Charitable intimacy

Muirsical Conversation with Dan Patlansky

Muirsical Conversation with Dan Patlansky

In 2014 award winning South African guitarist Dan Patlansky garnered deserved attention in the UK with his highly impacting seventh album, Dear Silence Thieves.

Introvertigo (2016) and Perfection Kills (2018) were no less impressive, featuring feisty finger flexing and more delicate, slow blues tones across the fretboard of Dan Patlansky’s vintage Fender Strats.

(Said guitars have now been retired and replaced by a Masterbuilt Jason Smith Fender Strat, which cleverly doubles as a replica of Dan Patlansky’s much loved 'Beast' model).

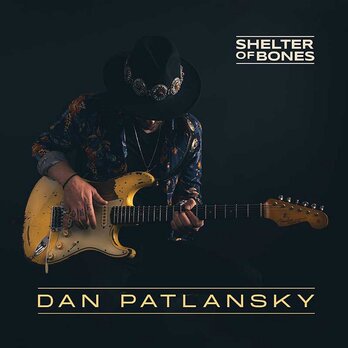

Four years later and nearly three years in the making came Shelter of Bones, an album that carries that trademark Dan Patlansky sound (bolstered by his new Masterbuilt Strat) but also takes a couple of sonic twists and softer, texture laden turns.

Now, in the spring of 2023, Dan Patlansky returns to British shores for an intimate club tour (dates at end of this article) that reinforces the credentials of Shelter of Bones and road tests a clutch of brand new songs that will feature on Patlansky's next album.

The tour, which includes eight dates in Europe, also supports the Nordoff and Robbins Music Therapy, a charitabe organization whose raison d'être is close to the heart of Dan Patlansky.

On the eve of the upcoming tour FabricationsHQ revisits a 2022 Shelter of Bones interview with Dan Patlansky, bolstered by a new and extended conversation with the noted guitarist discussing the pros of field testing new songs in front of a live audience, the reason (and love) for an intimate club shows and his support for Nordoff and Robbins.

But the conversation started with Dan Patlansky's fondness for touring the UK...

Introvertigo (2016) and Perfection Kills (2018) were no less impressive, featuring feisty finger flexing and more delicate, slow blues tones across the fretboard of Dan Patlansky’s vintage Fender Strats.

(Said guitars have now been retired and replaced by a Masterbuilt Jason Smith Fender Strat, which cleverly doubles as a replica of Dan Patlansky’s much loved 'Beast' model).

Four years later and nearly three years in the making came Shelter of Bones, an album that carries that trademark Dan Patlansky sound (bolstered by his new Masterbuilt Strat) but also takes a couple of sonic twists and softer, texture laden turns.

Now, in the spring of 2023, Dan Patlansky returns to British shores for an intimate club tour (dates at end of this article) that reinforces the credentials of Shelter of Bones and road tests a clutch of brand new songs that will feature on Patlansky's next album.

The tour, which includes eight dates in Europe, also supports the Nordoff and Robbins Music Therapy, a charitabe organization whose raison d'être is close to the heart of Dan Patlansky.

On the eve of the upcoming tour FabricationsHQ revisits a 2022 Shelter of Bones interview with Dan Patlansky, bolstered by a new and extended conversation with the noted guitarist discussing the pros of field testing new songs in front of a live audience, the reason (and love) for an intimate club shows and his support for Nordoff and Robbins.

But the conversation started with Dan Patlansky's fondness for touring the UK...

Ross Muir: Since your emergence from outside your own borders with Dear Silence Thieves, you’ve played the UK many times; indeed this spring 2023 tour follows almost exactly one year on from the last time you played our shores. You clearly have a love for the UK and the British blues fans.

Dan Patlansky: I genuinely find there is a certain amount of savvy in the UK; it’s a very educated audience, I feel, compared to a lot of other countries.

Now, you can have a great time, and a great gig, in many different countries but I do find, in the UK, that people know what they like and are very educated on the stuff they are listening to.

But in one way that’s also quite daunting, because you’ve got to get up there and you’ve got to really give it, you know?

RM: You really have to deliver.

DP: Exactly, you’ve got to deliver; it can’t just be a half-arsed type of show but that’s great; I love that.

It pushes us as musicians because you know you’ve got a very educated audience in front of you.

I absolutely love touring the UK for that very reason.

RM: And I think that’s reciprocated through respect and reaction; you wouldn’t get away with half-arsed, because British audiences, and certainly Glasgow audiences since way back in the day, can suss very quickly when somebody is genuine and when somebody is dialling it in.

On this tour I believe you have your South African band-mates over with you?

DP: Yes, I’m bringing my South African band this time around, and the reason for that is because of the way we have structured this particular set; we’ve added six new tunes that no-one has ever heard before, that will be on the new album.

When you have so many brand new songs it takes a lot of rehearsal; what I normally do, after I fly into the UK, is we jump into a rehearsal room, we rehearse the set for a couple of hours and then we go and play.

And that’s fine, because the songs we are playing have already been recorded and arranged, so I can send those songs over to the guys I usually use over here, and they have something to listen to.

But at this point we don’t, because absolutely nothing new has been recorded! In fact the last of those six songs was only finished earlier this month!

The whole reason we’re doing it, and this goes back to bands of yesteryear, was part of getting songs honed, arranged and ready for recording, was touring them; it really was – you take them out on the road to see if an audience reacts to them in a favourable way, or, meh [laughs], which is not quite the way you thought it was gonna be!

But that’s amazing too because after a few months of touring, the way you thought a song was going to be, all of a sudden it morphs into a different thing altogether; other parts come into play, or you drop certain other parts.

All of a sudden the song has become something special.

And that’s what I want – I want the songs, when recorded for the album, to represent how we have played them live; that’s the magic you discover in front of a live audience.

RM: Is it fair to say then, given the business – if that’s even the word the right word anymore – has changed so dramatically that the long-lost A&R man is now replaced by an A&R audience?

You're gauging their reactions and thinking "OK, maybe the bridge has to change" or "this song clearly has to be shorter to hold attention."

DP: That’s exactly what it is; you’re using that audience and, let’s be honest, an audience is the best sounding board, because that’s who you have to convince – especially as you said in a place like Glasgow.

They are not going to lie to you and you’re going to know – it’s like when a golfer puts a short putt in before moving to the next hole?

RM: The polite ripple of applause…

DP: Yes, exactly, that quiet applause and "yes, very nice... what else have you got?" [loud laughter]

But, when you get into situations like that, you can quickly understand what is not working – like you mentioned maybe the song is too long, or it’s the wrong tempo, maybe the chorus needs reworking, whatever the case.

So for me that’s what I’m really excited about, testing the new songs out.

RM: On the subject of Glasgow we have one of our blues rock sons supporting you with an acoustic set, Stevie Nimmo...

DP: When I was told that Stevie was support for that show I was jumping up and down!

I’m a big fan of Stevie, and Alan Nimmo, obviously; I’ve toured with King King a lot, done a few festivals where Stevie has also been on the bill and played with him in the Netherlands, all that sort of stuff.

