The stray blues cat

Muirsical Conversation with Del Bromham

Muirsical Conversation with Del Bromham

Del Bromham will always be best known as the guitarist and primary songwriter of London based 70s rock band Stray, cited by many a fan and music critic as the greatest little rock act never to make it big.

However with the resurgence in classic rock and the benefit of musical hindsight, Stray’s place in British rock and roll has since been acknowledged and firmly established.

Esoteric Recordings recent all-encompassing and comprehensive anthologies covering Stray's original 1970 to 1977 run reinforce and reconfirm the band’s quality, and standing.

But Del Bromham, who is at the helm of the 21st century Stray, is also an ever-gigging blues rock performer (with Del Bromham’s Blues Devils) and solo recording artist.

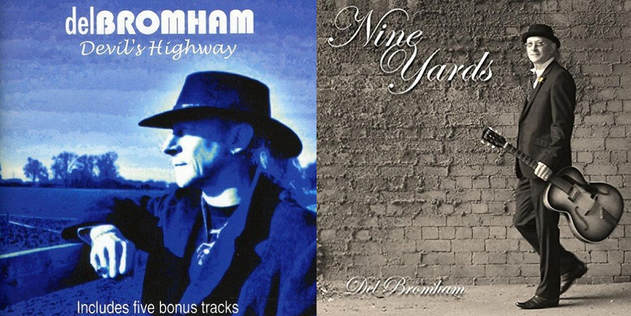

Blues album Devil’s Highway and the mix of acoustic blues and Stray styled rock that shaped Nine Yards were acclaimed releases but latest offering, White Feather, is Del Bromham's best, and most personal work, to date. It’s also the well respected musician's most eclectic, incorporating rock, pop, blues and soul.

Just prior to the release White Feather Del Bromham spoke with FabricationsHQ in an extended life and times conversation that covered Stray’s beginnings and four young lads who wanted to be little different, his later blues-based and solo excursions and the reasoning behind the personal nature of White Feather, its title, the various song styles found within and the life experiences lyricism.

Ross Muir: The recent Stray anthologies from Esoteric Recordings, All in Your Mind 1970-1974 and Fire & Glass 1975-1977, are excellent, all encompassing sets that catalogue just who good a band Stray were, as well as how different and musically diverse, in comparison to the majority of seventies rock bands.

As the band’s guitarist and primary songwriter Stray are part of your musical DNA but can you detach yourself, step aside, look at Stray from the outside and think "that was a bloody good little band."

Del Bromham: I have to be honest and say yeah, I probably can. We were always pretty sure of ourselves and always thought we were different to other bands, but I think that’s also because of our then youth.

But, also, with that youth and like most kids of our age, we had our little insecurities – I don’t think we ever thought we were good enough, musically.

RM: That really surprises me because there was no lack of confidence or ability on stage or in what you tried, and came up with, in the studio…

DB: Well, with Stray we never had any musical barriers; we would just attempt anything as it came to us – it might be jazzy, it might be rocky, it might be folky or soulful, we didn’t really have a plan at all!

But I think it was more a case of we always thought we could do better.

But to go back to your original question I do believe it was a really good band, and I think if we had everything going for us at the time, especially in those early years and the first three or four albums, it might have been different.

We were also in that era where certain elements of the audience, whether they be male or female, latched on to certain members of the band, for whatever reason – "I really like the singer" or "oh I love the guitarist" [laughs], so we had a fan base.

That package – guitarist, bassist, drummer, singer – was also quite a commercial package, but unfortunately we never really had what it took, be it luck, the right management, or whatever other reason you can come up with, to get us to that next level.

However with the resurgence in classic rock and the benefit of musical hindsight, Stray’s place in British rock and roll has since been acknowledged and firmly established.

Esoteric Recordings recent all-encompassing and comprehensive anthologies covering Stray's original 1970 to 1977 run reinforce and reconfirm the band’s quality, and standing.

But Del Bromham, who is at the helm of the 21st century Stray, is also an ever-gigging blues rock performer (with Del Bromham’s Blues Devils) and solo recording artist.

Blues album Devil’s Highway and the mix of acoustic blues and Stray styled rock that shaped Nine Yards were acclaimed releases but latest offering, White Feather, is Del Bromham's best, and most personal work, to date. It’s also the well respected musician's most eclectic, incorporating rock, pop, blues and soul.

Just prior to the release White Feather Del Bromham spoke with FabricationsHQ in an extended life and times conversation that covered Stray’s beginnings and four young lads who wanted to be little different, his later blues-based and solo excursions and the reasoning behind the personal nature of White Feather, its title, the various song styles found within and the life experiences lyricism.

