Playing With Passion

Muirsical Conversation with John Verity

Muirsical Conversation with John Verity

In 2020 rock and blues singer-guitarist-songwriter John Verity celebrated a fifty year anniversary.

Verity’s career as a musician goes back further than half-a-century but 1970 is the year that established him as a solo artist and band leader, writing and playing original material.

Within that fifty years, outside of the solo career, there was also a notable stint with Argent, co-forming Argent off-shoot band Phoenix, a host of session and production work (including Saxon’s debut album) and collaborations with the likes of heavy pop-rock band Charlie and ex Sweet front man Brian Connolly, among many others.

2020 should have been a 50th Anniversary Tour year for John Verity but the Covid-19 pandemic laid low any and all such plans.

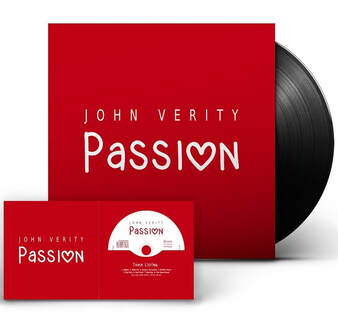

However, by way of compensation, current album Passion is one of John Verity’s strongest ever albums; it’s also, unquestionably, his most all-encompassing.

Semi-autobiographical in nature, a number of songs on Passion play homage to John Verity’s influences while others lyrically emphasise his thoughts on current, state-of-the-world, affairs.

John Verity sat down with FabricationsHQ for an extended, feature length conversation that covered all the musical bases from a highly interesting and pivotal 1970 through to the satisfying blues rock niche John Verity has carved for himself in the 21st century.

But the conversation started fifty years earlier…

Ross Muir: 1970 is the year that starts this 50th anniversary you’re currently celebrating as a solo artist, delivering your own material.

You were active prior to 1970, but primarily as a gigging musician-for-hire with different bands.

John Verity: Yeah. that's right The way to describe it best is to go back to 1969.

I had ended up in America that year with a band I was in and we just started to do original stuff, instead of the run of the mill covers of that time.

We were then discovered by an American promoter while we were playing in the Bahamas of all places!

There was a rock club on Grand Bahama in Freeport; in the late sixties the guy that owned it, Dave Fishman from New York, sussed it was close enough to the Florida coast to get American college kids over during the summer so he started booking English bands.

He started to work with an agency in England, that we just happened to be signed to, and they started shipping in English bands every summer.

We went over to do a residency for a few weeks over the summer but ended up staying we were so popular; but that was as much to do with being English as anything else.

About six months into our extended stay this guy approached us, who was over on holiday from Miami, to see if we would go over there. What do you think we said? [laughter].

That was the start of it all really; we went across to America and through that promoter we got all the big American gigs I talk about in my bio – the Hendrix gig, the Janis Joplin gig, Canned Heat, big names like that.

That promoter and his partner also had one of the major PA companies back then so they used to look after all the big touring bands that came through; we became the ideal opportunity for him to get one of his own bands on to those gigs. That’s what kicked everything of for us, and me, really.

RM: That’s a really interesting story. I also have to say working the Bahamas before being taken across to the eastern seaboard of America to open for the likes of Jimi Hendrix isn’t a bad gig, John.

JV: [laughs] It was a fantastic time. I was about nineteen when we first went over there and the Hendrix gig was two days after my twenty-first birthday!

The reason I call this current period my fiftieth anniversary is not because it’s fifty years since I started playing, which it’s not, as you rightly said, but it is the fiftieth anniversary of when I started to do my own stuff, rather than the hired hand you mentioned.

RM: Yes, 1970 is when you start to musically and lyrically express yourself as John Verity the solo, or own band, artist. This would also be when you formed the band called Tunnel, who played America?

JV: Yes, it was, but that name was a bit cheesy! [laughs].

Around that time there were lot of bands who were, well, prog rock really, but the term used to describe those acts back then was underground bands so, underground… tunnel! [laughs].

RM: Cheesy point well taken, but establishing a name helps to get you out there, selling your own wares so to speak. And name-wise, I’ve heard a lot worse…

JV: Oh, me too [laughs] but band names are a nightmare to be honest; that’s why I just ended up being the John Verity Band!

When we were trying to find a name for the band I co-formed at the end of Argent with Bob Henrit and Jim Rodford, we had Phoenix, but that was just the name of the album.

We had actually started with Henrit Rodford & Verity, as in Emerson Lake & Palmer, because we thought with our ex Argent profile it would be better to use our name.