I reconnected with Stevie when I was touring in support to King King and I’ve always loved the playing and singing of both Stevie and Alan.

I’m so chuffed to be sharing a stage with Stevie and so glad he said yes; that's Glasgow and British blues rock royalty opening for me! It will make for a fantastic evening.

RM: Stevie loves playing acoustic shows to more intimate crowds but now, being part of King King, he has little time to do that; so this will be a treat for him, too.

That leads to the obvious follow-on, the smaller club intimacy of this tour which, as you have said before is, for you where the blues truly lives and thrives.

The blues, in its truest and purest form, lives and breathes in the clubs and blues bars; that’s true whether it be Glasgow, Johannesburg or the south side of Chicago.

DP: I agree completely, and I really do notice a difference.

I started off in South Africa on the club scene with those packed rooms and the energy, and feel, that comes with it – it’s that two way connection between the guys on stage and the audience; they give you something back and you give something even more back to the audience. That’s the cycle that happens.

But when we started moving to bigger venues in South Africa, that was a massive adjustment for me because all of a sudden, I lost my connection with the audience.

Playing to larger crowds in a much bigger room is great, but I honestly felt that part of what it’s supposed to be, kind of died. I was battling to get that connection back but it was just like a brick wall between band and audience; you can’t see the white of people’s eyes; you can’t see the reaction in their faces; you can’t feel that energy – in fact it’s just too big to feel anything.

That’s why I absolutely love the small rooms, and that’s especially easy in the UK, where you have a vast array of different sized venues in every major city to choose from, from very intimate rooms to large arenas. But I’ve always loved that feeling of playing in a small room where you can connect with everyone – that’s the main reason why I picked the smaller club venues on this tour.

RM: I’ve seen and heard blues played in clubs to a hundred people; I’ve seen and heard blues played to a cast of thousands in large auditoriums; but, when it’s the latter, I hear the blues but I don’t feel the blues.

To use your good self as an example; in larger halls, when you crank out a thick riffed, muscly, blues rawk number? That works well. Songs such as Backbite carry a big sounding resonance wherever you play them.

But when you drop to a soul-blues, or musically explore with your guitar on a slow blues, you need that intimacy, you need that connection, you need that direct link to your audience – and vice versa.

DP: You really do need that connection, man, absolutely. That's when you can hear the guitar bouncing off that back wall, because it's not that far away – it’s not one hundred yards away in an arena, it’s just there!

All the stuff I grew up listening to and loved – in terms of live recordings – were all recorded in smaller clubs, with maybe one hundred and fifty people maximum crammed into a small space.

That for me is where and when the magic really seems to happen; this unexplainable thing that just seems occur between band and audience. The audience almost become part of the band; you can feel them as if they are almost on stage with you. It's a special thing, man.

RM: I think a part of that is while we all have, and love, our own favourite genres of music – rock, jazz, pop, prog, metal, what-have-you, the blues has deeper roots.

Most of us have, or will, live the blues at some point. Blues, as a human condition, goes deeper than the music.

DP: It really does. Everything in the blues is based on, and comes out of, feel and emotion.

For me, that’s also the toughest thing about being a blues musician, being able to tap into those emotions and getting that feel every night; it’s not something where you can just switch a button on and go "OK, here we go, we’re going to play a song from this chord to that chord, sing the lyrics and play these notes."

It’s a far deeper type of thing with the blues.

The great shows, again for me, are the ones where it’s completely based on feel – to the degree that you almost can’t remember the show you just played!

It feels like the whole thing took two minutes and suddenly you’ve played your encore, you’re backstage and you’re thinking "what happened?"

Those are the special nights because you’re not thinking about it – you’re just letting it all come naturally out, through feel and emotion.

And in the intimate venues, as we’ve just been taking about, it’s far easier to draw that sort of emotion out; not least because you can feel the connection to the other humans in the room...

Dan Patlansky: I genuinely find there is a certain amount of savvy in the UK; it’s a very educated audience, I feel, compared to a lot of other countries.

Now, you can have a great time, and a great gig, in many different countries but I do find, in the UK, that people know what they like and are very educated on the stuff they are listening to.

But in one way that’s also quite daunting, because you’ve got to get up there and you’ve got to really give it, you know?

RM: You really have to deliver.

DP: Exactly, you’ve got to deliver; it can’t just be a half-arsed type of show but that’s great; I love that.

It pushes us as musicians because you know you’ve got a very educated audience in front of you.

I absolutely love touring the UK for that very reason.

RM: And I think that’s reciprocated through respect and reaction; you wouldn’t get away with half-arsed, because British audiences, and certainly Glasgow audiences since way back in the day, can suss very quickly when somebody is genuine and when somebody is dialling it in.

On this tour I believe you have your South African band-mates over with you?

DP: Yes, I’m bringing my South African band this time around, and the reason for that is because of the way we have structured this particular set; we’ve added six new tunes that no-one has ever heard before, that will be on the new album.

When you have so many brand new songs it takes a lot of rehearsal; what I normally do, after I fly into the UK, is we jump into a rehearsal room, we rehearse the set for a couple of hours and then we go and play.

And that’s fine, because the songs we are playing have already been recorded and arranged, so I can send those songs over to the guys I usually use over here, and they have something to listen to.

But at this point we don’t, because absolutely nothing new has been recorded! In fact the last of those six songs was only finished earlier this month!

The whole reason we’re doing it, and this goes back to bands of yesteryear, was part of getting songs honed, arranged and ready for recording, was touring them; it really was – you take them out on the road to see if an audience reacts to them in a favourable way, or, meh [laughs], which is not quite the way you thought it was gonna be!

But that’s amazing too because after a few months of touring, the way you thought a song was going to be, all of a sudden it morphs into a different thing altogether; other parts come into play, or you drop certain other parts.

All of a sudden the song has become something special.

And that’s what I want – I want the songs, when recorded for the album, to represent how we have played them live; that’s the magic you discover in front of a live audience.

RM: Is it fair to say then, given the business – if that’s even the word the right word anymore – has changed so dramatically that the long-lost A&R man is now replaced by an A&R audience?

You're gauging their reactions and thinking "OK, maybe the bridge has to change" or "this song clearly has to be shorter to hold attention."

DP: That’s exactly what it is; you’re using that audience and, let’s be honest, an audience is the best sounding board, because that’s who you have to convince – especially as you said in a place like Glasgow.

They are not going to lie to you and you’re going to know – it’s like when a golfer puts a short putt in before moving to the next hole?

RM: The polite ripple of applause…

DP: Yes, exactly, that quiet applause and "yes, very nice... what else have you got?" [loud laughter]

But, when you get into situations like that, you can quickly understand what is not working – like you mentioned maybe the song is too long, or it’s the wrong tempo, maybe the chorus needs reworking, whatever the case.

So for me that’s what I’m really excited about, testing the new songs out.