Ross Muir: The recent Stray anthologies from Esoteric Recordings, All in Your Mind 1970-1974 and Fire & Glass 1975-1977, are excellent, all encompassing sets that catalogue just who good a band Stray were, as well as how different and musically diverse, in comparison to the majority of seventies rock bands.

As the band’s guitarist and primary songwriter Stray are part of your musical DNA but can you detach yourself, step aside, look at Stray from the outside and think "that was a bloody good little band."

Del Bromham: I have to be honest and say yeah, I probably can. We were always pretty sure of ourselves and always thought we were different to other bands, but I think that’s also because of our then youth.

But, also, with that youth and like most kids of our age, we had our little insecurities – I don’t think we ever thought we were good enough, musically.

RM: That really surprises me because there was no lack of confidence or ability on stage or in what you tried, and came up with, in the studio…

DB: Well, with Stray we never had any musical barriers; we would just attempt anything as it came to us – it might be jazzy, it might be rocky, it might be folky or soulful, we didn’t really have a plan at all!

But I think it was more a case of we always thought we could do better.

But to go back to your original question I do believe it was a really good band, and I think if we had everything going for us at the time, especially in those early years and the first three or four albums, it might have been different.

We were also in that era where certain elements of the audience, whether they be male or female, latched on to certain members of the band, for whatever reason – "I really like the singer" or "oh I love the guitarist" [laughs], so we had a fan base.

That package – guitarist, bassist, drummer, singer – was also quite a commercial package, but unfortunately we never really had what it took, be it luck, the right management, or whatever other reason you can come up with, to get us to that next level.

RM: For me, and many fans and critics, Stray can legitimately lay claim to being the greatest little rock band of the 70s never to make it big. There was also a clear camaraderie and chemistry – one for all and all for one, whether with original lead vocalist Steve Gadd or with Pete Dyer, when he came in.

You were a true people’s band.

DB: That was often heard back then. The fans and audiences associated with us and we were a peoples band. I don’t think we ever had any airs and graces; when we did a gig the audience were part of the band because we were all in it together – not that there was ever more of us than the four guys on the stage of course!

We also only ever had three or four roadies with us through our entire career; we were one big happy family.

You probably saw that very rare video of Stray on German TV on my Facebook page a few months ago? Someone mentioned how happy we looked on that video – that’s because we were happy, we were really enjoying ourselves!

All the other names around that time, they had to look serious, they had to be serious musicians; we were just four young lads who considered ourselves very lucky to be able to do what we enjoyed doing.

Before we even had a band Steve Gadd, Gary Giles and myself knew each other; since we were eleven years old in fact and heading to the same secondary school. We had all come from different primary schools but when we met, between the three of us, something just clicked right away.

It wasn’t until a few years later, when we were fifteen years old, we thought about forming a band; we decided that we were going to do it properly but that we were also going to have fun with it and the music we were covering at the time. Then, gradually, we integrated our own songs in to what we were doing.

RM: And these would primarily be your songs?

DB: Yeah, I was writing songs as soon as I could play a guitar; I was writing my first songs when I was about eleven or twelve years old.

So some of those Stray songs had always been there and I was trying to make them commercial, fitting in with the sixties chart songs we were playing at the time – Beatles, The Hollies, Rolling Stones.

As a songwriter I’ve always been a verses and choruses man – and melody of course, got to catch them with a melody – we always hoped we would be able to write and play songs people could connect with.

Lyrically I’ve obviously developed a lot more over the years as you gain life experiences but when you’re younger you are making up stories, or writing about stuff that’s based on other stuff you have heard [laughs].

As I’ve got older I’ve written more and more about personal or life experiences but all my writing life I’ve tried to write songs that people will either be interested in or can connect with, on a personal level.

RM: Those comments about melody, your lyricism and storytelling allows me to jump across the decades to more recent times and your new album, White Feather.

Your previous solo album Nine Yards was a great mix of contemporary blues rock and a couple of numbers that were clearly personal but White Feather is even more personal and very diverse musically.

There are songs on White Feather that could, and should, be playlisted for BBC Radio 2…

DB: Real-life stories are the core of the twelve songs on White Feather, a number of which are quite personal, relating to my eldest daughter Zoe, who passed away in 2016.

Now, I’m a pretty ordinary kind of guy, one who doesn’t necessarily believe in superstitions or those who say certain things happen when someone close dies but, without going in to too much detail, when my daughter passed I had a couple of very strange things happen to me.

The most noticeable, and the ones that are stuck forever in my mind – to the degree that I wrote a song about it – were two instances where a white feather floated down in front of me yet there was no sign of a bird anywhere. That made me recall that other people have had those sorts of experiences and the title song of the album developed from there...