But album title of Phoenix – because we were rising from the ashes of Argent – was what the press latched on to as the band name; the record company weren’t going to argue with that!

Verity’s career as a musician goes back further than half-a-century but 1970 is the year that established him as a solo artist and band leader, writing and playing original material.

Within that fifty years, outside of the solo career, there was also a notable stint with Argent, co-forming Argent off-shoot band Phoenix, a host of session and production work (including Saxon’s debut album) and collaborations with the likes of heavy pop-rock band Charlie and ex Sweet front man Brian Connolly, among many others.

2020 should have been a 50th Anniversary Tour year for John Verity but the Covid-19 pandemic laid low any and all such plans.

However, by way of compensation, current album Passion is one of John Verity’s strongest ever albums; it’s also, unquestionably, his most all-encompassing.

Semi-autobiographical in nature, a number of songs on Passion play homage to John Verity’s influences while others lyrically emphasise his thoughts on current, state-of-the-world, affairs.

John Verity sat down with FabricationsHQ for an extended, feature length conversation that covered all the musical bases from a highly interesting and pivotal 1970 through to the satisfying blues rock niche John Verity has carved for himself in the 21st century.

But the conversation started fifty years earlier…

Ross Muir: 1970 is the year that starts this 50th anniversary you’re currently celebrating as a solo artist, delivering your own material.

You were active prior to 1970, but primarily as a gigging musician-for-hire with different bands.

John Verity: Yeah. that's right The way to describe it best is to go back to 1969.

I had ended up in America that year with a band I was in and we just started to do original stuff, instead of the run of the mill covers of that time.

We were then discovered by an American promoter while we were playing in the Bahamas of all places!

There was a rock club on Grand Bahama in Freeport; in the late sixties the guy that owned it, Dave Fishman from New York, sussed it was close enough to the Florida coast to get American college kids over during the summer so he started booking English bands.

He started to work with an agency in England, that we just happened to be signed to, and they started shipping in English bands every summer.

We went over to do a residency for a few weeks over the summer but ended up staying we were so popular; but that was as much to do with being English as anything else.

About six months into our extended stay this guy approached us, who was over on holiday from Miami, to see if we would go over there. What do you think we said? [laughter].

That was the start of it all really; we went across to America and through that promoter we got all the big American gigs I talk about in my bio – the Hendrix gig, the Janis Joplin gig, Canned Heat, big names like that.

That promoter and his partner also had one of the major PA companies back then so they used to look after all the big touring bands that came through; we became the ideal opportunity for him to get one of his own bands on to those gigs. That’s what kicked everything of for us, and me, really.

RM: That’s a really interesting story. I also have to say working the Bahamas before being taken across to the eastern seaboard of America to open for the likes of Jimi Hendrix isn’t a bad gig, John.

JV: [laughs] It was a fantastic time. I was about nineteen when we first went over there and the Hendrix gig was two days after my twenty-first birthday!

The reason I call this current period my fiftieth anniversary is not because it’s fifty years since I started playing, which it’s not, as you rightly said, but it is the fiftieth anniversary of when I started to do my own stuff, rather than the hired hand you mentioned.

RM: Yes, 1970 is when you start to musically and lyrically express yourself as John Verity the solo, or own band, artist. This would also be when you formed the band called Tunnel, who played America?

JV: Yes, it was, but that name was a bit cheesy! [laughs].

Around that time there were lot of bands who were, well, prog rock really, but the term used to describe those acts back then was underground bands so, underground… tunnel! [laughs].

RM: Cheesy point well taken, but establishing a name helps to get you out there, selling your own wares so to speak. And name-wise, I’ve heard a lot worse…

JV: Oh, me too [laughs] but band names are a nightmare to be honest; that’s why I just ended up being the John Verity Band!

When we were trying to find a name for the band I co-formed at the end of Argent with Bob Henrit and Jim Rodford, we had Phoenix, but that was just the name of the album.

We had actually started with Henrit Rodford & Verity, as in Emerson Lake & Palmer, because we thought with our ex Argent profile it would be better to use our name.

But album title of Phoenix – because we were rising from the ashes of Argent – was what the press latched on to as the band name; the record company weren’t going to argue with that!

RM: Interesting you mention Argent because just as you are looking to make inroads post-Tunnel as the John Verity Band and the self-titled debut album, Argent come calling.

Was there any pressure at all in having to replace Russ Ballard?

JV: Not really; in fact it seems it was Russell who suggested they call me – I had just been on tour with Argent, opening for them.

When Russell announced he was leaving the band, partly to pursue a solo and songwriting career but also, I think, just to take some time off, he suggested me.

