Come and see the show...

Muirsical Conversation with Greg Lake

Greg Lake was a founder member of King Crimson and an integral component of the band’s ground-breaking debut album In the Court of the Crimson King.

However the singer and musician will always be best known as one third of Emerson Lake & Palmer, arguably the biggest super-group of all time and a band responsible for some forty million record sales.

The music they created in the early 70s was a a fusion of progressive rock, classical and European influences – making ELP one of the most musically adventurous rock bands ever to perform and record.

ELP were one of the world’s biggest bands in the 70s and their 90s reunion produced two studio albums and further world tours.

Between those two decades Lake formed the Greg Lake Band (which included Gary Moore) and released two excellent solo albums: Greg Lake (1981) and Manoeuvres (1983).

Lake also performed with Asia (temporarily replacing John Wetton) in 1983 and then reunited with Keith Emerson to form the power-prog trio Emerson Lake & Powell, releasing one album in 1986.

Millennium highlights included a new Greg Lake Band touring the UK in 2005, a North American tour with Keith Emerson in 2010 and the Emerson Lake & Palmer 40th Anniversary reunion concert that same year.

That's quite the musical resumé but some of Greg Lake’s most satisfying moments as a performer have come in what is now his sixth performing and recording decade, courtesy of his one-man show Songs of a Lifetime.

FabricationsHQ caught up with Greg Lake shortly before his Songs of a Lifetime UK tour to talk about those one-man shows, King Crimson and the platinum highs & Love Beach lows of ELP.

And also discovered that one of rock’s true greats has a musical fondness for Scotland – and its national dish…

Ross Muir: Hi Greg, thanks for sitting in for a chat with FabricationsHQ.

Greg Lake: Hello! How are you?

RM: I’m fine, thank you for asking, but more importantly how are you?

We were originally going to have a chat about a week ago but you weren’t feeling too good and had to call off…

GL: I did. I had the flu and it was horrible!

RM: Oh, not nice.

GL: No, it isn’t nice and it went on for two weeks as well. It was a really nasty bug. But it was quite amazing – the morning I got the flu I got a note through the door from my doctor saying it’s time to have your flu jab (laughs). The very day I got it!

RM: We would call that "Lucky White Heather" [laughs]. We’ve got those letters coming through household letterboxes right now…

GL: I’ll tell you what, do yourself a favour; I always used to say "Oh bollocks" [laughter] and, you know, didn’t bother. But I’ve got to tell you, for that one little moment of a jab it’s worth having, rather than going through two weeks of that misery. You think it’s going to go away in a few days – but it doesn’t!

RM: No, the bugger tends to hang about. But that leads to one of the main reasons for this chat and the upcoming UK tour. I assume you are going to be okay vocally, come tour time?

GL: Oh yeah, I’m fine now. It was a rather nasty bug – but once it goes it goes!

RM: Good to hear. Now, the Songs of a Lifetime tour includes a couple of dates in Scotland, which is great because it’s not every artist – well, to be more accurate, booking agent – that schedules dates up here.

So thanks for coming up this way.

GL: Oh don’t be silly and, funnily enough, ever since the very early days of ELP we always used to book a tour that included Scotland at Christmas. We always used to love it because the atmosphere up there, right over that winter period and through New Year, is really magical. And it was just one of those things we used to love doing. And we played, I remember, at Greens… was it Green’s Playhouse?

RM: It was Green’s Playhouse, yes. Became the Glasgow Apollo in 1973.

GL: Yeah, "It’s good, it’s Greens!" That’s what they used to say. I always remember that and the green carpet [laughs]. The audiences were fantastic, absolutely electrifying.

So one of the highlights of a British tour was going up to Scotland. And of course we would always buy a little whisky to bring home, you know? [laughs].

And just as luck would have it I have to like haggis! I’m one of the few people who can’t understand why people don’t like it – I think it’s fantastic!

RM: Good man, that’s great to hear. Have you tried vegetarian haggis by any chance?

And yes, there is such a thing…

GL: No, I never have! [laughs] But I do have haggis regularly at home, with the neeps and tatties!

RM: Clearly there must be Scottish genes in there somewhere…

GL: There must be I think, yes!

RM: So, live music, Christmas, Hogmanay and a nice single malt…

GL: You can’t go far wrong, can you? But it’s a happy thing for me every time I go to Scotland, it’s always been somewhere I’ve felt welcome.

And the music of course… Scotland is a very musical place. Just look at the musicians, the singers and the performers that have come out of Scotland.

RM: I think we do punch above our weight as regards population size against the nation’s musicality.

And across all the genres, not just traditional or folk-based. We do seem to have a great line of music that goes back generations, long may that continue.

GL: It is a fantastic place for music and I think that’s one of the reasons why ELP took off there in the very early days. They’re very quick, people in Scotland, to pick up on good music – they’re very alert to good music.

RM: I think that’s right but also – and this was true of Green’s Playhouse and Glasgow Empire audiences – they don’t suffer fools gladly. If an act wasn’t any good they would let you know pretty quickly…

GL: That is very true! [laughs].

RM: Some of the biggest names in variety entertainment learned that at The Empire. Morecambe and Wise, Des O’Connor and many others; they all suffered a baptism of fire.

GL: You’re either in or you’re out. And you don’t want to be out!

RM: I’d like to feature a few songs through our conversation and, fittingly, we start with the perfect song for those who dared to take on Glasgow audiences back in the day...

However the singer and musician will always be best known as one third of Emerson Lake & Palmer, arguably the biggest super-group of all time and a band responsible for some forty million record sales.

The music they created in the early 70s was a a fusion of progressive rock, classical and European influences – making ELP one of the most musically adventurous rock bands ever to perform and record.

ELP were one of the world’s biggest bands in the 70s and their 90s reunion produced two studio albums and further world tours.

Between those two decades Lake formed the Greg Lake Band (which included Gary Moore) and released two excellent solo albums: Greg Lake (1981) and Manoeuvres (1983).

Lake also performed with Asia (temporarily replacing John Wetton) in 1983 and then reunited with Keith Emerson to form the power-prog trio Emerson Lake & Powell, releasing one album in 1986.

Millennium highlights included a new Greg Lake Band touring the UK in 2005, a North American tour with Keith Emerson in 2010 and the Emerson Lake & Palmer 40th Anniversary reunion concert that same year.

That's quite the musical resumé but some of Greg Lake’s most satisfying moments as a performer have come in what is now his sixth performing and recording decade, courtesy of his one-man show Songs of a Lifetime.

FabricationsHQ caught up with Greg Lake shortly before his Songs of a Lifetime UK tour to talk about those one-man shows, King Crimson and the platinum highs & Love Beach lows of ELP.

And also discovered that one of rock’s true greats has a musical fondness for Scotland – and its national dish…

Ross Muir: Hi Greg, thanks for sitting in for a chat with FabricationsHQ.

Greg Lake: Hello! How are you?

RM: I’m fine, thank you for asking, but more importantly how are you?

We were originally going to have a chat about a week ago but you weren’t feeling too good and had to call off…

GL: I did. I had the flu and it was horrible!

RM: Oh, not nice.

GL: No, it isn’t nice and it went on for two weeks as well. It was a really nasty bug. But it was quite amazing – the morning I got the flu I got a note through the door from my doctor saying it’s time to have your flu jab (laughs). The very day I got it!

RM: We would call that "Lucky White Heather" [laughs]. We’ve got those letters coming through household letterboxes right now…

GL: I’ll tell you what, do yourself a favour; I always used to say "Oh bollocks" [laughter] and, you know, didn’t bother. But I’ve got to tell you, for that one little moment of a jab it’s worth having, rather than going through two weeks of that misery. You think it’s going to go away in a few days – but it doesn’t!

RM: No, the bugger tends to hang about. But that leads to one of the main reasons for this chat and the upcoming UK tour. I assume you are going to be okay vocally, come tour time?