You were a true people’s band.

DB: That was often heard back then. The fans and audiences associated with us and we were a peoples band. I don’t think we ever had any airs and graces; when we did a gig the audience were part of the band because we were all in it together – not that there was ever more of us than the four guys on the stage of course!

We also only ever had three or four roadies with us through our entire career; we were one big happy family.

You probably saw that very rare video of Stray on German TV on my Facebook page a few months ago? Someone mentioned how happy we looked on that video – that’s because we were happy, we were really enjoying ourselves!

All the other names around that time, they had to look serious, they had to be serious musicians; we were just four young lads who considered ourselves very lucky to be able to do what we enjoyed doing.

Before we even had a band Steve Gadd, Gary Giles and myself knew each other; since we were eleven years old in fact and heading to the same secondary school. We had all come from different primary schools but when we met, between the three of us, something just clicked right away.

It wasn’t until a few years later, when we were fifteen years old, we thought about forming a band; we decided that we were going to do it properly but that we were also going to have fun with it and the music we were covering at the time. Then, gradually, we integrated our own songs in to what we were doing.

RM: And these would primarily be your songs?

DB: Yeah, I was writing songs as soon as I could play a guitar; I was writing my first songs when I was about eleven or twelve years old.

So some of those Stray songs had always been there and I was trying to make them commercial, fitting in with the sixties chart songs we were playing at the time – Beatles, The Hollies, Rolling Stones.

As a songwriter I’ve always been a verses and choruses man – and melody of course, got to catch them with a melody – we always hoped we would be able to write and play songs people could connect with.

Lyrically I’ve obviously developed a lot more over the years as you gain life experiences but when you’re younger you are making up stories, or writing about stuff that’s based on other stuff you have heard [laughs].

As I’ve got older I’ve written more and more about personal or life experiences but all my writing life I’ve tried to write songs that people will either be interested in or can connect with, on a personal level.

RM: Those comments about melody, your lyricism and storytelling allows me to jump across the decades to more recent times and your new album, White Feather.

Your previous solo album Nine Yards was a great mix of contemporary blues rock and a couple of numbers that were clearly personal but White Feather is even more personal and very diverse musically.

There are songs on White Feather that could, and should, be playlisted for BBC Radio 2…

DB: Real-life stories are the core of the twelve songs on White Feather, a number of which are quite personal, relating to my eldest daughter Zoe, who passed away in 2016.

Now, I’m a pretty ordinary kind of guy, one who doesn’t necessarily believe in superstitions or those who say certain things happen when someone close dies but, without going in to too much detail, when my daughter passed I had a couple of very strange things happen to me.

The most noticeable, and the ones that are stuck forever in my mind – to the degree that I wrote a song about it – were two instances where a white feather floated down in front of me yet there was no sign of a bird anywhere. That made me recall that other people have had those sorts of experiences and the title song of the album developed from there...

RM: White Feather, the song, is a lovely musical epitaph to Zoe.

I have to also say that White Feather, the album, is, for me, your most accomplished work to date as well as the most eclectic, yet still very much Del Bromham across all twelve songs.

DB: Thank you. I have to tell you though that while all twelve songs are new, two of them in actual fact I’ve revisited, although you wouldn’t have heard them before.

One, Life, goes back to about 1967 or 1968 and was one of the first psychedelically themed songs I ever wrote! The band, who back then were called The Stray, played it live when we were about seventeen years old.

We played it on and off, right up to the recording of the first album, but we had a lot of songs by then and a it didn’t make the cut, or even get recorded. But I’ve had that song on the back-burner because I’ve always wanted to revisit it.

When I went in to Echo Studios in Buckingham with that song with my sound and recording engineer, Jamie Masterson, was completely on the same page as me – I’ve said this before about Jamie but for me, after all these years, it was like finding my George Martin!

Jamie was brilliant, he knew exactly what I meant by the song; we both went back to 1968 and kept a little of its psychedelia. Life is definitely a little bit Stray, in their early style.

RM: Isn’t that great, how it’s finally found the perfect home, some fifty years later.

And the other revisited number?

DB: That’s the song called Genevieve; it comes from around 1969.

At the time I was, believe it not, looking to write some Children’s books, but then Stray got signed with Transatlantic Records for the debut album.

There was talk with the label about maybe getting me to do a solo album or finding me a publishing deal for the books because by that time I had written a couple of songs relating to what would have been one of the book stories; the song Genevieve is actually the main character of the book that never was.

I knew I had to put those two songs to bed because I believed in them; with Jamie working with me on both we also managed to create a bit of nostalgia.

RM: Even with that early Stray connection they are both great fits for the multi-style of White Feather; they sit very comfortably on the album.