Rod Argent really wanted to do the jazz-rock thing and Russell was still coming up with the commercial sounding hits.

In fact Argent’s last single, Thunder and Lightning, written by Russell when he was still with them, just didn’t fit with what they were then doing. When they played it on stage it stood out like a sore thumb, because it just wasn’t what they were about any more.

But CBS were very pro Russell because they liked the hits, of course! [laughs]

RM: Major labels, especially in that era, were always looking for the next hit from the bands on their books but, yes, absolutely, Argent were heading in a very different direction by then.

The albums you featured on, Circus and Counterpoints, were very jazz-rock/ rock-fusion orientated.

JV: I came in around the middle of Circus; in fact it was nearly finished by the time I joined the band.

I actually think, not that anyone has ever said this to me, the band were going to continue on as a four-piece when they brought in a guitarist called John Grimaldi for Circus.

I do think the intention was to have that as the new line-up – Rod, Bob Henrit, Jim Rodford and John – but when it came time to think about the next tour the band weren’t strong enough vocally.

Again, no-one has ever told me that, but I do think that was the case.

They were perfectly happy on the guitar front with John – in fact I had to fight to be able to play!

I had to say "look, I’m not a stand up the front singer; that’s not what I do. "

I did give in and do a few songs like that, but that was more pressure from the record company because they wanted that look – but it wasn’t long before I was grabbing my guitar again! [laughs].

RM: From Argent to Phoenix, whom you mentioned, then on to a short stint with Charlie.

The album you feature on, 1981’s Good Morning America – a title that tells you where it was marketed toward – is a really good, melodic hard pop-rock album, reminiscent of early Loverboy and Toto.

JV: The Charlie situation was a bit or weird one to be honest! [laughs].

We, Phoenix, had the same management as Charlie and they were struggling a bit at the time – but then so were we, wondering what to do for the next album. So the master plan became that we would help each other.

Their front man Terry Thomas, a great writer as well as a great singer, was going to get involved with us and give us a hand with our next album – and I was going to give them a hand with theirs.

Terry would also produce the next Phoenix album with me and I was going to co-produce the next Charlie album, with Terry.

But, as we got to working in the studio our management said "why don’t we just amalgamate the two bands?" That came about because I had said Bob Henrit would be better on the drums on a couple of Charlie tracks than their regular drummer; then Terry had asked me if I would do lead vocals on a couple of their other songs – and remember he’s the lead vocalist! [laughs].

But as it turned out he had written the songs in my range; they weren’t in his range at all.

So to cut an even longer story short we decided to amalgamate the two bands, because at the time the UK market was miles away from the stuff we were doing.

The New Wave thing was still happening in the UK so America seemed the better market to go for – and as Charlie had the more recent success in America the band was called Charlie, even though it was an amalgam of the two bands.

RM: An amalgam that worked extremely well, proven by songs such as the title track and Roll The Dice, a track you revisited a few years later on your 1985 solo album, Truth of the Matter.

Was there any pressure at all in having to replace Russ Ballard?

JV: Not really; in fact it seems it was Russell who suggested they call me – I had just been on tour with Argent, opening for them.

When Russell announced he was leaving the band, partly to pursue a solo and songwriting career but also, I think, just to take some time off, he suggested me.

Rod Argent really wanted to do the jazz-rock thing and Russell was still coming up with the commercial sounding hits.

In fact Argent’s last single, Thunder and Lightning, written by Russell when he was still with them, just didn’t fit with what they were then doing. When they played it on stage it stood out like a sore thumb, because it just wasn’t what they were about any more.

But CBS were very pro Russell because they liked the hits, of course! [laughs]

RM: Major labels, especially in that era, were always looking for the next hit from the bands on their books but, yes, absolutely, Argent were heading in a very different direction by then.

The albums you featured on, Circus and Counterpoints, were very jazz-rock/ rock-fusion orientated.

JV: I came in around the middle of Circus; in fact it was nearly finished by the time I joined the band.

I actually think, not that anyone has ever said this to me, the band were going to continue on as a four-piece when they brought in a guitarist called John Grimaldi for Circus.

I do think the intention was to have that as the new line-up – Rod, Bob Henrit, Jim Rodford and John – but when it came time to think about the next tour the band weren’t strong enough vocally.

Again, no-one has ever told me that, but I do think that was the case.

They were perfectly happy on the guitar front with John – in fact I had to fight to be able to play!

I had to say "look, I’m not a stand up the front singer; that’s not what I do. "

I did give in and do a few songs like that, but that was more pressure from the record company because they wanted that look – but it wasn’t long before I was grabbing my guitar again! [laughs].