GL: Oh yeah, I’m fine now. It was a rather nasty bug – but once it goes it goes!

RM: Good to hear. Now, the Songs of a Lifetime tour includes a couple of dates in Scotland, which is great because it’s not every artist – well, to be more accurate, booking agent – that schedules dates up here.

So thanks for coming up this way.

GL: Oh don’t be silly and, funnily enough, ever since the very early days of ELP we always used to book a tour that included Scotland at Christmas. We always used to love it because the atmosphere up there, right over that winter period and through New Year, is really magical. And it was just one of those things we used to love doing. And we played, I remember, at Greens… was it Green’s Playhouse?

RM: It was Green’s Playhouse, yes. Became the Glasgow Apollo in 1973.

GL: Yeah, "It’s good, it’s Greens!" That’s what they used to say. I always remember that and the green carpet [laughs]. The audiences were fantastic, absolutely electrifying.

So one of the highlights of a British tour was going up to Scotland. And of course we would always buy a little whisky to bring home, you know? [laughs].

And just as luck would have it I have to like haggis! I’m one of the few people who can’t understand why people don’t like it – I think it’s fantastic!

RM: Good man, that’s great to hear. Have you tried vegetarian haggis by any chance?

And yes, there is such a thing…

GL: No, I never have! [laughs] But I do have haggis regularly at home, with the neeps and tatties!

RM: Clearly there must be Scottish genes in there somewhere…

GL: There must be I think, yes!

RM: So, live music, Christmas, Hogmanay and a nice single malt…

GL: You can’t go far wrong, can you? But it’s a happy thing for me every time I go to Scotland, it’s always been somewhere I’ve felt welcome.

And the music of course… Scotland is a very musical place. Just look at the musicians, the singers and the performers that have come out of Scotland.

RM: I think we do punch above our weight as regards population size against the nation’s musicality.

And across all the genres, not just traditional or folk-based. We do seem to have a great line of music that goes back generations, long may that continue.

GL: It is a fantastic place for music and I think that’s one of the reasons why ELP took off there in the very early days. They’re very quick, people in Scotland, to pick up on good music – they’re very alert to good music.

RM: I think that’s right but also – and this was true of Green’s Playhouse and Glasgow Empire audiences – they don’t suffer fools gladly. If an act wasn’t any good they would let you know pretty quickly…

GL: That is very true! [laughs].

RM: Some of the biggest names in variety entertainment learned that at The Empire. Morecambe and Wise, Des O’Connor and many others; they all suffered a baptism of fire.

GL: You’re either in or you’re out. And you don’t want to be out!

RM: I’d like to feature a few songs through our conversation and, fittingly, we start with the perfect song for those who dared to take on Glasgow audiences back in the day...

RM: The Songs of a Lifetime show is an interesting concept – part one-man performance, part audio-biography. Can you tell me more about the format and how the idea came about?

GL: Well, the way it came about was I writing – and have just finished – my autobiography called, unsurprisingly, Lucky Man. And from time to time, as I was writing it, songs would pop up that were pivotal to my career in some way.

Or influential. So I had this collection of songs and I realised that what they represented was this journey I’ve shared with the audiences over the years.

And every song, for me, has got a story attached to it but those songs, for the audiences, have got stories attached to them as well.

They’re not only my songs – there are songs by other artists – but they all kind of form this thread of continuity in my career. And so what I thought would be a good idea would be to do a little intimate concert where we shared these songs and we shared the memories or stories that each of us had about those songs.

I tell my stories, but I also let the audiences tell their stories. So if someone has got a particular story about experiencing that song in some context then I let them stand up with a microphone, they tell this story, I play the song.

Now, in that regard, it’s a kind of nostalgic storyteller thing. But, some time ago in London I went to see a man called Peter Ustinov, I’m sure you know of him…

RM: Oh absolutely. He was a wonderful raconteur…

GL: He did a one-man show and I couldn’t believe it. It was just fantastic and it went by as if it were five minutes when really it was two hours.

He was so good, so spellbinding, that the time just flew by. And I really admired him because I thought Christ, what an amazing thing to be able to entertain an audience for two hours, on your own.

So I always had this thing in the back of my mind, like a challenge – could I do that? Would I be good enough to do that?

So when I set out to do this show I decided I didn’t want it to be one of those storyteller legend in his own lunchtime things (laughter); sitting on a stool, strumming a guitar… no, that’s boring. So I decided to make a one-man show that was dynamic, dramatic and intense, emotionally. And funny and entertaining.

GL: Well, the way it came about was I writing – and have just finished – my autobiography called, unsurprisingly, Lucky Man. And from time to time, as I was writing it, songs would pop up that were pivotal to my career in some way.

Or influential. So I had this collection of songs and I realised that what they represented was this journey I’ve shared with the audiences over the years.

And every song, for me, has got a story attached to it but those songs, for the audiences, have got stories attached to them as well.

They’re not only my songs – there are songs by other artists – but they all kind of form this thread of continuity in my career. And so what I thought would be a good idea would be to do a little intimate concert where we shared these songs and we shared the memories or stories that each of us had about those songs.

I tell my stories, but I also let the audiences tell their stories. So if someone has got a particular story about experiencing that song in some context then I let them stand up with a microphone, they tell this story, I play the song.

Now, in that regard, it’s a kind of nostalgic storyteller thing. But, some time ago in London I went to see a man called Peter Ustinov, I’m sure you know of him…

RM: Oh absolutely. He was a wonderful raconteur…

GL: He did a one-man show and I couldn’t believe it. It was just fantastic and it went by as if it were five minutes when really it was two hours.

He was so good, so spellbinding, that the time just flew by. And I really admired him because I thought Christ, what an amazing thing to be able to entertain an audience for two hours, on your own.

So I always had this thing in the back of my mind, like a challenge – could I do that? Would I be good enough to do that?

So when I set out to do this show I decided I didn’t want it to be one of those storyteller legend in his own lunchtime things (laughter); sitting on a stool, strumming a guitar… no, that’s boring. So I decided to make a one-man show that was dynamic, dramatic and intense, emotionally. And funny and entertaining.

Songs of a Lifetime – part one-man show, part audio-biography. Volume 1 of Lucky Man,

Greg Lake's autobiography, has been made available as an audiobook with the final two

volumes to follow on at later date/s.

GL: I spent a year perfecting the show and I took it out around America and Canada. And it was fantastic.

It really was great; people loved it. They got it, they got into it, they understood what it was and every night was a standing ovation. It was just a joy to do and a pleasure for me to do.

But before I left to go on the tour of the United States – the day before I left – I sat in my living room and thought "Oh God what have I done!" Because, if it doesn’t work, you’re the only person on that stage and that’s a terrible thing. So for a moment I had this flash of self-doubt because you never know.

But I went on the stage, did the show and it was the most fantastic feeling.

I’ll tell you what it was like – if you’ve been away for a long time and you come back home and your family gets together with all the people up the street and they have a party for you when you come in [laughs]… that’s what it’s like!

There’s this feeling of bonding and everyone belonging together, because they are all from this generation, that I share, of shared music.

We all shared music together in the sense, that, if you went to buy an album you’d bring it home, sit down with your friends and play the record and share the album sleeve; everyone would share that experience.

Then, at some point, I don’t know when exactly it was – around ’75, ’76? – they invented the Sony Walkman.

RM: It was right at the end of the 70s, was the in-thing by the start of the 80s…

GL: ...and music became a solitary experience. You put on the headphones, you’d listen to the music but you’d listen to it alone. And then what used to be the album became the CD and it all shrunk in size and now, of course, it’s just a download!

But I’m a child of that shared music and for me there’s a value in that; there’s a bonding in that. And that’s what brought all those people to the festivals, these great festivals, which I was lucky and privileged enough to be a part of.