DB: That’s exactly what I want to achieve with the songwriting; I always hope the songs that I’ve written are going to be around forever, or don’t put you in a particular time zone or era.

The Beatles have most certainly done that with their songs; people will still be singing Hey Jude long after McCartney has gone and I’d like to think people will still be playing some of my songs after I’ve gone.

But for that to happen you have to have that commerciality and catchy appeal; that’s what Stray always tried to achieve, right from the beginning.

Not everyone is going to like your music of course but I always wanted those who do like it to be playing Stray’s music and my music after all these years. That’s the goal; that’s the desire.

RM: It's a goal that's being achieved, primarily because of the strength and diversity of the songs.

Stray’s self-titled debut is still played and revered to this day; similarly appreciated is Suicide, where you introduced keyboards and then Mudanzas, which incorporated strings and brass.

1977’s Houdini fell foul of punk but if it came out now we’d all be banging on about it being one of the best albums of the current blues rock movement.

Albums from later incarnations of the band have also been well received – 1997’s New Dawn for example.

That longevity and legacy comes back to what you said earlier about the songwriting.

DB: I think so, but what’s really interesting about Stray now is that my solo stuff, and live performances as Del Bromham’s Blues Devils, has rejuvenated that interest in Stray; it wasn’t the other way around!

And that, I truly believe, is because of the blues and blues rock movement you mentioned – but I almost got in to that by accident!

To cut a long story short I found that some venues deemed Stray to be too heavy rock, but they accepted me going in there because it was a case of "well, Del will do something a bit more bluesy" [laughs].

But I would always stick a couple of Stray tunes in because I was very aware that some of the people going along to these venues or festivals weren’t particularly any sort of blues aficionados; they were there just to enjoy the music.

In fact it was actually the promoters that were calling some of the shows "blues nights," even although a percentage of the audience weren’t really blues fans; they just wanted to hear good music.

Now, of course, some of those blues festivals have changed their name to rock and blues festivals; they don’t always have artists on the bill that could ever be described as blues artists – Focus, Wishbone Ash, Uriah Heep for example.

RM: So you started to become aware of a crossover audience; the blues fans and the classic rock fans.

DB: Yeah. When I played a blues set, I’d always get people coming up to me after and saying something like "you know Del, I’ve always loved the Mudanzas album" or others might say "I didn’t really like Mudanzas when it first came out, with all the strings and brass" but then they would tell me they had revisited it more lately and now they loved it!

The other side of the coin is the younger fans who are coming along now. They'll say "I love your stuff, my dad used to always play your albums!" or they may have heard about Stray through Iron Maiden recording one of our songs – Steve Harris has mentioned that Stray were a big influence on Maiden, so you get fans of Iron Maiden coming along to see why they cited us as an Influence and buying some of the albums.

So, consequently, there has been a bit of a demand for the Stray albums; Esoteric Recordings did a deal with Universal and put out the two anthology packages. There is definitely more of a demand now for Stray, and my own solo stuff, than there was, say, ten years ago.

RM: And deservedly so; we’re in classic rock resurgence and there’s the blues rock scene we’ve mentioned.

There’s also a softening of the blues purist who balks at anything not twelve-bar or B.B. King; similarly a lot of rock fans are gaining an appreciation for and understanding of the blues, certainly more than would have been the case fifteen years ago.

Your blues album, Devils Highway, is a great case in point. It was originally released in 2004 but did much better business when it was re-released in 2011.

DB: And that album too, was almost by accident! [laughs].

What happened there was I had been doing some acoustic shows; the sets were primarily Stray songs but I was sticking in a few blues tunes I remembered from way back when.

But a couple of people, including my good mate and original Stray roadie Paul Newcomb, said "you should think about doing a blues album." I was always the outsider on that though, because there are artists far more qualified than me to do a blues album!

But then I thought what I should do is make it my take on the blues. I dropped in a few of the blues tunes I remembered from growing up, recorded a few of my own songs which I had written in the style of blues, and recorded some of them acoustically....

I have to also say that White Feather, the album, is, for me, your most accomplished work to date as well as the most eclectic, yet still very much Del Bromham across all twelve songs.

DB: Thank you. I have to tell you though that while all twelve songs are new, two of them in actual fact I’ve revisited, although you wouldn’t have heard them before.

One, Life, goes back to about 1967 or 1968 and was one of the first psychedelically themed songs I ever wrote! The band, who back then were called The Stray, played it live when we were about seventeen years old.

We played it on and off, right up to the recording of the first album, but we had a lot of songs by then and a it didn’t make the cut, or even get recorded. But I’ve had that song on the back-burner because I’ve always wanted to revisit it.