RM: From Argent to Phoenix, whom you mentioned, then on to a short stint with Charlie.

The album you feature on, 1981’s Good Morning America – a title that tells you where it was marketed toward – is a really good, melodic hard pop-rock album, reminiscent of early Loverboy and Toto.

JV: The Charlie situation was a bit or weird one to be honest! [laughs].

We, Phoenix, had the same management as Charlie and they were struggling a bit at the time – but then so were we, wondering what to do for the next album. So the master plan became that we would help each other.

Their front man Terry Thomas, a great writer as well as a great singer, was going to get involved with us and give us a hand with our next album – and I was going to give them a hand with theirs.

Terry would also produce the next Phoenix album with me and I was going to co-produce the next Charlie album, with Terry.

But, as we got to working in the studio our management said "why don’t we just amalgamate the two bands?" That came about because I had said Bob Henrit would be better on the drums on a couple of Charlie tracks than their regular drummer; then Terry had asked me if I would do lead vocals on a couple of their other songs – and remember he’s the lead vocalist! [laughs].

But as it turned out he had written the songs in my range; they weren’t in his range at all.

So to cut an even longer story short we decided to amalgamate the two bands, because at the time the UK market was miles away from the stuff we were doing.

The New Wave thing was still happening in the UK so America seemed the better market to go for – and as Charlie had the more recent success in America the band was called Charlie, even though it was an amalgam of the two bands.

RM: An amalgam that worked extremely well, proven by songs such as the title track and Roll The Dice, a track you revisited a few years later on your 1985 solo album, Truth of the Matter.

RM: Your short stint with Charlie was followed by a number of session, vocal or producing duties with the likes of Motorhead, Ringo Starr and Colin Blunstone, to name but three.

You also worked with the Brian Connolly Band before resuming your solo career I believe.

JV: I did work with Brian Connolly, yes, although that was more of a project than a band.

I was initially asked to produce Brian so, of course, brought in my own musicians – that’s what you tend to do when you’re producing people.

So I brought in Bob Henrit, my go-to drummer, and my mate Terry Utley, another Bradford lad and bassist with Smokie. That was only supposed to be a studio line-up for recording but the record company wanted Brian to go out on the road and decided to use the same people.

So it wasn’t actually a band, as such; we did it because by then Brian and I had become mates.

He just wanted someone to lean on, really.

RM: The resumption of your solo career started with Interrupted Journey; that's a really great 80s rock album.

It’s also well named, given the initial plans for a solo career had been scuppered almost before they started when Argent came calling…

JV: It is well named but that had nothing to do with how the title came about!

I was actually in the middle of recording that album when the call to help Brian came, but I didn’t have a title at that stage. All I had was a working title – Bob Henrit always used to say that sometimes I sang so high only dogs could hear me [laughter] so the working title was Music For Dogs!

But, when it came to doing the artwork for the album, the record company found a painting that became the cover. The painting was called Interrupted Journey; that’s where the name actually came from.

RM: That set you on your way to what has been pretty much an uninterrupted solo journey ever since, with an impressive and fairly large back catalogue.

Something that has become a bit of a trademark since Interrupted Journey is that you tend to record and feature a cover or two; that’s also reflected in your live sets.

JV: For me, Ross, it’s about songs, first and foremost; there are some great songs out there to play.

I think it’s a bit anal to say you only do your own material when there are just so many great songs out there you can play.

When we were doing Interrupted Journey I was actively looking for some strong songs to cover and we ended up doing a version of Stay With Me Baby, which is one of my favourite songs of all time.

RM: It’s a fabulous song; a true classic. You delivered a great version.

You also worked with the Brian Connolly Band before resuming your solo career I believe.

JV: I did work with Brian Connolly, yes, although that was more of a project than a band.

I was initially asked to produce Brian so, of course, brought in my own musicians – that’s what you tend to do when you’re producing people.

So I brought in Bob Henrit, my go-to drummer, and my mate Terry Utley, another Bradford lad and bassist with Smokie. That was only supposed to be a studio line-up for recording but the record company wanted Brian to go out on the road and decided to use the same people.

So it wasn’t actually a band, as such; we did it because by then Brian and I had become mates.

He just wanted someone to lean on, really.

RM: The resumption of your solo career started with Interrupted Journey; that's a really great 80s rock album.

It’s also well named, given the initial plans for a solo career had been scuppered almost before they started when Argent came calling…

JV: It is well named but that had nothing to do with how the title came about!