We did the Isle of Wight Festival; we did California Jam where there was more than three hundred thousand people. And they didn’t come just to see Emerson Lake and Palmer; they came to share in the event.

And what this tour, Songs of a Lifetime does, it enables people to re-share that sense of belonging to one identity as if you were in your teens and you had your mates and you were just sharing in this music.

That’s the feeling people get when they come to see the show.

RM: You’ve created a musical camaraderie. And you’re right about losing that shared experience.

I understand the appeal and instant availability of the Internet – most of the music I purchase, listen to or receive for review is via download – but there was something about that whole touchy-feely, record sleeve and vinyl era, getting together to listen to something.

We have lost that to a large extent and I’m not sure we’ll ever get it back.

GL: And the music of course was great in that era and it was a very effervescent time, creatively.

But what I think was important about it was people identified with it the music. You would get together with a group of friends who were like-minded, who liked the same things you did.

And so you have a whole group of people who would be into Pink Floyd or ELP or Jimi Hendrix.

They would all get together and there would be a sense of belonging, a sense of identity.

And in that way it was almost a club atmosphere, there was a sense of gathering about it. And I found a tremendous value in that and a tremendous atmosphere whenever you played a show.

I talked a little earlier about ELP coming to Glasgow for the first time. It was incredible, that sense of camaraderie and togetherness in that room and it’s something I will always treasure.

In a way, with these concerts that I’m doing, I do that same thing in the room. If you come to a show you’ll see what I mean. There is this sense of being together and of knowing why you are there.

And a lot of people will tell their story; it starts slowly because people are shy but the moment one person stands up, the second one stands up and before you know it you’ve got everyone in the room telling stories.

RM: Fabulous…

GL: And some of those stories are absolutely electrifying. Some of course are very tragic or sad, but some of them are very happy and funny. It’s like a roller-coaster or emotion. And the music too is very colourful – it’s not all my songs, it’s not all ELP and King Crimson. I do songs by other artists that influenced me throughout my career. So the show is very varied and there will be some surprises for people, songs they really wouldn’t have expected to hear.

RM: And you have also created your own musical accompaniments and backing tracks?

GL: Yes, all the recordings I’ve done are especially for the show. And they’re not just guitar recordings, some are orchestral and each is different. I made them that way so it doesn’t get boring and is entertaining.

RM: Sounds like a perfect format. I hope to be at the Glasgow gig and if I do I’ll catch up with you and buy you that single malt mentioned earlier…

GL: Oh please do come back and say hello and I’m sure you would enjoy it.

Even people who are not into ELP and King Crimson, they enjoy it too, because you’ll hear things like an Elvis Presley song being done, it’s not just prog-rock.

It’s a trip through the music of the late twentieth century, in a way.

RM: Yes, and people tend to forget that beyond the last forty years, King Crimson and ELP, your own musical upbringing would have included Elvis Presley, The Beatles…

GL: Yes, of course!

RM: So going back that distance, how and when does a young Greg Lake pick up a guitar and get into music?

GL: Well, it happened to me when I was twelve years old. I was round at my friend’s house and he had a broken guitar; it only had one string on it!

But luckily enough it was the sixth string, the big lower E string, and I started to pick out the tune Peter Gunn (as recorded) by Duane Eddy. I’m sure you know the one – (sings) "Bam-bam Bam-bam Bam-bam Bam-bam!

So I started to play the tune and I could just about do it on this one string and it gave me the idea "I wonder if I could actually learn to play the guitar?"

We were quite a poor family so I never expected to get a guitar but I said to my mum "is there any chance I could have a guitar for Christmas?" She said "No" and that was the end of it [laughs].

But, sure enough, when Christmas came there it was and I had a guitar.

So I started playing, went for lessons and that was how it started, really.

RM: Interesting you mentioned the Peter Gunn theme – is that why Peter Gunn made an appearance on ELP’s Works tour in 1977?

GL: It was one of the reasons but to be honest with you I can’t remember why we picked up on it.

It probably was me who started playing it and then Keith would have jumped in. That’s probably how it started.

RM: I was just curious because it was such a great, punchy opening to those particular sets…

GL: It is a great opening track, one of the great rock and roll openers.

In the early days, 1965, ’66. ’67, the local bands, the way they would come on would be to use something like that, in their sparkle glitter jackets!

RM: Now, from guitar to bass. It’s maybe unfair to say it’s an unusual switch but, generally, budding pop or rock stars would want to be in front of the microphone or playing lead guitar.

What caused you to pick up the four-string?

GL: As well as playing guitar I was a lead singer; I had got into singing.

But what happened was Robert Fripp and I had gone to the same guitar teacher, a man called Don Strike.

We also practiced together, round at each other’s houses; so Robert and I were like a mirror-copy of each other as guitar players and when we came to form King Crimson we wanted to keep the band as a four-piece.

Robert said to me "Look, you’re really the lead singer, so instead of us getting a separate bass player would you consider playing bass and I can play lead guitar."

Then all we needed was someone who could play drums and somebody else on keyboards, or a multi-instrumentalist. That’s how it started; I only really started playing bass then.

RM: So it was almost just a requirement to fit the form of the band?

GL: It really was. It was just a convenience and I thought to myself "six-strings, four-strings, how hard can it be?" [laughter]. I didn’t intend doing it for very long.

And also, I have to say, when I started playing bass I thought it was just a question of playing bigger strings and less notes [laughs]. But I very quickly learned that playing bass is an art-form in and of itself.

It’s not something that you can just pick up and do, you have to think about it and you have to work at it.

So it was a bit of a shock – I had to get in there and I had to learn how to play the bass guitar.

RM: Well fair to say it really worked out for you as did that King Crimson debut. People will associate you first and foremost with ELP but In the Court of the Crimson King is a genuinely ground-breaking and innovative album.

Greg Lake's autobiography, has been made available as an audiobook with the final two

volumes to follow on at later date/s.

GL: I spent a year perfecting the show and I took it out around America and Canada. And it was fantastic.

It really was great; people loved it. They got it, they got into it, they understood what it was and every night was a standing ovation. It was just a joy to do and a pleasure for me to do.

But before I left to go on the tour of the United States – the day before I left – I sat in my living room and thought "Oh God what have I done!" Because, if it doesn’t work, you’re the only person on that stage and that’s a terrible thing. So for a moment I had this flash of self-doubt because you never know.

But I went on the stage, did the show and it was the most fantastic feeling.

I’ll tell you what it was like – if you’ve been away for a long time and you come back home and your family gets together with all the people up the street and they have a party for you when you come in [laughs]… that’s what it’s like!

There’s this feeling of bonding and everyone belonging together, because they are all from this generation, that I share, of shared music.

We all shared music together in the sense, that, if you went to buy an album you’d bring it home, sit down with your friends and play the record and share the album sleeve; everyone would share that experience.

Then, at some point, I don’t know when exactly it was – around ’75, ’76? – they invented the Sony Walkman.

RM: It was right at the end of the 70s, was the in-thing by the start of the 80s…

GL: ...and music became a solitary experience. You put on the headphones, you’d listen to the music but you’d listen to it alone. And then what used to be the album became the CD and it all shrunk in size and now, of course, it’s just a download!

But I’m a child of that shared music and for me there’s a value in that; there’s a bonding in that. And that’s what brought all those people to the festivals, these great festivals, which I was lucky and privileged enough to be a part of.

We did the Isle of Wight Festival; we did California Jam where there was more than three hundred thousand people. And they didn’t come just to see Emerson Lake and Palmer; they came to share in the event.

And what this tour, Songs of a Lifetime does, it enables people to re-share that sense of belonging to one identity as if you were in your teens and you had your mates and you were just sharing in this music.

That’s the feeling people get when they come to see the show.

RM: You’ve created a musical camaraderie. And you’re right about losing that shared experience.

