossmusic.co.uk/product/peach-jam-12-album-picture-disc-pre-order

Mike Ross digital catalogue: https://themikerossband.bandcamp.com/

Website: https://www.mikerossmusic.co.uk/

Photo credits: Adam Kennedy (portrait/ press shots); Haluk Gurer (live photo)