I was actually in the middle of recording that album when the call to help Brian came, but I didn’t have a title at that stage. All I had was a working title – Bob Henrit always used to say that sometimes I sang so high only dogs could hear me [laughter] so the working title was Music For Dogs!

But, when it came to doing the artwork for the album, the record company found a painting that became the cover. The painting was called Interrupted Journey; that’s where the name actually came from.

RM: That set you on your way to what has been pretty much an uninterrupted solo journey ever since, with an impressive and fairly large back catalogue.

Something that has become a bit of a trademark since Interrupted Journey is that you tend to record and feature a cover or two; that’s also reflected in your live sets.

JV: For me, Ross, it’s about songs, first and foremost; there are some great songs out there to play.

I think it’s a bit anal to say you only do your own material when there are just so many great songs out there you can play.

When we were doing Interrupted Journey I was actively looking for some strong songs to cover and we ended up doing a version of Stay With Me Baby, which is one of my favourite songs of all time.

RM: It’s a fabulous song; a true classic. You delivered a great version.

JV: I should also say it was Stay With Me Baby that made me want to be a singer!

In my early career I was never allowed to be the singer in the band because of this high voice – in the sixties that was really unfashionable.

The groups I played in back then were more like soul bands, so people wanted to hear more of an Otis Redding or Wilson Pickett kind of voice, which is not close to my own voice [laughs].

But in the later sixties I was a guitarist for a guy called Dave Berry, who you may remember?

RM: I do indeed.

JV: One of the gigs I did with Dave, around 1968 or 1969 – just prior to Tunnel – was at the Redcar Jazz Club, opening for Terry Reid.

Now Terry had, back then, this very high voice. He had also, of course, been first choice for the Zeppelin gig.

That gig sticks in my mind because two things happened in very quick succession.

First, we did that gig with Terry and as I stood there watching him I thought to myself "I can be a singer! My voice is just like this guy’s!"

Secondly, he did a version of Stay With Me Baby, which just bowled me over.

Then of course the first Led Zeppelin album came out and there’s Robert Plant singing in that upper register as well! So that did it for me [laughs].

This all coincided with Tunnel forming; it was exactly the right time for me to start writing my own stuff and to get some singing under my belt.

RM: Which takes us back to America, where it all started for John Verity.

That American period was relatively short-lived, however.

JV: Yes, but a few things happened in America that made the other guys in the band want to split.

For example we found out that our manager was a major drug dealer; a lot of the drugs were coming in to America from the islands and that’s where all money was coming from to finance us!

We found out through a series of weird events – guns were involved at one point – it was like being in a film!

After one particular incident we had a band meeting an all the other guys said "look, we want to leave."

I tried to reason with them and said "let’s talk to him and tell him that he has to stay completely away from us from now on, even if we have to be moved to live somewhere else, and be completely removed from it all.

Let’s just keep it completely professional and it’ll be fine."

We had some really amazing gigs in the diary and I didn’t want to walk away from that, so everyone agreed and we all went to our beds – we all lived together in the same apartment.

But when I got up the next morning everybody had gone! Turns out they were just humouring me! [laughs]

RM: The moonlit flit writ large.

JV: Yeah, exactly; they all just legged it! I went to see our manager to tell him what had happened and was he really, genuinely upset – and I, foolishly, said "don’t worry, I’ll form a band."

We put an ad in the free ad papers and started auditioning people because we had a really big gig coming up with Mountain, in front of a very large audience – and I hadn’t even sung a full set yet; I had only, to that point, sung a few songs in any set.

So I found a bass player and a drummer and we opened for Mountain in front of four or five thousand people, and that’s how my first full gig, fronting and singing for a band, came about!

It was a baptism of fire, but that sort of thing definitely makes you pull your finger out!

RM: There are many instances of stories told backstage stay backstage but the wonderful anecdotes I’ve heard from you in the past, and the one you’ve just told, leads to the obvious question:

Surely you should be writing a book?

JV: Yeah, I know, people say that to me all the time!

The problem is I don’t have a very good memory for tying all the things together.

When I read other people’s books – like Keith Richards' book – he remembers all this stuff about when he was a young kid, but I don’t remember anything! [laughs]

RM: While you might not be putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard, you still put fine voice to your songs.

You are still in great form vocally with a very strong, clean upper register – I’m presuming you look after the voice or exercise the vocal chords routinely?

JV: I sing every day. Because of where we are, we don’t really have any neighbours, so I can sing properly and practice at, basically, stage volume.

In fact I can really go for it! [laughs].