When I went in to Echo Studios in Buckingham with that song with my sound and recording engineer, Jamie Masterson, was completely on the same page as me – I’ve said this before about Jamie but for me, after all these years, it was like finding my George Martin!

Jamie was brilliant, he knew exactly what I meant by the song; we both went back to 1968 and kept a little of its psychedelia. Life is definitely a little bit Stray, in their early style.

RM: Isn’t that great, how it’s finally found the perfect home, some fifty years later.

And the other revisited number?

DB: That’s the song called Genevieve; it comes from around 1969.

At the time I was, believe it not, looking to write some Children’s books, but then Stray got signed with Transatlantic Records for the debut album.

There was talk with the label about maybe getting me to do a solo album or finding me a publishing deal for the books because by that time I had written a couple of songs relating to what would have been one of the book stories; the song Genevieve is actually the main character of the book that never was.

I knew I had to put those two songs to bed because I believed in them; with Jamie working with me on both we also managed to create a bit of nostalgia.

RM: Even with that early Stray connection they are both great fits for the multi-style of White Feather; they sit very comfortably on the album.

DB: That’s exactly what I want to achieve with the songwriting; I always hope the songs that I’ve written are going to be around forever, or don’t put you in a particular time zone or era.

The Beatles have most certainly done that with their songs; people will still be singing Hey Jude long after McCartney has gone and I’d like to think people will still be playing some of my songs after I’ve gone.

But for that to happen you have to have that commerciality and catchy appeal; that’s what Stray always tried to achieve, right from the beginning.

Not everyone is going to like your music of course but I always wanted those who do like it to be playing Stray’s music and my music after all these years. That’s the goal; that’s the desire.

RM: It's a goal that's being achieved, primarily because of the strength and diversity of the songs.

Stray’s self-titled debut is still played and revered to this day; similarly appreciated is Suicide, where you introduced keyboards and then Mudanzas, which incorporated strings and brass.

1977’s Houdini fell foul of punk but if it came out now we’d all be banging on about it being one of the best albums of the current blues rock movement.

Albums from later incarnations of the band have also been well received – 1997’s New Dawn for example.

That longevity and legacy comes back to what you said earlier about the songwriting.

DB: I think so, but what’s really interesting about Stray now is that my solo stuff, and live performances as Del Bromham’s Blues Devils, has rejuvenated that interest in Stray; it wasn’t the other way around!

And that, I truly believe, is because of the blues and blues rock movement you mentioned – but I almost got in to that by accident!

To cut a long story short I found that some venues deemed Stray to be too heavy rock, but they accepted me going in there because it was a case of "well, Del will do something a bit more bluesy" [laughs].

But I would always stick a couple of Stray tunes in because I was very aware that some of the people going along to these venues or festivals weren’t particularly any sort of blues aficionados; they were there just to enjoy the music.

In fact it was actually the promoters that were calling some of the shows "blues nights," even although a percentage of the audience weren’t really blues fans; they just wanted to hear good music.

Now, of course, some of those blues festivals have changed their name to rock and blues festivals; they don’t always have artists on the bill that could ever be described as blues artists – Focus, Wishbone Ash, Uriah Heep for example.

RM: So you started to become aware of a crossover audience; the blues fans and the classic rock fans.

DB: Yeah. When I played a blues set, I’d always get people coming up to me after and saying something like "you know Del, I’ve always loved the Mudanzas album" or others might say "I didn’t really like Mudanzas when it first came out, with all the strings and brass" but then they would tell me they had revisited it more lately and now they loved it!

The other side of the coin is the younger fans who are coming along now. They'll say "I love your stuff, my dad used to always play your albums!" or they may have heard about Stray through Iron Maiden recording one of our songs – Steve Harris has mentioned that Stray were a big influence on Maiden, so you get fans of Iron Maiden coming along to see why they cited us as an Influence and buying some of the albums.

So, consequently, there has been a bit of a demand for the Stray albums; Esoteric Recordings did a deal with Universal and put out the two anthology packages. There is definitely more of a demand now for Stray, and my own solo stuff, than there was, say, ten years ago.

RM: And deservedly so; we’re in classic rock resurgence and there’s the blues rock scene we’ve mentioned.

There’s also a softening of the blues purist who balks at anything not twelve-bar or B.B. King; similarly a lot of rock fans are gaining an appreciation for and understanding of the blues, certainly more than would have been the case fifteen years ago.

Your blues album, Devils Highway, is a great case in point. It was originally released in 2004 but did much better business when it was re-released in 2011.

DB: And that album too, was almost by accident! [laughs].

What happened there was I had been doing some acoustic shows; the sets were primarily Stray songs but I was sticking in a few blues tunes I remembered from way back when.