I understand the appeal and instant availability of the Internet – most of the music I purchase, listen to or receive for review is via download – but there was something about that whole touchy-feely, record sleeve and vinyl era, getting together to listen to something.

We have lost that to a large extent and I’m not sure we’ll ever get it back.

GL: And the music of course was great in that era and it was a very effervescent time, creatively.

But what I think was important about it was people identified with it the music. You would get together with a group of friends who were like-minded, who liked the same things you did.

And so you have a whole group of people who would be into Pink Floyd or ELP or Jimi Hendrix.

They would all get together and there would be a sense of belonging, a sense of identity.

And in that way it was almost a club atmosphere, there was a sense of gathering about it. And I found a tremendous value in that and a tremendous atmosphere whenever you played a show.

I talked a little earlier about ELP coming to Glasgow for the first time. It was incredible, that sense of camaraderie and togetherness in that room and it’s something I will always treasure.

In a way, with these concerts that I’m doing, I do that same thing in the room. If you come to a show you’ll see what I mean. There is this sense of being together and of knowing why you are there.

And a lot of people will tell their story; it starts slowly because people are shy but the moment one person stands up, the second one stands up and before you know it you’ve got everyone in the room telling stories.

RM: Fabulous…

GL: And some of those stories are absolutely electrifying. Some of course are very tragic or sad, but some of them are very happy and funny. It’s like a roller-coaster or emotion. And the music too is very colourful – it’s not all my songs, it’s not all ELP and King Crimson. I do songs by other artists that influenced me throughout my career. So the show is very varied and there will be some surprises for people, songs they really wouldn’t have expected to hear.

RM: And you have also created your own musical accompaniments and backing tracks?

GL: Yes, all the recordings I’ve done are especially for the show. And they’re not just guitar recordings, some are orchestral and each is different. I made them that way so it doesn’t get boring and is entertaining.

RM: Sounds like a perfect format. I hope to be at the Glasgow gig and if I do I’ll catch up with you and buy you that single malt mentioned earlier…

GL: Oh please do come back and say hello and I’m sure you would enjoy it.

Even people who are not into ELP and King Crimson, they enjoy it too, because you’ll hear things like an Elvis Presley song being done, it’s not just prog-rock.

It’s a trip through the music of the late twentieth century, in a way.

RM: Yes, and people tend to forget that beyond the last forty years, King Crimson and ELP, your own musical upbringing would have included Elvis Presley, The Beatles…

GL: Yes, of course!

RM: So going back that distance, how and when does a young Greg Lake pick up a guitar and get into music?

GL: Well, it happened to me when I was twelve years old. I was round at my friend’s house and he had a broken guitar; it only had one string on it!

But luckily enough it was the sixth string, the big lower E string, and I started to pick out the tune Peter Gunn (as recorded) by Duane Eddy. I’m sure you know the one – (sings) "Bam-bam Bam-bam Bam-bam Bam-bam!

So I started to play the tune and I could just about do it on this one string and it gave me the idea "I wonder if I could actually learn to play the guitar?"

We were quite a poor family so I never expected to get a guitar but I said to my mum "is there any chance I could have a guitar for Christmas?" She said "No" and that was the end of it [laughs].

But, sure enough, when Christmas came there it was and I had a guitar.

So I started playing, went for lessons and that was how it started, really.

RM: Interesting you mentioned the Peter Gunn theme – is that why Peter Gunn made an appearance on ELP’s Works tour in 1977?

GL: It was one of the reasons but to be honest with you I can’t remember why we picked up on it.

It probably was me who started playing it and then Keith would have jumped in. That’s probably how it started.

RM: I was just curious because it was such a great, punchy opening to those particular sets…

GL: It is a great opening track, one of the great rock and roll openers.

In the early days, 1965, ’66. ’67, the local bands, the way they would come on would be to use something like that, in their sparkle glitter jackets!

RM: Now, from guitar to bass. It’s maybe unfair to say it’s an unusual switch but, generally, budding pop or rock stars would want to be in front of the microphone or playing lead guitar.

What caused you to pick up the four-string?

GL: As well as playing guitar I was a lead singer; I had got into singing.

But what happened was Robert Fripp and I had gone to the same guitar teacher, a man called Don Strike.

We also practiced together, round at each other’s houses; so Robert and I were like a mirror-copy of each other as guitar players and when we came to form King Crimson we wanted to keep the band as a four-piece.

Robert said to me "Look, you’re really the lead singer, so instead of us getting a separate bass player would you consider playing bass and I can play lead guitar."

Then all we needed was someone who could play drums and somebody else on keyboards, or a multi-instrumentalist. That’s how it started; I only really started playing bass then.

RM: So it was almost just a requirement to fit the form of the band?

GL: It really was. It was just a convenience and I thought to myself "six-strings, four-strings, how hard can it be?" [laughter]. I didn’t intend doing it for very long.

And also, I have to say, when I started playing bass I thought it was just a question of playing bigger strings and less notes [laughs]. But I very quickly learned that playing bass is an art-form in and of itself.

It’s not something that you can just pick up and do, you have to think about it and you have to work at it.

So it was a bit of a shock – I had to get in there and I had to learn how to play the bass guitar.

RM: Well fair to say it really worked out for you as did that King Crimson debut. People will associate you first and foremost with ELP but In the Court of the Crimson King is a genuinely ground-breaking and innovative album.

RM: You also put your vocals to the band’s second album, In the Wake of Poseidon.

But by that time the band had fragmented and you had already been talking to Keith Emerson…

GL: Well, what happened was King Crimson were on tour in America, supporting the first album and we’d reached the end of the tour; we were actually in San Francisco at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West.

And two of the members of King Crimson, Ian MacDonald and Mike Giles, I think basically didn’t enjoy touring very much. They wanted to make studio albums.

So they decided they would stop touring and make studio records, which really left just Robert and I.

Robert wanted to keep the name and carry on with the band but I just didn’t feel the same way.

Had it been only one person leaving the band it may have been okay to replace them and carry on, but for half the band to go – and Ian MacDonald wrote a lot of material on that first record – I just didn’t feel it was honest to keep the name and just pretend nothing had happened.

So I said to Robert "It would have to be a new name and we’d have to form a completely new band" but Robert didn’t want to do that; he wanted to continue on with the name.

So I said "Well you carry on with it and the best of luck to you but I think I’ve got to go and do something else."

Now just by coincidence, that night at the same concert and on the same bill were The Nice.

I met Keith Emerson in the hotel bar after the show and we just started chatting. He asked "How’s King Crimson going, I’ve heard you’re doing really well" and I said "Sadly, they’ve just broken up, Keith!"

Keith said "That’s incredible because I’m just finishing with The Nice. I can’t take The Nice a lot further and I’m thinking of moving on. I wonder if we could form a band together?"

That was such an interesting thought because Keith’s background was European influenced music, the same way King Crimson’s was European influenced.

And that almost defines progressive music – although I don’t like the term progressive music – but, anyway, Keith and I decided to form a band together and that was the beginning of ELP.

RM: It sounds like it was almost a case of musical fate…

GL: Honestly, it was an absolute coincidence! But yes I also appeared on the second King Crimson album simply because at that time Robert hadn’t really gotten anybody to replace me.

He wanted to get on with the record so I said "I don’t mind doing the vocals until you find someone."

So I did a couple of tracks on that record as well.

RM: Just as an aside, I’m sure you will have read or heard that Robert recently confirmed he is stepping away from music – primarily because of his disillusionment with the business aspect of the industry and the change in relationship between artist and label.

There have been massive changes in music over the decades and perhaps most significantly in recent times; can you understand Robert’s frustrations and see where he’s coming from?

GL: I don’t know. I think Robert’s had a very good run with the idea of King Crimson and maybe he’s reached a point where he’s had enough of it, you know?