And because it’s a muscle, there’s no point in pussyfooting around with it – you have to work it.

RM: You've always been very off-handed about your guitar playing, that you "just play and see what comes out" to paraphrase your good self, but you have a very natural feel on the instrument, which is primarily your Fret King Black Label Corona signature guitar.

You can give it the full Hendrix when required but you’re an expressive and melodic player; one who knows the space between the notes is as important as the notes themselves – all of which is showcased to fine effect on latest album, Passion.

JV: Well first of all, thank you very much. I must admit the whole shredding thing, that’s happening again, does my head in; I just can’t listen to it! [laughs]

I know artists are always going to say their latest album is their best album but I do honestly believe Passion is my best album – which is great considering it’s also the one that celebrates the fifty years.

I’m very pleased with Passion.

RM: It’s also a musical autobiography; each song tells a tale about you, your influences, or lyrically emphasises something you are passionate about.

That autobiographical slant is there from the get-go on opening number Higher; lyrically it tells the tale of a young boy dreaming of guitars and rock 'n' roll success…

JV: That’s it exactly; it is me looking in the window at that guitar – I’m really glad you get that because that’s the story I was trying to get across on that song.

RM: It’s also interesting that Wise Up, one of the weightier songs on Passion, became so lyrically accurate and poignant, from a political and social unrest point of view, within weeks of the album being released.

JV: Well, I have to admit, while it’s partly accidental in its timing, I did kind of see the writing on the wall…

In my early career I was never allowed to be the singer in the band because of this high voice – in the sixties that was really unfashionable.

The groups I played in back then were more like soul bands, so people wanted to hear more of an Otis Redding or Wilson Pickett kind of voice, which is not close to my own voice [laughs].

But in the later sixties I was a guitarist for a guy called Dave Berry, who you may remember?

RM: I do indeed.

JV: One of the gigs I did with Dave, around 1968 or 1969 – just prior to Tunnel – was at the Redcar Jazz Club, opening for Terry Reid.

Now Terry had, back then, this very high voice. He had also, of course, been first choice for the Zeppelin gig.

That gig sticks in my mind because two things happened in very quick succession.

First, we did that gig with Terry and as I stood there watching him I thought to myself "I can be a singer! My voice is just like this guy’s!"

Secondly, he did a version of Stay With Me Baby, which just bowled me over.

Then of course the first Led Zeppelin album came out and there’s Robert Plant singing in that upper register as well! So that did it for me [laughs].

This all coincided with Tunnel forming; it was exactly the right time for me to start writing my own stuff and to get some singing under my belt.

RM: Which takes us back to America, where it all started for John Verity.

That American period was relatively short-lived, however.

JV: Yes, but a few things happened in America that made the other guys in the band want to split.

For example we found out that our manager was a major drug dealer; a lot of the drugs were coming in to America from the islands and that’s where all money was coming from to finance us!

We found out through a series of weird events – guns were involved at one point – it was like being in a film!

After one particular incident we had a band meeting an all the other guys said "look, we want to leave."

I tried to reason with them and said "let’s talk to him and tell him that he has to stay completely away from us from now on, even if we have to be moved to live somewhere else, and be completely removed from it all.

Let’s just keep it completely professional and it’ll be fine."

We had some really amazing gigs in the diary and I didn’t want to walk away from that, so everyone agreed and we all went to our beds – we all lived together in the same apartment.

But when I got up the next morning everybody had gone! Turns out they were just humouring me! [laughs]

RM: The moonlit flit writ large.

JV: Yeah, exactly; they all just legged it! I went to see our manager to tell him what had happened and was he really, genuinely upset – and I, foolishly, said "don’t worry, I’ll form a band."

We put an ad in the free ad papers and started auditioning people because we had a really big gig coming up with Mountain, in front of a very large audience – and I hadn’t even sung a full set yet; I had only, to that point, sung a few songs in any set.

So I found a bass player and a drummer and we opened for Mountain in front of four or five thousand people, and that’s how my first full gig, fronting and singing for a band, came about!

It was a baptism of fire, but that sort of thing definitely makes you pull your finger out!

RM: There are many instances of stories told backstage stay backstage but the wonderful anecdotes I’ve heard from you in the past, and the one you’ve just told, leads to the obvious question:

Surely you should be writing a book?

JV: Yeah, I know, people say that to me all the time!

The problem is I don’t have a very good memory for tying all the things together.

When I read other people’s books – like Keith Richards' book – he remembers all this stuff about when he was a young kid, but I don’t remember anything! [laughs]

RM: While you might not be putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard, you still put fine voice to your songs.