RM: On the subject of Glasgow we have one of our blues rock sons supporting you with an acoustic set, Stevie Nimmo...

DP: When I was told that Stevie was support for that show I was jumping up and down!

I’m a big fan of Stevie, and Alan Nimmo, obviously; I’ve toured with King King a lot, done a few festivals where Stevie has also been on the bill and played with him in the Netherlands, all that sort of stuff.

I reconnected with Stevie when I was touring in support to King King and I’ve always loved the playing and singing of both Stevie and Alan.

I’m so chuffed to be sharing a stage with Stevie and so glad he said yes; that's Glasgow and British blues rock royalty opening for me! It will make for a fantastic evening.

RM: Stevie loves playing acoustic shows to more intimate crowds but now, being part of King King, he has little time to do that; so this will be a treat for him, too.

That leads to the obvious follow-on, the smaller club intimacy of this tour which, as you have said before is, for you where the blues truly lives and thrives.

The blues, in its truest and purest form, lives and breathes in the clubs and blues bars; that’s true whether it be Glasgow, Johannesburg or the south side of Chicago.

DP: I agree completely, and I really do notice a difference.

I started off in South Africa on the club scene with those packed rooms and the energy, and feel, that comes with it – it’s that two way connection between the guys on stage and the audience; they give you something back and you give something even more back to the audience. That’s the cycle that happens.

But when we started moving to bigger venues in South Africa, that was a massive adjustment for me because all of a sudden, I lost my connection with the audience.

Playing to larger crowds in a much bigger room is great, but I honestly felt that part of what it’s supposed to be, kind of died. I was battling to get that connection back but it was just like a brick wall between band and audience; you can’t see the white of people’s eyes; you can’t see the reaction in their faces; you can’t feel that energy – in fact it’s just too big to feel anything.

That’s why I absolutely love the small rooms, and that’s especially easy in the UK, where you have a vast array of different sized venues in every major city to choose from, from very intimate rooms to large arenas. But I’ve always loved that feeling of playing in a small room where you can connect with everyone – that’s the main reason why I picked the smaller club venues on this tour.

RM: I’ve seen and heard blues played in clubs to a hundred people; I’ve seen and heard blues played to a cast of thousands in large auditoriums; but, when it’s the latter, I hear the blues but I don’t feel the blues.

To use your good self as an example; in larger halls, when you crank out a thick riffed, muscly, blues rawk number? That works well. Songs such as Backbite carry a big sounding resonance wherever you play them.

But when you drop to a soul-blues, or musically explore with your guitar on a slow blues, you need that intimacy, you need that connection, you need that direct link to your audience – and vice versa.

DP: You really do need that connection, man, absolutely. That's when you can hear the guitar bouncing off that back wall, because it's not that far away – it’s not one hundred yards away in an arena, it’s just there!

All the stuff I grew up listening to and loved – in terms of live recordings – were all recorded in smaller clubs, with maybe one hundred and fifty people maximum crammed into a small space.

That for me is where and when the magic really seems to happen; this unexplainable thing that just seems occur between band and audience. The audience almost become part of the band; you can feel them as if they are almost on stage with you. It's a special thing, man.

RM: I think a part of that is while we all have, and love, our own favourite genres of music – rock, jazz, pop, prog, metal, what-have-you, the blues has deeper roots.

Most of us have, or will, live the blues at some point. Blues, as a human condition, goes deeper than the music.

DP: It really does. Everything in the blues is based on, and comes out of, feel and emotion.

For me, that’s also the toughest thing about being a blues musician, being able to tap into those emotions and getting that feel every night; it’s not something where you can just switch a button on and go "OK, here we go, we’re going to play a song from this chord to that chord, sing the lyrics and play these notes."

It’s a far deeper type of thing with the blues.

The great shows, again for me, are the ones where it’s completely based on feel – to the degree that you almost can’t remember the show you just played!

It feels like the whole thing took two minutes and suddenly you’ve played your encore, you’re backstage and you’re thinking "what happened?"

Those are the special nights because you’re not thinking about it – you’re just letting it all come naturally out, through feel and emotion.

And in the intimate venues, as we’ve just been taking about, it’s far easier to draw that sort of emotion out; not least because you can feel the connection to the other humans in the room...

RM: We've spoken about the importance of showcasing or road testing new songs in the live set but we can't not mention or talk about current album, Shelter of Bones.

There’s no question your impact, and establishing yourself as part of the UK and European blues rock scene, was made in 2014 with Dear Silence Thieves, which was solidified and built upon with Introvertigo and Perfection Kills.

But Shelter of Bones is a sonically broader work with a couple more textures added to the Dan Patlansky sound. There’s also a lot of real-life lyricism here in what is your most accomplished, and clearly personal, album to date.

DP: Thank you man; that’s most appreciated. This album was really ready to go by the end of 2019; the plan was to release it in March of 2020 but we all know what happened in March of 2020!

When the entire world almost ceased to exist pretty much because of the pandemic I was told "don’t release it until you can tour it because otherwise it’s a missed opportunity."

If you’re going to tour, or when you do get back out on the road, you really want to have an album behind it.

Now, what that at gave me was this fantastic opportunity to revisit certain songs on the album and rerecord a few things I wasn’t happy with, including dropping some songs completely and rewriting a couple, all that sort of thing.

But that was a great thing and a terrible thing at the same time! Great for the obvious reasons, but when you get almost another two years to wrap your head around an album you start hearing things and over-analysing, to a point that you lose perspective of what the album is – to the extent that just before this album was released, I was convinced it was the worst thing that had ever been recorded by beast or man!

I just couldn’t hear it any more or hear what it was – so to get any feedback that said "yeah, this is a cool album," was a relief more than anything because I had lost so much perspective.

But I’m pleased I had that opportunity to really think about the album and put everything into it – like the lyrical content for example; writing about truly personal experiences and social commentary on what was on my mind over these last two years. That is certainly reflected in the final product.

RM: It is indeed. Any over-analysing has been far outweighed by the opportunity to revisit the album and, two years later, deliver it. It's an album that sounds like it has had time spent on it.

DP: Well, you know what it’s like – a band or artist is usually touring, touring and touring then it's a month off and "cool; let’s crack the album, because we need to get it going and get it done by this date!" [laughs]

You do it to the best of your ability and that approach can have its upsides, because you don’t overthink things; but I don’t think I’ll ever in my life again have the opportunity to have two years to work on an album.

That’s almost unheard of!

RM: It is, courtesy of one of the few positives to come out of Covid-19 and the pandemic lockdowns – time.

Albeit that can be a double-edged sword in that you become like the painter who just can’t stop putting that last brush stroke to the canvas.

However as regards Shelter of Bones, and to expand on my earlier "sonically broader" comment, I think you stepped back from it at just the right moment and got the balance right between your personalised lyricism, the blues raucous side of Dan Patlansky and the more atmospheric, spacious slow blues.

As regards the latter I still maintain you shine best, and are sorely underrated, when playing slow blues – the nous to know when not to play the note, and when and how to express emotively.