If you’re in it just for the business then I can understand that it isn’t as great as it used to be, in many ways. But I’m not in it for the business, I’m in it for the music.

This is not a job to me so if it’s not work, why would I stop doing it?

If the business stops I’ll still play the music. I played the music before the business started [laughs] and I’ll be playing the music when the business stops for me.

The business, really, is a by-product of the music and it’s a fortunate one because I’m able to live from it and it’s able to pay for my life. And that’s a great thing.

But you’d have to ask Robert why he has had enough or why he wants to walk away; he’s made his contribution and if he feels the time has come for him to not do that then he’s probably wise to step out and not do it for a while. And maybe he’ll come back and maybe he won’t.

RM: Indeed; only musical time will tell if he does or not. I hope he does.

Moving on from Robert and King Crimson to Keith, Carl Palmer and ELP...

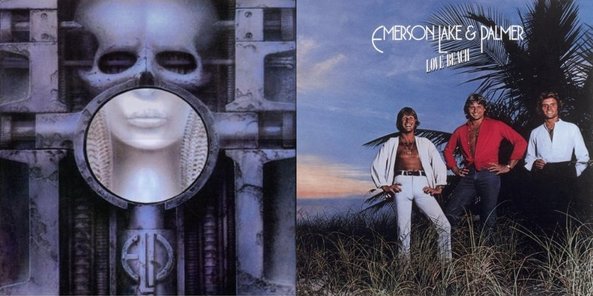

I have to start by telling you that a few years ago I drafted out my Top 20 list of all-time favourite albums and only one band appeared more than once – Emerson Lake and Palmer.

The specific albums were Brain Salad Surgery, one of ELP’s finest and most innovative records, and Works Volume 1. But I know you feel Works Volume 1 heralded in the beginning of the end for ELP and the start of the separation – no more than the sum of their parts as opposed to a cohesive trio…

GL: Yes.

RM: But each of you, individually, produced an excellent solo side of music before reconvening for a great ELP side. Works Volume 1 holds up extremely well…

GL: It does and it is a great record. I do believe it’s a great record.

But, the first five albums – Emerson Lake and Palmer, Tarkus, Pictures at an Exhibition, Trilogy and Brain Salad Surgery – all of those records had a unique and innovative power about them, creatively.

They were different. They really were the sound and the soul and the energy of Emerson Lake and Palmer.

There was no other thing like them. The band had a real sound to it and they were very powerful, very dynamic records.

In some ways they were often very beautiful records, like the track Trilogy for example or some of the ballads such as Still You Turn Me On, Lucky Man, or From the Beginning.

Then there's Karn Evil 9 and "Welcome back my friends…" These were really the creative highlights, for me anyway, of ELP.

When it came to Works Volume 1, although it was a great record it kind of was the beginning of the end. Instead of being Emerson Lake and Palmer and the sound of Emerson Lake and Palmer it was the sound of orchestras. Or ELP through the voice of an orchestra, to a large degree.

RM: That’s a fair point. I just happen to love that.

GL: But it was also each of us going off in our individual directions, so it was like a fragmented version of ELP. But I can look back at that album and think there were a lot of really, lovely tracks on there.

Pirates I like for example, very much.

RM: Well I hope we have time to elaborate because, funnily enough, if I’m discussing desert island tracks I have six, specific all-time favourite songs. And Pirates is one of those songs.

It's just such a majestic piece of work.

GL: Oh it’s just a lovely thing and it wasn’t one of those songs which, obviously, ever got a lot of radio play. But, if you get into it, it really is a little masterpiece.

It tells a story, it’s full of colourful pictures, the music’s dramatic… Leonard Bernstein liked it.

RM: I’m not surprised. When people talk to me about Pirates or I’m trying to put across why I feel it’s such an important composition I always say it’s the soundtrack to the greatest pirate film never made.

GL: It is, you’re absolutely right. In fact, funnily enough, somebody did an amateur collage of pirate images to match the music and it was really stunning.

But we couldn’t put it out, because it would require so much copyright clearance it wouldn’t make sense.

But it was the most brilliant thing, it really illustrated the visions of what the song says.

So, yeah, I love Pirates from that record; I also love Closer to Believing.

RM: Oh that’s a beautiful song. Funny you should mention that particular track as well, because it ties in to what you were saying earlier about different songs and how important they are to different people…

I’m a 70s rock boy at heart and in that decade would be listening to a lot of progressive music, some jazz-fusion and a lot of late 60s material.

My parents were very much into 50s music – swing, big band, the crooners – but when I played songs like Closer to Believing and C’est la Vie and they took to them immediately.

My mum loved Closer to Believing and my dad loved C’est la Vie so, again, we have songs crossing genres and generations.

GL: C’est la Vie is a nice song. I lived in Paris for a while and that’s one of the stories I tell on stage.

I do C’est la Vie in the show and I’ve always had a love for that French sound…

But by that time the band had fragmented and you had already been talking to Keith Emerson…

GL: Well, what happened was King Crimson were on tour in America, supporting the first album and we’d reached the end of the tour; we were actually in San Francisco at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West.

And two of the members of King Crimson, Ian MacDonald and Mike Giles, I think basically didn’t enjoy touring very much. They wanted to make studio albums.

So they decided they would stop touring and make studio records, which really left just Robert and I.

Robert wanted to keep the name and carry on with the band but I just didn’t feel the same way.

Had it been only one person leaving the band it may have been okay to replace them and carry on, but for half the band to go – and Ian MacDonald wrote a lot of material on that first record – I just didn’t feel it was honest to keep the name and just pretend nothing had happened.

So I said to Robert "It would have to be a new name and we’d have to form a completely new band" but Robert didn’t want to do that; he wanted to continue on with the name.

So I said "Well you carry on with it and the best of luck to you but I think I’ve got to go and do something else."

Now just by coincidence, that night at the same concert and on the same bill were The Nice.

I met Keith Emerson in the hotel bar after the show and we just started chatting. He asked "How’s King Crimson going, I’ve heard you’re doing really well" and I said "Sadly, they’ve just broken up, Keith!"

Keith said "That’s incredible because I’m just finishing with The Nice. I can’t take The Nice a lot further and I’m thinking of moving on. I wonder if we could form a band together?"

That was such an interesting thought because Keith’s background was European influenced music, the same way King Crimson’s was European influenced.

And that almost defines progressive music – although I don’t like the term progressive music – but, anyway, Keith and I decided to form a band together and that was the beginning of ELP.

RM: It sounds like it was almost a case of musical fate…

GL: Honestly, it was an absolute coincidence! But yes I also appeared on the second King Crimson album simply because at that time Robert hadn’t really gotten anybody to replace me.

He wanted to get on with the record so I said "I don’t mind doing the vocals until you find someone."

So I did a couple of tracks on that record as well.

RM: Just as an aside, I’m sure you will have read or heard that Robert recently confirmed he is stepping away from music – primarily because of his disillusionment with the business aspect of the industry and the change in relationship between artist and label.

There have been massive changes in music over the decades and perhaps most significantly in recent times; can you understand Robert’s frustrations and see where he’s coming from?

GL: I don’t know. I think Robert’s had a very good run with the idea of King Crimson and maybe he’s reached a point where he’s had enough of it, you know?

If you’re in it just for the business then I can understand that it isn’t as great as it used to be, in many ways. But I’m not in it for the business, I’m in it for the music.

This is not a job to me so if it’s not work, why would I stop doing it?

If the business stops I’ll still play the music. I played the music before the business started [laughs] and I’ll be playing the music when the business stops for me.

The business, really, is a by-product of the music and it’s a fortunate one because I’m able to live from it and it’s able to pay for my life. And that’s a great thing.

But you’d have to ask Robert why he has had enough or why he wants to walk away; he’s made his contribution and if he feels the time has come for him to not do that then he’s probably wise to step out and not do it for a while. And maybe he’ll come back and maybe he won’t.