You are still in great form vocally with a very strong, clean upper register – I’m presuming you look after the voice or exercise the vocal chords routinely?

JV: I sing every day. Because of where we are, we don’t really have any neighbours, so I can sing properly and practice at, basically, stage volume.

In fact I can really go for it! [laughs].

And because it’s a muscle, there’s no point in pussyfooting around with it – you have to work it.

RM: You've always been very off-handed about your guitar playing, that you "just play and see what comes out" to paraphrase your good self, but you have a very natural feel on the instrument, which is primarily your Fret King Black Label Corona signature guitar.

You can give it the full Hendrix when required but you’re an expressive and melodic player; one who knows the space between the notes is as important as the notes themselves – all of which is showcased to fine effect on latest album, Passion.

JV: Well first of all, thank you very much. I must admit the whole shredding thing, that’s happening again, does my head in; I just can’t listen to it! [laughs]

I know artists are always going to say their latest album is their best album but I do honestly believe Passion is my best album – which is great considering it’s also the one that celebrates the fifty years.

I’m very pleased with Passion.

RM: It’s also a musical autobiography; each song tells a tale about you, your influences, or lyrically emphasises something you are passionate about.

That autobiographical slant is there from the get-go on opening number Higher; lyrically it tells the tale of a young boy dreaming of guitars and rock 'n' roll success…

JV: That’s it exactly; it is me looking in the window at that guitar – I’m really glad you get that because that’s the story I was trying to get across on that song.

RM: It’s also interesting that Wise Up, one of the weightier songs on Passion, became so lyrically accurate and poignant, from a political and social unrest point of view, within weeks of the album being released.

JV: Well, I have to admit, while it’s partly accidental in its timing, I did kind of see the writing on the wall…

RM: I also want to give a nod to rock and roll number Bad Boy, which could only be about Chuck Berry.

Clearly he was a huge influence.

JV: Oh, absolutely. We – and by we I mean all rock musicians – owe a massive debt to Chuck Berry.

I don’t know if you spotted it but the last verse of Bad Boy is just a lift of Chuck Berry songs; that’s all it is!

And the funny thing about that is none of us ever played that stuff properly; we all got it wrong!

None of us played those riffs the right way but those approximations ended up being what rock music is, now. You must have seen the Chuck Berry documentary film, with Keith Richards in it?

RM: Hail! Hail! Rock ‘N’ Roll, yes…

JV: That little scene where Chuck is having a go at Keith when they’re doing Oh Carol and Chuck keeps telling him he’s playing it wrong – he is playing it wrong because we all played it wrong!

But we were so keen to play those songs that we all nearly learned them, then just cracked on! [laughs]

All the little nuances we just didn’t bother with, but all those little approximations have, as I just mentioned, turned in to what we do in rock and roll now. We owe Chuck Berry a lot.

RM: A genuine rock and roll pioneer. There’s another guitar great that needs honourable mention and that’s through the lovely little instrumental Open Road, which closes out Passion.

That piece highlights your tone and feel on guitar but there’s also a little nod to a gentlemen by the name of Hank B Marvin….

JV: There is, yes! He was a massive influence on me and I met him a couple of times; a lovely guy.

In fact the second time I met him he knew me straight way, which I thought was ridiculous – he came up and said "Hiya John!" and I thought "he knows me; he’s remembered me!" I could not believe it.

As for my playing, most of my guitar parts are busked – by that I mean I don’t work anything out when I’m recording; I just play. I get the backing track right and then just play over it or jam along with it, until I like what I’ve got.

The little Hank Marvin bit wasn’t planned; I just played it – but when I listened back to it I thought "that really works, that’s great." It honestly wasn’t scripted or anything like that.

RM: That unscripted approach goes back to what I said about your natural feel and expressiveness on a guitar – never the same solo twice, another of your strengths.

For me there’s nothing worse than a guitarist who has clearly rehearsed every bar of soloing – same solo every show syndrome.

JV: I can see why some guitarists would do that but, if you do, then you must get sick of the songs at some point. I never get tired of any of the songs we play because I never play them the same way twice.

RM: Which almost answers the final question before I’ve asked it... Fifty years on, John, is that Passion still there?

JV: Yeah, of course it is! This whole no gigs lockdown situation we’re in at the moment is killing me – we have a live streaming gig coming up later in September but I can’t wait at to get back out there and promote Passion!

RM: Well meanwhile, in your downtime, get that book written! [laughter].

More seriously, I look forward to seeing you back out on that road as soon as it’s safe to do so, John.