DP: I’m so glad you mentioned that because out of all the hundreds of interviews I’ve done no-one other than you has ever brought that up.

My comfort zone, or the platform or genre I feel most comfortable expressing myself in, has always been a slow blues type of thing; that space and that vibe; it’s always been the most natural thing for me to do.

In fact, if it was up to me, I would do a forty-five-minute album of just slow minor blues! [laughs]; I really do have that much passion for it.

You also touched on another great point. An album, even with two years of messing around on it, you never – as the artist – get to the point of saying "yeah, we’re done; that’s the album!"

You never finish an album, you always abandon an album [laughs], but you do get to the stage where you think well, I’m going to start doing harm to the album if I add any more of those brush strokes, so I’m just going to kinda leave it there and move on with my life [laughs].

You have to get to that point, but it’s tough place to be sometimes.

RM: That’s true of any art. I pride myself in how I write and how I convey in the written word but there is not one article, feature, promo piece or review of mine where I don’t go back to it at some point – it might be the very next day or months down the line – and think "why didn’t I say that" or "why didn’t I emphasise this word or line instead of that one…"

There’s no question your impact, and establishing yourself as part of the UK and European blues rock scene, was made in 2014 with Dear Silence Thieves, which was solidified and built upon with Introvertigo and Perfection Kills.

But Shelter of Bones is a sonically broader work with a couple more textures added to the Dan Patlansky sound. There’s also a lot of real-life lyricism here in what is your most accomplished, and clearly personal, album to date.

DP: Thank you man; that’s most appreciated. This album was really ready to go by the end of 2019; the plan was to release it in March of 2020 but we all know what happened in March of 2020!

When the entire world almost ceased to exist pretty much because of the pandemic I was told "don’t release it until you can tour it because otherwise it’s a missed opportunity."

If you’re going to tour, or when you do get back out on the road, you really want to have an album behind it.

Now, what that at gave me was this fantastic opportunity to revisit certain songs on the album and rerecord a few things I wasn’t happy with, including dropping some songs completely and rewriting a couple, all that sort of thing.

But that was a great thing and a terrible thing at the same time! Great for the obvious reasons, but when you get almost another two years to wrap your head around an album you start hearing things and over-analysing, to a point that you lose perspective of what the album is – to the extent that just before this album was released, I was convinced it was the worst thing that had ever been recorded by beast or man!

I just couldn’t hear it any more or hear what it was – so to get any feedback that said "yeah, this is a cool album," was a relief more than anything because I had lost so much perspective.

But I’m pleased I had that opportunity to really think about the album and put everything into it – like the lyrical content for example; writing about truly personal experiences and social commentary on what was on my mind over these last two years. That is certainly reflected in the final product.

RM: It is indeed. Any over-analysing has been far outweighed by the opportunity to revisit the album and, two years later, deliver it. It's an album that sounds like it has had time spent on it.

DP: Well, you know what it’s like – a band or artist is usually touring, touring and touring then it's a month off and "cool; let’s crack the album, because we need to get it going and get it done by this date!" [laughs]

You do it to the best of your ability and that approach can have its upsides, because you don’t overthink things; but I don’t think I’ll ever in my life again have the opportunity to have two years to work on an album.

That’s almost unheard of!

RM: It is, courtesy of one of the few positives to come out of Covid-19 and the pandemic lockdowns – time.

Albeit that can be a double-edged sword in that you become like the painter who just can’t stop putting that last brush stroke to the canvas.

However as regards Shelter of Bones, and to expand on my earlier "sonically broader" comment, I think you stepped back from it at just the right moment and got the balance right between your personalised lyricism, the blues raucous side of Dan Patlansky and the more atmospheric, spacious slow blues.

As regards the latter I still maintain you shine best, and are sorely underrated, when playing slow blues – the nous to know when not to play the note, and when and how to express emotively.

DP: I’m so glad you mentioned that because out of all the hundreds of interviews I’ve done no-one other than you has ever brought that up.

My comfort zone, or the platform or genre I feel most comfortable expressing myself in, has always been a slow blues type of thing; that space and that vibe; it’s always been the most natural thing for me to do.

In fact, if it was up to me, I would do a forty-five-minute album of just slow minor blues! [laughs]; I really do have that much passion for it.

You also touched on another great point. An album, even with two years of messing around on it, you never – as the artist – get to the point of saying "yeah, we’re done; that’s the album!"

You never finish an album, you always abandon an album [laughs], but you do get to the stage where you think well, I’m going to start doing harm to the album if I add any more of those brush strokes, so I’m just going to kinda leave it there and move on with my life [laughs].

You have to get to that point, but it’s tough place to be sometimes.

RM: That’s true of any art. I pride myself in how I write and how I convey in the written word but there is not one article, feature, promo piece or review of mine where I don’t go back to it at some point – it might be the very next day or months down the line – and think "why didn’t I say that" or "why didn’t I emphasise this word or line instead of that one…"

DP: [laughs] I know exactly what you mean but that’s the beauty of it. In any art form – and writing is as much an art form as music, or fine arts, or painting, or whatever it may be – there is no such thing as perfection.

Perfection is in the eye of the reader or ear of the listener.

As the creator of that art, it’s the constant strive to be better at your craft; but that, I suppose, is what gets people like me and you up every morning – we want to be better; what we have just done may be good but we want to make it even better.

Now, if you were a collector, say a stamp collector, there could be a definite end if you collected every stamp in the world or owned the biggest collection in the world – that’s where you would stop.

In an art from that never ends, no matter what age you are; doesn’t matter if you are in your twenties or in your eighties, you can always improve; that’s the true beauty of it.

RM: To return to Shelter of Bones. I really like the way you opened this album.

Kicking off with the one-two brace of the biting and bristling Soul Parasite and the blues shuffle of Snake Oil City makes for an impacting start, especially as you get those real-world issues and social commentary lyrics in early – the former has an ire-edged vocal decrying two-faced leadership and the agenda of personal gain while the latter offers us further political finger pointing.

DP: I think that, being based in the blues, you have to get away from writing in the women and whisky type clichés.

For the guys that wrote that stuff that was their life – that was their experiences and that’s how they lived.

But for me, that would be a very false kind of world and I think in blues now, or any music genre, really, you have an opportunity to express yourself lyrically.

I saw Soul Parasite and Snake Oil City as platforms for a bit of social commentary on how I feel about certain things, like personal gain and leadership around the world; Snake Oil City was more specifically aimed at the South African Government at the moment.

And as I joke about, when talking about Snake Oil City, if you’re looking for content to write about, especially in a blues kind of vein where you want to have a moan about something, South Africa seems to be a bottomless pit of inspiration at this point, it really does.

It’s a beautiful country with the most amazing people and population but… well, you know as well as I do it’s now worldwide where politicians are taking the piss on certain things and lining their own pockets.

I just felt very strongly about that and believe if you feel very passionate about a subject or certain things, then that’s the right thing to write about and put into song.