But a couple of people, including my good mate and original Stray roadie Paul Newcomb, said "you should think about doing a blues album." I was always the outsider on that though, because there are artists far more qualified than me to do a blues album!

But then I thought what I should do is make it my take on the blues. I dropped in a few of the blues tunes I remembered from growing up, recorded a few of my own songs which I had written in the style of blues, and recorded some of them acoustically....

DB: Devils Highway was also, partly, a vehicle for some solo acoustic sets I did back in 2004 when I was asked to accompany Leslie West.

Leslie had his Blues To Die For album out and Paul Newcomb managed to persuade him to come over to the UK to do a tour to promote it. Leslie said "OK, that’s great!" but then started to mention all these people he was going to bring over with him! [laughs].

Paul had to say "no, just come over with your acoustic guitar, tell some stories and play the songs solo."

Leslie said he couldn’t do that until Paul replied "well, Del Bromham does it."

Leslie replied "Del does it? Well, I’ll do it if Del does it with me!" [laughs].

So that’s how that little tour, and album, came about.

The re-release of Devil’s Highway you mentioned came about when I was doing the next album, Nine Yards. On the strength of the popularity of that one Angel Air Records decided to re-release Devil’s Highway and asked me to add a few bonus tracks.

RM: Were those solo acoustic spots the precursor or catalyst for Del Bromham’s Blues Devils?

DB: Eventually. I started doing a few shows with a band backing me, one of the first of which was the Great British Rhythm and Blues Festival in Colne.

One of the guys from that event said "I’m so glad you’re doing the festival for us – by the way, what’s your band called?" I told him the band weren’t called anything, we were just using my name, but he said "you really have to let people know what it is you do!" – the old problem of having to put a label on the tin [laughs].

I told him I had an album called Devil’s Highway out, and that it was a blues album, so he immediately said "right, we’ll call it Del Bromham’s Blues Devils!" And me being me, I just said, "well right, OK then!" [laughs]

It was yet another accident, but one that stuck!

RM: Devil’s Highway is a great little album. It is, as you said, your take on the blues but there are some great throwback, Delta Blues styled songs in there and even a little soul blues and some country-pop blues.

DB: Those influences come from me being a big fan of the Spencer Davis Group when I was a teenager.

Autumn ’66 is still one of my favourite ever albums and that’s why Midnight Special is on the re-release of Devil's Highway. In fact I could have probably re-recorded the entire Autumn ’66 album I’m such a fan but I thought no, I’d better pace myself! [laughs].

Leslie had his Blues To Die For album out and Paul Newcomb managed to persuade him to come over to the UK to do a tour to promote it. Leslie said "OK, that’s great!" but then started to mention all these people he was going to bring over with him! [laughs].

Paul had to say "no, just come over with your acoustic guitar, tell some stories and play the songs solo."

Leslie said he couldn’t do that until Paul replied "well, Del Bromham does it."

Leslie replied "Del does it? Well, I’ll do it if Del does it with me!" [laughs].

So that’s how that little tour, and album, came about.

The re-release of Devil’s Highway you mentioned came about when I was doing the next album, Nine Yards. On the strength of the popularity of that one Angel Air Records decided to re-release Devil’s Highway and asked me to add a few bonus tracks.

RM: Were those solo acoustic spots the precursor or catalyst for Del Bromham’s Blues Devils?

DB: Eventually. I started doing a few shows with a band backing me, one of the first of which was the Great British Rhythm and Blues Festival in Colne.

One of the guys from that event said "I’m so glad you’re doing the festival for us – by the way, what’s your band called?" I told him the band weren’t called anything, we were just using my name, but he said "you really have to let people know what it is you do!" – the old problem of having to put a label on the tin [laughs].

I told him I had an album called Devil’s Highway out, and that it was a blues album, so he immediately said "right, we’ll call it Del Bromham’s Blues Devils!" And me being me, I just said, "well right, OK then!" [laughs]

It was yet another accident, but one that stuck!

RM: Devil’s Highway is a great little album. It is, as you said, your take on the blues but there are some great throwback, Delta Blues styled songs in there and even a little soul blues and some country-pop blues.

DB: Those influences come from me being a big fan of the Spencer Davis Group when I was a teenager.

Autumn ’66 is still one of my favourite ever albums and that’s why Midnight Special is on the re-release of Devil's Highway. In fact I could have probably re-recorded the entire Autumn ’66 album I’m such a fan but I thought no, I’d better pace myself! [laughs].

RM: Both Devil’s Highway and Nine Yards are very strong offerings but as I said earlier I believe White Feather to be your most accomplished and complete album.