RM: Indeed; only musical time will tell if he does or not. I hope he does.

Moving on from Robert and King Crimson to Keith, Carl Palmer and ELP...

I have to start by telling you that a few years ago I drafted out my Top 20 list of all-time favourite albums and only one band appeared more than once – Emerson Lake and Palmer.

The specific albums were Brain Salad Surgery, one of ELP’s finest and most innovative records, and Works Volume 1. But I know you feel Works Volume 1 heralded in the beginning of the end for ELP and the start of the separation – no more than the sum of their parts as opposed to a cohesive trio…

GL: Yes.

RM: But each of you, individually, produced an excellent solo side of music before reconvening for a great ELP side. Works Volume 1 holds up extremely well…

GL: It does and it is a great record. I do believe it’s a great record.

But, the first five albums – Emerson Lake and Palmer, Tarkus, Pictures at an Exhibition, Trilogy and Brain Salad Surgery – all of those records had a unique and innovative power about them, creatively.

They were different. They really were the sound and the soul and the energy of Emerson Lake and Palmer.

There was no other thing like them. The band had a real sound to it and they were very powerful, very dynamic records.

In some ways they were often very beautiful records, like the track Trilogy for example or some of the ballads such as Still You Turn Me On, Lucky Man, or From the Beginning.

Then there's Karn Evil 9 and "Welcome back my friends…" These were really the creative highlights, for me anyway, of ELP.

When it came to Works Volume 1, although it was a great record it kind of was the beginning of the end. Instead of being Emerson Lake and Palmer and the sound of Emerson Lake and Palmer it was the sound of orchestras. Or ELP through the voice of an orchestra, to a large degree.

RM: That’s a fair point. I just happen to love that.

GL: But it was also each of us going off in our individual directions, so it was like a fragmented version of ELP. But I can look back at that album and think there were a lot of really, lovely tracks on there.

Pirates I like for example, very much.

RM: Well I hope we have time to elaborate because, funnily enough, if I’m discussing desert island tracks I have six, specific all-time favourite songs. And Pirates is one of those songs.

It's just such a majestic piece of work.

GL: Oh it’s just a lovely thing and it wasn’t one of those songs which, obviously, ever got a lot of radio play. But, if you get into it, it really is a little masterpiece.

It tells a story, it’s full of colourful pictures, the music’s dramatic… Leonard Bernstein liked it.

RM: I’m not surprised. When people talk to me about Pirates or I’m trying to put across why I feel it’s such an important composition I always say it’s the soundtrack to the greatest pirate film never made.

GL: It is, you’re absolutely right. In fact, funnily enough, somebody did an amateur collage of pirate images to match the music and it was really stunning.

But we couldn’t put it out, because it would require so much copyright clearance it wouldn’t make sense.

But it was the most brilliant thing, it really illustrated the visions of what the song says.

So, yeah, I love Pirates from that record; I also love Closer to Believing.

RM: Oh that’s a beautiful song. Funny you should mention that particular track as well, because it ties in to what you were saying earlier about different songs and how important they are to different people…

I’m a 70s rock boy at heart and in that decade would be listening to a lot of progressive music, some jazz-fusion and a lot of late 60s material.

My parents were very much into 50s music – swing, big band, the crooners – but when I played songs like Closer to Believing and C’est la Vie and they took to them immediately.

My mum loved Closer to Believing and my dad loved C’est la Vie so, again, we have songs crossing genres and generations.

GL: C’est la Vie is a nice song. I lived in Paris for a while and that’s one of the stories I tell on stage.

I do C’est la Vie in the show and I’ve always had a love for that French sound…

GL: The French are very emotional as are some of their songs. If you listen to Edith Piaf, for example, you’ll hear a lot of emotion in her voice. So that was one of the things I wanted to capture in one of my writings, because it just had that passion. And it’s great for a ballad singer to sing.

In fact Johnny Hallyday, the French Elvis Presley, had a Number One hit with C’est la Vie in France.

RM: And those songs continue to travel. Truly timeless music and beautiful lyrics.

Talking of lyrics, if I could jump back to Pirates. It’s not just the words that tell the story, it’s their subtle or dramatic nuances, the phrasing, the way you put those lyrics across.

You and co-lyricist Peter Sinfield worked on those lyrics for an incredibly long time…

GL: We created it (the lyric), strangely enough, in a chalet way up on a Swiss mountain, outside of Montreaux. It was above the clouds, right up in the snow.

We cut ourselves off up there and we had bought a lot of books about piracy – proper literature, historical studies – and we brought films and videos to watch.

And we just literally bathed in this stuff twenty-four hours a day and we wrote and wrote and wrote… until we had it done. And that’s why it’s full of those great visions [delivers in dramatic, narrative style]:

"The Captain rose from a silk divan with a pistol in his fist.

And shot the lock from an iron box and a blood red ruby kissed.

'I give you jewellery of turquoise, a crucifix of solid gold.

One hundred thousand silver pieces – it is just as I foretold!' "

Lovely, piratical language!

RM: Your delivery of those lines confirms just what a strong and poetic lyric it is.

In fact it would make a wonderful poem…

GL: Well, it is. It’s really poetry that’s set to music. And the music’s great too.

Keith wrote some fabulous stuff and it's one of the nicest things the band ever did so so I can understand why you would say Works Volume 1 is a lovely record. It is indeed a lovely record.

But it is the end of the lovely records for me. ELP made other albums but they did not have the hallmark, the originality or the creative honesty of those early records.

After Works Volume 1? I think they were records made for a reason, and the reasons weren’t quite right.

RM: I don’t disagree. Works Volume 2 was more commercial but it was also half-compilation.

And now that we’ve led on to this, I can't not ask about the one album very few people raise in interview or just don’t want to talk about [laughs]. Love Beach was the final album of ELP's initial nine-year run...

GL: That's right...

RM: ...and is a very controversial album in the sense that there have been so many different takes on it.

Carl instantly dismissed it with his well-known comment about the record making "a good frisbee," while Keith has always maintained there are some fine moments on the album.

I think we all agree the packaging condemned it before anyone had a chance to give it a fair hearing but I would be interested in your own thoughts.

Nearly thirty-five years on, can you take anything from Love Beach?

GL: What I can take from it is it’s an album we never wanted to make – we were forced to make it really because it was a contractual commitment.

Having said that, once we decided to make it we got on with it and made it as good as we could; we gave it everything we had.

RM: I’m somewhere in the middle ground. I love The Gambler, with it's quirky charm reminiscent of tracks such as The Sheriff and Jeremy Bender and Memoirs is seriously under-rated – probably because it sits on the Love Beach album. I think that’s a lovely, lyrical suite of music.

GL: Officer and a Gentlemen, all of that?

RM: Yes; side two in old vinyl terms

GL: Yeah, there were some very good ideas on there and they were executed pretty well; the only problem was we knew it was over at that point, really.

It wasn’t that no-one cared; it was just that the idea was to get it done as opposed to just focusing on the music. There was this feeling of delivering a product and, although we did our best creatively, I still feel it lacks strength when compared to the earlier records.

RM: Which relates to what you were saying earlier about the business. You’re seeing the business side dominate during the Love Beach period – you had to deliver, you had to produce product.

GL: Yes, and for example I didn’t produce that record; I just didn’t feel I had my heart in it to produce it.

I had my heart in it to perform it and to write it, but as a producer I just didn’t have a vision for it.

I know that must sound strange to you – on the one hand I made the record as an artist but on the other hand, as a producer, I didn’t have that same vision of hearing it in my head as I did for albums like Tarkus, Trilogy, Brain Salad Surgery.

Those records, and the first album, I had almost a sense of how they should sound.

RM: No, I can understand that and, actually, that’s a very telling statement.