I really tried hard on this album to write about stuff that was truly meaningful to me, stuff I cared about and, yes, just have a fat moan about it! [laughs]

But I really wanted stuff that hit home for me; those two songs in particular are very much that.

RM: Machiavellian politics and ever-shifting agendas are as much a pandemic as Covid-19; that’s the sad reality. I fully take your point about South Africa but there are many of us in the UK nodding in agreement and thinking yep; I know exactly where you are coming from – it’s a horrible thing to say but this is, in so many ways, a very unpleasant world right now.

DP: It is man, it really is, without a doubt.

RM: Which leads to the observation that the most famous and oft-used phrase in blues, woke up this morning, has probably never been more relevant or prevalent, but for all the wrong reasons – [phrases in a blues style] woke up this morning, saw the news and went straight back to bed…

DP: [laughs] Yeah, it literally is a bottomless pit of song lyric inspiration; it’s a field day for that sort of thing right now.

RM: Yes, there's a lot of people out there with a bad streak in them...

Perfection is in the eye of the reader or ear of the listener.

As the creator of that art, it’s the constant strive to be better at your craft; but that, I suppose, is what gets people like me and you up every morning – we want to be better; what we have just done may be good but we want to make it even better.

Now, if you were a collector, say a stamp collector, there could be a definite end if you collected every stamp in the world or owned the biggest collection in the world – that’s where you would stop.

In an art from that never ends, no matter what age you are; doesn’t matter if you are in your twenties or in your eighties, you can always improve; that’s the true beauty of it.

RM: To return to Shelter of Bones. I really like the way you opened this album.

Kicking off with the one-two brace of the biting and bristling Soul Parasite and the blues shuffle of Snake Oil City makes for an impacting start, especially as you get those real-world issues and social commentary lyrics in early – the former has an ire-edged vocal decrying two-faced leadership and the agenda of personal gain while the latter offers us further political finger pointing.

DP: I think that, being based in the blues, you have to get away from writing in the women and whisky type clichés.

For the guys that wrote that stuff that was their life – that was their experiences and that’s how they lived.

But for me, that would be a very false kind of world and I think in blues now, or any music genre, really, you have an opportunity to express yourself lyrically.

I saw Soul Parasite and Snake Oil City as platforms for a bit of social commentary on how I feel about certain things, like personal gain and leadership around the world; Snake Oil City was more specifically aimed at the South African Government at the moment.

And as I joke about, when talking about Snake Oil City, if you’re looking for content to write about, especially in a blues kind of vein where you want to have a moan about something, South Africa seems to be a bottomless pit of inspiration at this point, it really does.

It’s a beautiful country with the most amazing people and population but… well, you know as well as I do it’s now worldwide where politicians are taking the piss on certain things and lining their own pockets.

I just felt very strongly about that and believe if you feel very passionate about a subject or certain things, then that’s the right thing to write about and put into song.

I really tried hard on this album to write about stuff that was truly meaningful to me, stuff I cared about and, yes, just have a fat moan about it! [laughs]

But I really wanted stuff that hit home for me; those two songs in particular are very much that.

RM: Machiavellian politics and ever-shifting agendas are as much a pandemic as Covid-19; that’s the sad reality. I fully take your point about South Africa but there are many of us in the UK nodding in agreement and thinking yep; I know exactly where you are coming from – it’s a horrible thing to say but this is, in so many ways, a very unpleasant world right now.

DP: It is man, it really is, without a doubt.

RM: Which leads to the observation that the most famous and oft-used phrase in blues, woke up this morning, has probably never been more relevant or prevalent, but for all the wrong reasons – [phrases in a blues style] woke up this morning, saw the news and went straight back to bed…

DP: [laughs] Yeah, it literally is a bottomless pit of song lyric inspiration; it’s a field day for that sort of thing right now.

RM: Yes, there's a lot of people out there with a bad streak in them...

RM: I'd like to chat a little about the lighter and spacious shades we touched on earlier.

Lost is a beautifully emotive number and one that holds deeper, personal meaning, yet has the ability to resonate with, and touch, any of us who have lived – and lived is the operative word – through worrying or unknown times for our nearest and dearest; in my case my wife who had a serious health scare four years ago.

DP: You just hit the nail on the head again because that’s exactly it; the worry and the not knowing.

It was the same with my wife; as I mention in the introduction of that live performamce, it turned out to a bacterial infection in her stomach, which a course of anti-biotics sorted right out, but it was those weeks and weeks of not knowing that puts you in the darkest, deepest place you’ve ever been; so you start thinking the worst.

The only good thing that comes out of that I guess is that you might be able to write a decent song with those emotions. Fortunately, it all turned out great but it was a very trying time; it really was.

And because it was one of the most trying times of my life so far, as well as for my wife and our kids, I thought this has to be put onto the album; it’s one of my truest and most honest expressions through songwriting and without doubt the most personal track I’ve ever recorded and released.

With a song like that you’re letting go and telling people about your personal life; but that’s cool, y’know?

I suppose the older we get the more we say screw it [laughs], here it is; it happened to me, I’m telling you the story and hopefully it resonates with other people, like it did with you.

RM: Similarly, you are lyrically very honest with I’ll Keep Trying, which carries a looking-in-the-mirror honesty about it. Strong as the lyric is I have to say I think your guitar playing, and phrasing, makes an even bigger statement; it’s gorgeously Knopfler-esque in places.

DP: Thank you man. Once again, to touch upon a point you mentioned earlier, that song is very much like a slightly altered, slow minor blues. That’s my favourite world to express through on the guitar, it really is, so that song came quite naturally when it came to recording the guitar parts.

Lyrically it’s as you say, about taking a good long look in the mirror, more than anything. It’s a tip of the hat to being able to say yeah, I’m well aware of my personal downfalls and it’s something I’m trying to improve on.

Musically I always feel that when you play a guitar solo, what you play in that solo has to serve the song; it can’t just be the guitar player thing where you just say "right, I’m going to play as fast and aggressive as I can for the duration of this solo!" [laughs]

That might be impressive to other guitar players but the message of I’ll Keep Trying is heartfelt and more subtle; I felt the solo had to reflect that message and pay homage to it.

Lost is a beautifully emotive number and one that holds deeper, personal meaning, yet has the ability to resonate with, and touch, any of us who have lived – and lived is the operative word – through worrying or unknown times for our nearest and dearest; in my case my wife who had a serious health scare four years ago.

DP: You just hit the nail on the head again because that’s exactly it; the worry and the not knowing.

It was the same with my wife; as I mention in the introduction of that live performamce, it turned out to a bacterial infection in her stomach, which a course of anti-biotics sorted right out, but it was those weeks and weeks of not knowing that puts you in the darkest, deepest place you’ve ever been; so you start thinking the worst.

The only good thing that comes out of that I guess is that you might be able to write a decent song with those emotions. Fortunately, it all turned out great but it was a very trying time; it really was.