It is very personal, as we’ve also discussed, yet it’s highly accessible and musically diverse, incorporating rock, pop, soul, a little funk and blues rock and those little Stray moments.

DB: Thank you very much, but that diversity also highlights the dilemma I had with White Feather.

I’m very aware, through the Blues Devils gigs and the Stray shows, that people have expectations on my guitar playing – on the full band shows my guitar playing is definitely going to come out but as I said before, it’s primarily, for me, about the songs.

One or two labels did pop their heads up to say they might be interested in my next album but I was very aware, once I got in to the studio, that it was going to be very much about the songs and not the guitar solos. There are a lot of guitar parts and guitars solos on there of course, as there always will be on anything I do, but it really is about the songs.

A lot of the blues labels are always looking for the next Stevie Ray Vaughan or Joe Bonamassa, or even the new Hendrix, so I knew they might be more than a little disappointed because they weren’t going to get that from me! [laughs].

But, once again, as with the Stray anthologies, it was Esoteric Recordings who were the most enthusiastic about the new album. I sent Mark and Vicky Powell a copy of the album on a Friday and all that weekend they were emailing me saying "this is brilliant, but it’s also very commercial."

I spoke to them on the phone and said "yes, there are definitely commercial tracks on there" because I could imagine, as you mentioned earlier, BBC Radio 2 playing some of the songs and getting White Feather out to a wider audience.

RM: That’s exactly where this album should be aimed and marketed; commerciality can still equate to quality music, whether pop or rock; no shame in that. White Feather deserves to reach that wider audience.

It is very personal, as we’ve also discussed, yet it’s highly accessible and musically diverse, incorporating rock, pop, soul, a little funk and blues rock and those little Stray moments.

DB: Thank you very much, but that diversity also highlights the dilemma I had with White Feather.

I’m very aware, through the Blues Devils gigs and the Stray shows, that people have expectations on my guitar playing – on the full band shows my guitar playing is definitely going to come out but as I said before, it’s primarily, for me, about the songs.

One or two labels did pop their heads up to say they might be interested in my next album but I was very aware, once I got in to the studio, that it was going to be very much about the songs and not the guitar solos. There are a lot of guitar parts and guitars solos on there of course, as there always will be on anything I do, but it really is about the songs.

A lot of the blues labels are always looking for the next Stevie Ray Vaughan or Joe Bonamassa, or even the new Hendrix, so I knew they might be more than a little disappointed because they weren’t going to get that from me! [laughs].

But, once again, as with the Stray anthologies, it was Esoteric Recordings who were the most enthusiastic about the new album. I sent Mark and Vicky Powell a copy of the album on a Friday and all that weekend they were emailing me saying "this is brilliant, but it’s also very commercial."

I spoke to them on the phone and said "yes, there are definitely commercial tracks on there" because I could imagine, as you mentioned earlier, BBC Radio 2 playing some of the songs and getting White Feather out to a wider audience.

RM: That’s exactly where this album should be aimed and marketed; commerciality can still equate to quality music, whether pop or rock; no shame in that. White Feather deserves to reach that wider audience.

DB: The funny thing is I didn’t go out of my way to do it that way but during production it was clear the songs were very much verses, choruses and hooks, with the hooks coming in pretty quick on some of the songs. The other thing I did, production wise, was to make sure there were little things mixed in there that you might not hear first time around but may pick up on six months later, much like the Beatles used to do on their later albums.

I just went back to my roots and remembered when I used to buy a record, sit the album cover on my lap and play it right through, one song after the other, and hear the differences between each song.

I made the comment to Jamie, about the fact the songs were all quite different, but that many of the labels want something that falls in to a genre – it has to be all blues, or it has to be all heavy rock, or it has to be something else! [laughs].

Jamie turned to me in the studio and said "this album Del, with the different styles of music and your lyrics, it’s almost like picking up a Del Bromham photograph album where you look at one photo from a particular time and place and then the next one is from a very different time and place."

I thought that was a brilliant way of explaining what I was trying to do – White Feather is very much like a photo album of different places in time.

RM: Snapshots of your life, in musical form.

DB: Yes, exactly, and it really works on that level, I believe.

I’m very proud of this album; it really is the album I’ve been waiting years to make. It has all the Del Bromham ingredients plus some stuff you’ve probably never heard me do before.

And to have a label that has been so enthusiastic about it is great. I’ve even had people approach me already about next year and when I’ll be performing, what sets I’ll be doing and what songs I’ll be playing, so it’s all onward, upward and forward as far as I’m concerned!

RM: Yes, you seem be even busier now than ever – certainly since the back in the Stray day, what with still performing as Stray plus the blues shows, whether they be solo or with the Blues Devils, and now White Feather.