Thanks for your extended time with FabricationsHQ.

JV: It’s been a pleasure; thank you so much, Ross. Cheers!

Muirsical Conversation with John Verity

September 2020

Passion is available both on CD and digitally through

all the usual retailers.

Limited Edition Vinyl copies of Passion are available

via the official John Verity website.

http://www.johnverity.com/merchandise

You can also sign up to become a patron of JV Backstage Pass, which offers different levels of exclusive JV materials and discounts: http://www.johnverity.com/login

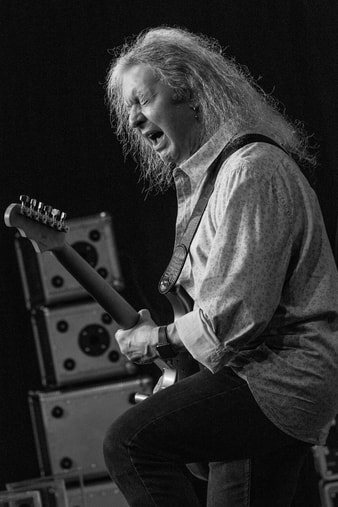

Photo Credits:

Phil Lightwood-Jones (top image)

Haluk Gurer (middle image)

Roy Cano (lower image)

Clearly he was a huge influence.

JV: Oh, absolutely. We – and by we I mean all rock musicians – owe a massive debt to Chuck Berry.

I don’t know if you spotted it but the last verse of Bad Boy is just a lift of Chuck Berry songs; that’s all it is!

And the funny thing about that is none of us ever played that stuff properly; we all got it wrong!

None of us played those riffs the right way but those approximations ended up being what rock music is, now. You must have seen the Chuck Berry documentary film, with Keith Richards in it?

RM: Hail! Hail! Rock ‘N’ Roll, yes…

JV: That little scene where Chuck is having a go at Keith when they’re doing Oh Carol and Chuck keeps telling him he’s playing it wrong – he is playing it wrong because we all played it wrong!

But we were so keen to play those songs that we all nearly learned them, then just cracked on! [laughs]

All the little nuances we just didn’t bother with, but all those little approximations have, as I just mentioned, turned in to what we do in rock and roll now. We owe Chuck Berry a lot.

RM: A genuine rock and roll pioneer. There’s another guitar great that needs honourable mention and that’s through the lovely little instrumental Open Road, which closes out Passion.

That piece highlights your tone and feel on guitar but there’s also a little nod to a gentlemen by the name of Hank B Marvin….

JV: There is, yes! He was a massive influence on me and I met him a couple of times; a lovely guy.

In fact the second time I met him he knew me straight way, which I thought was ridiculous – he came up and said "Hiya John!" and I thought "he knows me; he’s remembered me!" I could not believe it.

As for my playing, most of my guitar parts are busked – by that I mean I don’t work anything out when I’m recording; I just play. I get the backing track right and then just play over it or jam along with it, until I like what I’ve got.

The little Hank Marvin bit wasn’t planned; I just played it – but when I listened back to it I thought "that really works, that’s great." It honestly wasn’t scripted or anything like that.

RM: That unscripted approach goes back to what I said about your natural feel and expressiveness on a guitar – never the same solo twice, another of your strengths.

For me there’s nothing worse than a guitarist who has clearly rehearsed every bar of soloing – same solo every show syndrome.

JV: I can see why some guitarists would do that but, if you do, then you must get sick of the songs at some point. I never get tired of any of the songs we play because I never play them the same way twice.

RM: Which almost answers the final question before I’ve asked it... Fifty years on, John, is that Passion still there?

JV: Yeah, of course it is! This whole no gigs lockdown situation we’re in at the moment is killing me – we have a live streaming gig coming up later in September but I can’t wait at to get back out there and promote Passion!

RM: Well meanwhile, in your downtime, get that book written! [laughter].

More seriously, I look forward to seeing you back out on that road as soon as it’s safe to do so, John.

Thanks for your extended time with FabricationsHQ.

JV: It’s been a pleasure; thank you so much, Ross. Cheers!

Muirsical Conversation with John Verity

September 2020

Passion is available both on CD and digitally through

all the usual retailers.

Limited Edition Vinyl copies of Passion are available

via the official John Verity website.

http://www.johnverity.com/merchandise

You can also sign up to become a patron of JV Backstage Pass, which offers different levels of exclusive JV materials and discounts: http://www.johnverity.com/login

Photo Credits:

Phil Lightwood-Jones (top image)

Haluk Gurer (middle image)

Roy Cano (lower image)