And because it was one of the most trying times of my life so far, as well as for my wife and our kids, I thought this has to be put onto the album; it’s one of my truest and most honest expressions through songwriting and without doubt the most personal track I’ve ever recorded and released.

With a song like that you’re letting go and telling people about your personal life; but that’s cool, y’know?

I suppose the older we get the more we say screw it [laughs], here it is; it happened to me, I’m telling you the story and hopefully it resonates with other people, like it did with you.

RM: Similarly, you are lyrically very honest with I’ll Keep Trying, which carries a looking-in-the-mirror honesty about it. Strong as the lyric is I have to say I think your guitar playing, and phrasing, makes an even bigger statement; it’s gorgeously Knopfler-esque in places.

DP: Thank you man. Once again, to touch upon a point you mentioned earlier, that song is very much like a slightly altered, slow minor blues. That’s my favourite world to express through on the guitar, it really is, so that song came quite naturally when it came to recording the guitar parts.

Lyrically it’s as you say, about taking a good long look in the mirror, more than anything. It’s a tip of the hat to being able to say yeah, I’m well aware of my personal downfalls and it’s something I’m trying to improve on.

Musically I always feel that when you play a guitar solo, what you play in that solo has to serve the song; it can’t just be the guitar player thing where you just say "right, I’m going to play as fast and aggressive as I can for the duration of this solo!" [laughs]

That might be impressive to other guitar players but the message of I’ll Keep Trying is heartfelt and more subtle; I felt the solo had to reflect that message and pay homage to it.

RM: The title track, which closes out the album, adds another colour to the Dan Patlansky sonic palate.

Shelter Of Bones moves from simple yet highly effective heart-beat percussion to a spacious and atmospheric arrangement, before building to, again, another emotive slow blues – but one with a wholly contemporary twist.

I don’t have kids so while I can’t relate to the parental shelter before having to watch them make their own way in an uncertain world, I can fully appreciate the larger concept of where are we going, and what are we leaving, for the children and the next generation.

DP: That's exactly why I decided to call the album Shelter Of Bones, because out of all the concerns I have, and all the stuff I write about, it’s really all about having two young kids.

They are small at the moment so we look after them, we have fun with them, we look over to see what they're getting up to [laughs], but one of my biggest concerns is when the time comes for them to go off and do their own thing. That for me is one of the scariest things I can think of!

Now I’m sure it’s the same for you, in the sense that when we were young the world was a different place; we had freedom and we also had safety; it was a different world!

But the thought of my kids getting to that stage when they are going out with friends, and doing their own thing? I shudder to think what the world might be like then.

That’s pretty much what that song is about – in fact it’s almost like saying if I kicked the bucket tomorrow then this is my message, and advice, to my children.

It also reflects just about every other track on Shelter Of Bones because, for the most part, this album is a reflection of the craziness we’re living in right now; that’s why I felt it was a very fitting title for the album.

RM: I’d also add that it’s the perfect album closer. A recording artist and everyone from manager to label guy to producer and advisor and all the rest, can go round in circles about track sequencing, but every so often there’s that one song that has to be the impact opener or has to be the closing piece.

Shelter Of Bones couldn’t not be the closing statement.

DP: I’m so glad you agree, because when I was looking at a running order for the album that was my feeling too – how can we not close the album with this song? So, yeah, absolutely.

RM: I’d also add that, given the long and constantly revisiting gestation period, the personal aspect, what was going on at the time it was recorded, you’ll look back at this album in the years and decades to come as one of your most important albums as an artist. I truly believe that.

DP: I really appreciate you saying that; I really do. I know every artist in the world says "yeah, I think my best work is my last album" [laughs], which is natural, but I really do feel this album is in the direction I kind of want to head, musically.

I was in a management situation back in South Africa that was, to be honest with you, quite controlling.

When I say controlling, I mean in a creative sense – "you can’t put that song on the album" or "you should write something more like this song;" that kinda thing.

For me that was a very tough thing to write with and to work with, because in the back of your mind you are always thinking "well, management is not going to enjoy this song so I’ll just scrap it."

Whereas with this album, I just thought you know what? I’m going to run the risk of making an album that maybe no-one will like, or maybe only I like, but I’m going to go for it.

I was going to try my best to make an album as close as I could to the album that I wanted to make; I had no other people stopping me from doing that. That was a very liberating feeling...

Shelter Of Bones moves from simple yet highly effective heart-beat percussion to a spacious and atmospheric arrangement, before building to, again, another emotive slow blues – but one with a wholly contemporary twist.

I don’t have kids so while I can’t relate to the parental shelter before having to watch them make their own way in an uncertain world, I can fully appreciate the larger concept of where are we going, and what are we leaving, for the children and the next generation.

DP: That's exactly why I decided to call the album Shelter Of Bones, because out of all the concerns I have, and all the stuff I write about, it’s really all about having two young kids.

They are small at the moment so we look after them, we have fun with them, we look over to see what they're getting up to [laughs], but one of my biggest concerns is when the time comes for them to go off and do their own thing. That for me is one of the scariest things I can think of!

Now I’m sure it’s the same for you, in the sense that when we were young the world was a different place; we had freedom and we also had safety; it was a different world!

But the thought of my kids getting to that stage when they are going out with friends, and doing their own thing? I shudder to think what the world might be like then.

That’s pretty much what that song is about – in fact it’s almost like saying if I kicked the bucket tomorrow then this is my message, and advice, to my children.

It also reflects just about every other track on Shelter Of Bones because, for the most part, this album is a reflection of the craziness we’re living in right now; that’s why I felt it was a very fitting title for the album.

RM: I’d also add that it’s the perfect album closer. A recording artist and everyone from manager to label guy to producer and advisor and all the rest, can go round in circles about track sequencing, but every so often there’s that one song that has to be the impact opener or has to be the closing piece.

Shelter Of Bones couldn’t not be the closing statement.

DP: I’m so glad you agree, because when I was looking at a running order for the album that was my feeling too – how can we not close the album with this song? So, yeah, absolutely.

RM: I’d also add that, given the long and constantly revisiting gestation period, the personal aspect, what was going on at the time it was recorded, you’ll look back at this album in the years and decades to come as one of your most important albums as an artist. I truly believe that.

DP: I really appreciate you saying that; I really do. I know every artist in the world says "yeah, I think my best work is my last album" [laughs], which is natural, but I really do feel this album is in the direction I kind of want to head, musically.

I was in a management situation back in South Africa that was, to be honest with you, quite controlling.

When I say controlling, I mean in a creative sense – "you can’t put that song on the album" or "you should write something more like this song;" that kinda thing.

For me that was a very tough thing to write with and to work with, because in the back of your mind you are always thinking "well, management is not going to enjoy this song so I’ll just scrap it."

Whereas with this album, I just thought you know what? I’m going to run the risk of making an album that maybe no-one will like, or maybe only I like, but I’m going to go for it.

I was going to try my best to make an album as close as I could to the album that I wanted to make; I had no other people stopping me from doing that. That was a very liberating feeling...