You referred before to the "creative honesty" of the earlier albums but with Love Beach you didn’t have that creative honesty – so you didn’t have the personal honesty to produce it.

You could have done it, clearly, but it would have been for the wrong reasons. You didn’t have that vision for it, didn’t have that direction…

GL: I just became the artist at that point. I was just the member of this band and we were making a record. I don’t know if there was a producer at all, it just got done…

RM: I think Keith produced, or at least was credited for the production.

In fact Johnny Hallyday, the French Elvis Presley, had a Number One hit with C’est la Vie in France.

RM: And those songs continue to travel. Truly timeless music and beautiful lyrics.

Talking of lyrics, if I could jump back to Pirates. It’s not just the words that tell the story, it’s their subtle or dramatic nuances, the phrasing, the way you put those lyrics across.

You and co-lyricist Peter Sinfield worked on those lyrics for an incredibly long time…

GL: We created it (the lyric), strangely enough, in a chalet way up on a Swiss mountain, outside of Montreaux. It was above the clouds, right up in the snow.

We cut ourselves off up there and we had bought a lot of books about piracy – proper literature, historical studies – and we brought films and videos to watch.

And we just literally bathed in this stuff twenty-four hours a day and we wrote and wrote and wrote… until we had it done. And that’s why it’s full of those great visions [delivers in dramatic, narrative style]:

"The Captain rose from a silk divan with a pistol in his fist.

And shot the lock from an iron box and a blood red ruby kissed.

'I give you jewellery of turquoise, a crucifix of solid gold.

One hundred thousand silver pieces – it is just as I foretold!' "

Lovely, piratical language!

RM: Your delivery of those lines confirms just what a strong and poetic lyric it is.

In fact it would make a wonderful poem…

GL: Well, it is. It’s really poetry that’s set to music. And the music’s great too.

Keith wrote some fabulous stuff and it's one of the nicest things the band ever did so so I can understand why you would say Works Volume 1 is a lovely record. It is indeed a lovely record.

But it is the end of the lovely records for me. ELP made other albums but they did not have the hallmark, the originality or the creative honesty of those early records.

After Works Volume 1? I think they were records made for a reason, and the reasons weren’t quite right.

RM: I don’t disagree. Works Volume 2 was more commercial but it was also half-compilation.

And now that we’ve led on to this, I can't not ask about the one album very few people raise in interview or just don’t want to talk about [laughs]. Love Beach was the final album of ELP's initial nine-year run...

GL: That's right...

RM: ...and is a very controversial album in the sense that there have been so many different takes on it.

Carl instantly dismissed it with his well-known comment about the record making "a good frisbee," while Keith has always maintained there are some fine moments on the album.

I think we all agree the packaging condemned it before anyone had a chance to give it a fair hearing but I would be interested in your own thoughts.

Nearly thirty-five years on, can you take anything from Love Beach?

GL: What I can take from it is it’s an album we never wanted to make – we were forced to make it really because it was a contractual commitment.

Having said that, once we decided to make it we got on with it and made it as good as we could; we gave it everything we had.

RM: I’m somewhere in the middle ground. I love The Gambler, with it's quirky charm reminiscent of tracks such as The Sheriff and Jeremy Bender and Memoirs is seriously under-rated – probably because it sits on the Love Beach album. I think that’s a lovely, lyrical suite of music.

GL: Officer and a Gentlemen, all of that?

RM: Yes; side two in old vinyl terms

GL: Yeah, there were some very good ideas on there and they were executed pretty well; the only problem was we knew it was over at that point, really.

It wasn’t that no-one cared; it was just that the idea was to get it done as opposed to just focusing on the music. There was this feeling of delivering a product and, although we did our best creatively, I still feel it lacks strength when compared to the earlier records.

RM: Which relates to what you were saying earlier about the business. You’re seeing the business side dominate during the Love Beach period – you had to deliver, you had to produce product.

GL: Yes, and for example I didn’t produce that record; I just didn’t feel I had my heart in it to produce it.

I had my heart in it to perform it and to write it, but as a producer I just didn’t have a vision for it.

I know that must sound strange to you – on the one hand I made the record as an artist but on the other hand, as a producer, I didn’t have that same vision of hearing it in my head as I did for albums like Tarkus, Trilogy, Brain Salad Surgery.

Those records, and the first album, I had almost a sense of how they should sound.

RM: No, I can understand that and, actually, that’s a very telling statement.

You referred before to the "creative honesty" of the earlier albums but with Love Beach you didn’t have that creative honesty – so you didn’t have the personal honesty to produce it.

You could have done it, clearly, but it would have been for the wrong reasons. You didn’t have that vision for it, didn’t have that direction…

GL: I just became the artist at that point. I was just the member of this band and we were making a record. I don’t know if there was a producer at all, it just got done…

RM: I think Keith produced, or at least was credited for the production.

The changing faces of ELP. Brain Salad Surgery, with iconic H. R. Giger cover, is a progressive

rock tour de force. But the ELPee Gees cover of Love Beach condemned the album before the

record even made it out the sleeve.

rock tour de force. But the ELPee Gees cover of Love Beach condemned the album before the

record even made it out the sleeve.

GL: After that, for various reasons, we used outside producers. But that didn’t work either, really.

Black Moon, for example, was produced by Mark Mancina. Fantastic producer, just fantastic.

Great musician too, but it was ELP by deferment. Instead of us making the record it was us playing the record for him to make. So those later albums, once again, didn’t have that hallmark of the individual, innovative, creative power of the band Emerson Lake and Palmer.

It was Emerson Lake and Palmer making an ELP record for a producer.

RM: That’s really interesting and, again, quite telling, because a lot of fans, myself included, would love to have you, Keith and Carl get back in the studio – even just one more time – to see what you could create with no outside influences to see and hear where ELP would be now, musically…

GL: When the idea came to reform ELP – this was to do Black Moon – I did say "Let’s return to the formula we used at the start" which was to let me produce the record and basically make the record ourselves.

But Keith and Carl didn’t want to do that, they wanted to use an outside producer.

Rather than stamp my feet and say no, it’s my way or the highway I agreed to it. I said "okay, if that’s the way the majority of the band wants to make the record then so be it."

Because who was to say whether it would be better or not?

But in retrospect, and as much as I love Mark Mancina and I love his musicality and I love his skills as a producer – and I’m a close friend of his to this day – it wasn’t the Emerson Lake and Palmer that was the platinum success. It wasn’t the electrifying musical powerhouse it was during those early albums.

RM: But that’s a testament to the standards you set yourselves, Greg. Black Moon and In the Hot Seat are not bad albums...

GL: No, they’re not…

RM: ...but, when compared to the musical standards you set yourselves and the heights you had achieved, they are not close to matching your best works.

GL: No, the best work got created when there was no-one else in the room.

There was the chemistry – unfettered, un-interfered with – the clean chemistry of Emerson Lake and Palmer. And the fact that I produced it was almost incidental; someone had to do it and it was me [laughs].

I knew more than anyone else about recording studios and recording techniques so it kind of fell to me but in a way it was just the fact that we all made the record together, alone, in the studio.

RM: Something I recall very clearly from right after that era – 1975, during the post-Brain Salad Surgery pre-Works hiatus – was an article on ELP that included an interview with you.

One question was "How long can ELP last?" to which you replied "How long is a piece of string?"

GL: The sort of question where you can't possibly know the answer [laughs].

The reality of it is none of these bands last forever – well, except for the Rolling Stones! [laughs] – but, truthfully, none of them remain creative forever.

There is a passage of time – it could be three albums, it could be five, it could be six – but it’s never fifteen, you know? It doesn’t go on forever.

RM: Absolutely, but to return to our "piece of string" – could you have honestly conceived back then that piece of string would turn out to be forty years long, in terms of a 40th anniversary reunion show at the High Voltage Festival in 2010?