RM: Your management issues as just described make me recall vividly our very first conversation some years ago when we discussed your earliest albums; we both agreed that the Dan Patlansky musical story more accurately starts with the perfectly titled third album, Real.

The two albums before Real sound like producer led albums, or someone else’s idea of how you should sound.

DP: Exactly, those first two albums weren’t me at all. But you mature, grow a set of balls and eventually you’re able to say "I don’t like that and I do not want that type of thing on the album."

But when you’re a young artist, you’re wide eyed and bushy tailed; you’re thinking "well, this producer said this is the way I should do it" so you just follow.

But that’s not always the greatest choice I think, and it can hurt you.

But I learnt a lot from those albums – I definitely don’t listen to them any more though [laughs] and I cringe when people talk about them, but it is what it is. From there it was onward and upward.

RM: And now its onward and upward in the company of a new Fender Strat.

Again, when we first spoke, we talked about The Beast, which had the neck of your beloved Old Red fitted to it, but it was getting close to retirement…

DP: That’s exactly right and it’s a great story.

I put that Beast guitar together from a hybrid of what was pretty much my favourite parts of my other guitars.

But, when I flew in to Hamburg to start a tour a few years ago, I didn’t realise that the wood in the neck of that guitar, which was pre-1965, was made from Brazilian Rosewood, which is like ivory in the world of wood!

You actually need documentation and permits for it, which I couldn’t get – so they nearly confiscated it!

So now I realise "well, I can’t tour with this anymore," plus the guitar was getting older and older and becoming more and more unplayable.

So I commissioned one of the Master Builders at Fender over in California to make me an exact replica of The Beast, with all the different parts but in a different colour, to distinguish it from the original.

It took three years to build, which was a long process and a long wait [laughs], but I got it in 2019, just before lockdown.

And I have to be honest with you Ross, it’s by far the best guitar I’ve played to date; it’s an unbelievable instrument and an exact replica! I really feel blessed to own this thing – it was definitely worth the wait!

RM: I’m so pleased for you, because I know how much you loved The Beast and how much of a Strat man you are. You've clearly found your perfect partner with the Masterbuilt replica.

DP: Yeah, this is the one! And because it’s essentially new, even though it’s a copy of my older guitar, this one will be with me for the next twenty to thirty years. It’s great to be able to know that in the back of your mind and to know, as you’ve just said, that you’ve found your perfect partner!

RM: I'm also delighted to be able to report that, having seen them in your studio, you've given your faithful, retired guitars pride of place on your wall…

DP: I have! I’ve got The Beast and Old Red hanging up on the wall of my home studio, so I can look at them and appreciate their beauty. When I’m home and not touring I stare up at them every day of my life!

So many hours and so many tours playing them, and so much blood and sweat has gone into them, that they are pretty much unplayable at this point – in fact they are completely knackered [laughs], which is sad, but they invoke a lot of memories of particular shows and particulars tours, so they are active in that sense.

They were great guitars and served me incredibly well.

RM: Absolutely. They were with you from those earliest South African club shows to your larger recognition and emergence in the UK and European blues rock scenes. They will always be part of you.

DP: Exactly! They are like your best friend on the road; that one commonality when you’re touring because being on the road is crazy; it’s different every night with different cities, different venues, different hotels… but the one thing in common is that guitar!

RM: I'd like to end by coming back to the present and the fact that on this tour you are promoting and working with the wonderful Nordoff and Robbins Music Therapy Charity. How did that come about?

DP: Well, first of all, I always feel like it’s great to be able to give back in life, and that can be through donations, or having charities on board, so you can support them.

Now this charity in particular, which was suggested by Glenn Sargeant, who is doing PR for me on this tour, pushed the right buttons for me, given what they do.

I’m not overly familiar with all the charities in the UK but as soon as I read what Nordoff and Robbins were all about – and they do fantastic stuff – I said to Glenn "this makes a world of sense to be on board with them; this is such a really good match between artist and charity."

So we’re helping the charity in any way we can and by having their representatives at the shows and the merch stands, and spreading the word about what they do.

It's just such a really good thing to be doing; I’m a firm believer in Karma.

RM: Oh you’re paying back in dividends here Dan, trust me.

I've helped support Nordoff and Robbins in the past so I hope you – and those that will be reading this article – will indulge me as I repeat a story that was relayed to me at a Nordoff and Robbins charity show I was part of a few years ago...

Hannah was a then five year old girl who didn’t have autism but had a genetic disorder that made it hard for her to ever make eye contact or be directly communicative with anyone, even her parents.

Nothing really worked until trying music therapy via Nordoff and Robbins.

A therapy-music teacher taught Hannah the learning song The Wheels on the Bus, of which the first verse is simply [sings] "The wheels on the bus go round and round," with repeats of "round and round" and ending on "all day long."

Hannah seemed attentive and understanding of the song, so she was asked if she’d like to sing it back.

She then – completely unprompted – sang her own words back about her day, meeting her teacher, what she had for lunch… her day, in song.

DP: No. Way. That’s absolutely amazing!

RM: Isn’t it? Something in the music, or the melody, or the rhythmic cadence, triggered that reaction.

Better yet was when Hannah’s mother said to me "my favourite period of life is that one hour on a Friday when Hannah goes to music therapy."

DP: Wow. That story, besides being mind-blowing, makes me think back to when I was young.

I might never have had any sort of disability but music did a very similar thing for me when I was a kid, and maybe you, and many others, too – those times when you were unsettled, or maybe you were a little bit outside of what the other kids were doing.

Music was always the thing that zoned me out and produced that level of calmness, from when I was a kid through to being a young teenager.

So I can believe the effect it had on Hannah completely; music is such a powerful thing. That’s why I’m not worried by all the talk of A.I. taking over the music industry because human beings will always want other human beings, including through music. It’s a powerful thing, it’s a powerful connection.

RM: Indeed it is. In summation, and as a sign-off to that story about Hannah I’d say this.

For you and me, Dan, and other musicians, and music fans, music enriches our lives immeasurably.

But if you take that importance of music in our lives to the next level of a dependency in music, which doubles or even triples that initial importance? That’s Nordoff and Robbins.

DP: And that’s exactly why that charity was the obvious choice for this tour – it's something I really believe in, and understand. I can’t do what Nordoff and Robbins, and all the teachers and the therapists do, but I am in awe of people like that and how they use such a powerful medium as music to help and heal people, and change lives.

RM: I cannot think of better way, or a more positive message, on which to end.

Thanks so much for talking at length again to FabricationsHQ, Dan; always such a pleasure.

DP: Thank you very much my brother, it's always great to catch up and this has been fantastic, and so cool. I’ve enjoyed every minute of it. I'll see everyone out on the road!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Dan Patlansky

April 2023

Photo credits: Tobias Johan Coetsee

Tickets for all upcoming UK & European shows are on sale now at https://danpatlansky.com/tour-dates/

Nordoff and Robbins Music Therapy charity: https://www.nordoff-robbins.org.uk/

Donate here: https://www.nordoff-robbins.org.uk/donate/

The two albums before Real sound like producer led albums, or someone else’s idea of how you should sound.