GL: Oh no, but I think the better and more artistic the creations are the longer they’ll endure, like In the Court of the Crimson King. The reason it has endured as long as it has is because it’s high quality, nothing more nothing less. It’s just high quality, artistically.

RM: Yes, it has a remarkably high value artistically. And you don’t have to use words like progressive, it simply has artistic merit. That’s what it comes down to.

GL: It’s as clear as that and, I would say, was an album made for that reason. It was made as a work of art.

It wasn’t made as a pop record; it wasn’t even made as a rock record. It was made as a work of art.

That’s what we wanted it to be and that’s what it was. And that’s probably why it’s lasted as long as it has.

RM: I would agree with that. More than forty years on people still cite it, still rate it, still talk about it and I don’t think that will ever dissipate. I think it will continue to resonate…

GL: I think it will and I think even a hundred years on it will have some interest for people. People will look back and say "See what type of record they were making then? Look, this is what was happening!"

RM: Yes, it's a musical marker.

GL: I also think that record shone a light into the future in some way. I couldn’t really be specific and tell you how or why; but I’m quite sure that it did.

In some sense it shone a light into the future of a new way of approaching and playing music.

RM: I think so. I would put it alongside Pet Sounds by The Beach Boys and Sgt. Pepper by The Beatles.

Truly influential, innovative and important studio records.

GL: Well, undoubtedly the first people who really moved away from taking their influences from American music – blues, soul, gospel, country – and started probing European music influences, Indian music and all the rest, was The Beatles. And there’s no question they were the greatest band on earth.

RM: My wife will be nodding in sage agreement and giving that particular comment the thumbs up [laughs]. For her it’s The Beatles and The Moody Blues.

GL: Funnily enough I’m doing a show with the Moody Blues next March – a Caribbean cruise!

RM: Yes, The Voyage Cruise shows. The press and promotional adverts are running now.

GL: Yeah, it’s the Moody Blues and me. [announces] "Come on board for the Caribbean and hear the Moody Blues and Greg Lake" That’s not a bad deal!

RM: [laughs] No, it's not, but it's far more likely we’ll be continuing our conversation in Glasgow!

Greg, thanks for giving so much of your time to FabricationsHQ.

GL: It's been lovely talking to you Ross and it would be lovely to see you in Glasgow.

Come and see the show!

Black Moon, for example, was produced by Mark Mancina. Fantastic producer, just fantastic.

Great musician too, but it was ELP by deferment. Instead of us making the record it was us playing the record for him to make. So those later albums, once again, didn’t have that hallmark of the individual, innovative, creative power of the band Emerson Lake and Palmer.

It was Emerson Lake and Palmer making an ELP record for a producer.

RM: That’s really interesting and, again, quite telling, because a lot of fans, myself included, would love to have you, Keith and Carl get back in the studio – even just one more time – to see what you could create with no outside influences to see and hear where ELP would be now, musically…

GL: When the idea came to reform ELP – this was to do Black Moon – I did say "Let’s return to the formula we used at the start" which was to let me produce the record and basically make the record ourselves.

But Keith and Carl didn’t want to do that, they wanted to use an outside producer.

Rather than stamp my feet and say no, it’s my way or the highway I agreed to it. I said "okay, if that’s the way the majority of the band wants to make the record then so be it."

Because who was to say whether it would be better or not?

But in retrospect, and as much as I love Mark Mancina and I love his musicality and I love his skills as a producer – and I’m a close friend of his to this day – it wasn’t the Emerson Lake and Palmer that was the platinum success. It wasn’t the electrifying musical powerhouse it was during those early albums.

RM: But that’s a testament to the standards you set yourselves, Greg. Black Moon and In the Hot Seat are not bad albums...

GL: No, they’re not…

RM: ...but, when compared to the musical standards you set yourselves and the heights you had achieved, they are not close to matching your best works.

GL: No, the best work got created when there was no-one else in the room.

There was the chemistry – unfettered, un-interfered with – the clean chemistry of Emerson Lake and Palmer. And the fact that I produced it was almost incidental; someone had to do it and it was me [laughs].

I knew more than anyone else about recording studios and recording techniques so it kind of fell to me but in a way it was just the fact that we all made the record together, alone, in the studio.

RM: Something I recall very clearly from right after that era – 1975, during the post-Brain Salad Surgery pre-Works hiatus – was an article on ELP that included an interview with you.

One question was "How long can ELP last?" to which you replied "How long is a piece of string?"

GL: The sort of question where you can't possibly know the answer [laughs].

The reality of it is none of these bands last forever – well, except for the Rolling Stones! [laughs] – but, truthfully, none of them remain creative forever.

There is a passage of time – it could be three albums, it could be five, it could be six – but it’s never fifteen, you know? It doesn’t go on forever.

RM: Absolutely, but to return to our "piece of string" – could you have honestly conceived back then that piece of string would turn out to be forty years long, in terms of a 40th anniversary reunion show at the High Voltage Festival in 2010?

GL: Oh no, but I think the better and more artistic the creations are the longer they’ll endure, like In the Court of the Crimson King. The reason it has endured as long as it has is because it’s high quality, nothing more nothing less. It’s just high quality, artistically.

RM: Yes, it has a remarkably high value artistically. And you don’t have to use words like progressive, it simply has artistic merit. That’s what it comes down to.

GL: It’s as clear as that and, I would say, was an album made for that reason. It was made as a work of art.

It wasn’t made as a pop record; it wasn’t even made as a rock record. It was made as a work of art.

That’s what we wanted it to be and that’s what it was. And that’s probably why it’s lasted as long as it has.

RM: I would agree with that. More than forty years on people still cite it, still rate it, still talk about it and I don’t think that will ever dissipate. I think it will continue to resonate…

GL: I think it will and I think even a hundred years on it will have some interest for people. People will look back and say "See what type of record they were making then? Look, this is what was happening!"

RM: Yes, it's a musical marker.

GL: I also think that record shone a light into the future in some way. I couldn’t really be specific and tell you how or why; but I’m quite sure that it did.

In some sense it shone a light into the future of a new way of approaching and playing music.

RM: I think so. I would put it alongside Pet Sounds by The Beach Boys and Sgt. Pepper by The Beatles.

Truly influential, innovative and important studio records.

GL: Well, undoubtedly the first people who really moved away from taking their influences from American music – blues, soul, gospel, country – and started probing European music influences, Indian music and all the rest, was The Beatles. And there’s no question they were the greatest band on earth.

RM: My wife will be nodding in sage agreement and giving that particular comment the thumbs up [laughs]. For her it’s The Beatles and The Moody Blues.

GL: Funnily enough I’m doing a show with the Moody Blues next March – a Caribbean cruise!

RM: Yes, The Voyage Cruise shows. The press and promotional adverts are running now.

GL: Yeah, it’s the Moody Blues and me. [announces] "Come on board for the Caribbean and hear the Moody Blues and Greg Lake" That’s not a bad deal!

RM: [laughs] No, it's not, but it's far more likely we’ll be continuing our conversation in Glasgow!

Greg, thanks for giving so much of your time to FabricationsHQ.

GL: It's been lovely talking to you Ross and it would be lovely to see you in Glasgow.

Come and see the show!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Greg Lake

October 2012

Muirsical Conversation with Greg Lake

October 2012

Greg Lake official website: http://www.greglake.com/

Featured audio tracks presented to accompany the above article and to promote the work of the artists.

No infringement of copyright is intended.

For Those Who Dare from Greg Lake (solo, 1981)

The Court of the Crimson King from In the Court of the Crimson King (King Crimson, 1969)

C'est la Vie from Works Volume 1 (ELP, 1977)

Karn Evil 9: 1st Impression from Brain Salad Surgery (ELP, 1973)

Photo Credit: lrheath/ wikipedia