DP: Exactly, those first two albums weren’t me at all. But you mature, grow a set of balls and eventually you’re able to say "I don’t like that and I do not want that type of thing on the album."

But when you’re a young artist, you’re wide eyed and bushy tailed; you’re thinking "well, this producer said this is the way I should do it" so you just follow.

But that’s not always the greatest choice I think, and it can hurt you.

But I learnt a lot from those albums – I definitely don’t listen to them any more though [laughs] and I cringe when people talk about them, but it is what it is. From there it was onward and upward.

RM: And now its onward and upward in the company of a new Fender Strat.

Again, when we first spoke, we talked about The Beast, which had the neck of your beloved Old Red fitted to it, but it was getting close to retirement…

DP: That’s exactly right and it’s a great story.

I put that Beast guitar together from a hybrid of what was pretty much my favourite parts of my other guitars.

But, when I flew in to Hamburg to start a tour a few years ago, I didn’t realise that the wood in the neck of that guitar, which was pre-1965, was made from Brazilian Rosewood, which is like ivory in the world of wood!

You actually need documentation and permits for it, which I couldn’t get – so they nearly confiscated it!

So now I realise "well, I can’t tour with this anymore," plus the guitar was getting older and older and becoming more and more unplayable.

So I commissioned one of the Master Builders at Fender over in California to make me an exact replica of The Beast, with all the different parts but in a different colour, to distinguish it from the original.

It took three years to build, which was a long process and a long wait [laughs], but I got it in 2019, just before lockdown.

And I have to be honest with you Ross, it’s by far the best guitar I’ve played to date; it’s an unbelievable instrument and an exact replica! I really feel blessed to own this thing – it was definitely worth the wait!

RM: I’m so pleased for you, because I know how much you loved The Beast and how much of a Strat man you are. You've clearly found your perfect partner with the Masterbuilt replica.

DP: Yeah, this is the one! And because it’s essentially new, even though it’s a copy of my older guitar, this one will be with me for the next twenty to thirty years. It’s great to be able to know that in the back of your mind and to know, as you’ve just said, that you’ve found your perfect partner!

RM: I'm also delighted to be able to report that, having seen them in your studio, you've given your faithful, retired guitars pride of place on your wall…

DP: I have! I’ve got The Beast and Old Red hanging up on the wall of my home studio, so I can look at them and appreciate their beauty. When I’m home and not touring I stare up at them every day of my life!

So many hours and so many tours playing them, and so much blood and sweat has gone into them, that they are pretty much unplayable at this point – in fact they are completely knackered [laughs], which is sad, but they invoke a lot of memories of particular shows and particulars tours, so they are active in that sense.

They were great guitars and served me incredibly well.

RM: Absolutely. They were with you from those earliest South African club shows to your larger recognition and emergence in the UK and European blues rock scenes. They will always be part of you.

DP: Exactly! They are like your best friend on the road; that one commonality when you’re touring because being on the road is crazy; it’s different every night with different cities, different venues, different hotels… but the one thing in common is that guitar!

RM: I'd like to end by coming back to the present and the fact that on this tour you are promoting and working with the wonderful Nordoff and Robbins Music Therapy Charity. How did that come about?

DP: Well, first of all, I always feel like it’s great to be able to give back in life, and that can be through donations, or having charities on board, so you can support them.

Now this charity in particular, which was suggested by Glenn Sargeant, who is doing PR for me on this tour, pushed the right buttons for me, given what they do.

I’m not overly familiar with all the charities in the UK but as soon as I read what Nordoff and Robbins were all about – and they do fantastic stuff – I said to Glenn "this makes a world of sense to be on board with them; this is such a really good match between artist and charity."

So we’re helping the charity in any way we can and by having their representatives at the shows and the merch stands, and spreading the word about what they do.

It's just such a really good thing to be doing; I’m a firm believer in Karma.

RM: Oh you’re paying back in dividends here Dan, trust me.

I've helped support Nordoff and Robbins in the past so I hope you – and those that will be reading this article – will indulge me as I repeat a story that was relayed to me at a Nordoff and Robbins charity show I was part of a few years ago...

Hannah was a then five year old girl who didn’t have autism but had a genetic disorder that made it hard for her to ever make eye contact or be directly communicative with anyone, even her parents.

Nothing really worked until trying music therapy via Nordoff and Robbins.

A therapy-music teacher taught Hannah the learning song The Wheels on the Bus, of which the first verse is simply [sings] "The wheels on the bus go round and round," with repeats of "round and round" and ending on "all day long."

Hannah seemed attentive and understanding of the song, so she was asked if she’d like to sing it back.

She then – completely unprompted – sang her own words back about her day, meeting her teacher, what she had for lunch… her day, in song.

DP: No. Way. That’s absolutely amazing!

RM: Isn’t it? Something in the music, or the melody, or the rhythmic cadence, triggered that reaction.

Better yet was when Hannah’s mother said to me "my favourite period of life is that one hour on a Friday when Hannah goes to music therapy."

DP: Wow. That story, besides being mind-blowing, makes me think back to when I was young.

I might never have had any sort of disability but music did a very similar thing for me when I was a kid, and maybe you, and many others, too – those times when you were unsettled, or maybe you were a little bit outside of what the other kids were doing.

Music was always the thing that zoned me out and produced that level of calmness, from when I was a kid through to being a young teenager.

So I can believe the effect it had on Hannah completely; music is such a powerful thing. That’s why I’m not worried by all the talk of A.I. taking over the music industry because human beings will always want other human beings, including through music. It’s a powerful thing, it’s a powerful connection.

RM: Indeed it is. In summation, and as a sign-off to that story about Hannah I’d say this.

For you and me, Dan, and other musicians, and music fans, music enriches our lives immeasurably.

But if you take that importance of music in our lives to the next level of a dependency in music, which doubles or even triples that initial importance? That’s Nordoff and Robbins.

DP: And that’s exactly why that charity was the obvious choice for this tour – it's something I really believe in, and understand. I can’t do what Nordoff and Robbins, and all the teachers and the therapists do, but I am in awe of people like that and how they use such a powerful medium as music to help and heal people, and change lives.

RM: I cannot think of better way, or a more positive message, on which to end.

Thanks so much for talking at length again to FabricationsHQ, Dan; always such a pleasure.

DP: Thank you very much my brother, it's always great to catch up and this has been fantastic, and so cool. I’ve enjoyed every minute of it. I'll see everyone out on the road!

Ross Muir

Muirsical Conversation with Dan Patlansky

April 2023

Photo credits: Tobias Johan Coetsee

Tickets for all upcoming UK & European shows are on sale now at https://danpatlansky.com/tour-dates/

Nordoff and Robbins Music Therapy charity: https://www.nordoff-robbins.org.uk/

Donate here: https://www.nordoff-robbins.org.uk/donate/