DB: I was speaking to journalist Dave Ling at a gig not long ago and he said "Del, you don’t seem to be slowing down at all; haven’t you ever thought of retiring?"

I said "Dave, as far as I’m concerned I’ll be the B.B. King of Buckinghamshire!" [laughter].

B.B. went on to play right up until his late eighties and I have no intention of stopping.

I still feel like I’m eighteen – at least in my head [laughs] – and I still have the same desire I had all those long years ago.

RM: And as regards all those long years ago you are in the wonderful position of being able to revisit and relive them when you get together with Steve Gadd, Gary Giles and Ritchie Cole, the original line-up of Stray, for the occasional reunion show.

You’re one of the few bands with that sort of longevity and age who can still get together to perform and have such a great time doing it, That’s a win-win all round.

DB: The other thing that’s very pleasing about doing those shows was that a few people in the business implied that Stray might be past their sell-by date and might find it hard to sell tickets.

We did a couple of those reunion shows at The Borderline in London but they’ve had a few big names in there that never really pulled an audience.

But we were really doing it for the fun of it, much as you just said, and The Borderline was the one place we could play where we could get the guys together in the same place at the same time.

The first reunion show, we hadn’t played together for more than twenty years and we hadn’t even had a rehearsal – well, tell a lie, the rehearsal was the soundcheck in the afternoon! [laughter] – but what gave me the biggest thrill was that show sold out two months in advance.

When we did the second one it sold out again, and we were told unofficially that there were so many people trying to get in they had to let in more than they should have otherwise they might have had some trouble on their hands. So, unofficially, we may have broken the house record in there! [laughs].

We also did the British Rock and Blues Festival in Skegness – our venue for that show was absolutely jam packed – followed by The Giants of Rock at Minehead, where we played with our mates Uriah Heep.

They were queuing up to an hour before the gig to get in for that one. So much for being past our sell-by date!

RM: Fantastic. I can’t think of a better way to wrap up than talking about Stray still packing them in nearly fifty years on from the band’s earliest days – other than to ask you to pick a Stray song to play us out on…

DB: When I look back on my career with Stray and my particularly fond memories of our early days, the one song that reminds me of that time, and what we were trying to do, is Time Machine, off the first album.

I don’t honestly know what it is about that song but there is something about the atmosphere of that song.

People have asked me about perhaps re-recording it but sometimes you just can’t recapture that time, or that atmosphere.

Time Machine was also a little experimental and that ties in with what we were trying to say; we wanted to be slightly different from everyone else but at the same time it also has that catchy little melody in there, which goes back to what we’ve been saying about good songs and how it’s always about the song, first and foremost.

RM: It’s also the fitting soundtrack to a conversation that has jumped time to look back, reminisce, cover your entire career, brought us to the present with Stray in the twenty-first century and your future with White Feather and beyond.

Del, thank you so much for chatting so extensively with FabricationsHQ.

DB: Anytime, Ross, it’s been great talking to you again. Thank you very much for having me!

I just went back to my roots and remembered when I used to buy a record, sit the album cover on my lap and play it right through, one song after the other, and hear the differences between each song.

I made the comment to Jamie, about the fact the songs were all quite different, but that many of the labels want something that falls in to a genre – it has to be all blues, or it has to be all heavy rock, or it has to be something else! [laughs].

Jamie turned to me in the studio and said "this album Del, with the different styles of music and your lyrics, it’s almost like picking up a Del Bromham photograph album where you look at one photo from a particular time and place and then the next one is from a very different time and place."

I thought that was a brilliant way of explaining what I was trying to do – White Feather is very much like a photo album of different places in time.

RM: Snapshots of your life, in musical form.

DB: Yes, exactly, and it really works on that level, I believe.

I’m very proud of this album; it really is the album I’ve been waiting years to make. It has all the Del Bromham ingredients plus some stuff you’ve probably never heard me do before.

And to have a label that has been so enthusiastic about it is great. I’ve even had people approach me already about next year and when I’ll be performing, what sets I’ll be doing and what songs I’ll be playing, so it’s all onward, upward and forward as far as I’m concerned!

RM: Yes, you seem be even busier now than ever – certainly since the back in the Stray day, what with still performing as Stray plus the blues shows, whether they be solo or with the Blues Devils, and now White Feather.

DB: I was speaking to journalist Dave Ling at a gig not long ago and he said "Del, you don’t seem to be slowing down at all; haven’t you ever thought of retiring?"

I said "Dave, as far as I’m concerned I’ll be the B.B. King of Buckinghamshire!" [laughter].

B.B. went on to play right up until his late eighties and I have no intention of stopping.

I still feel like I’m eighteen – at least in my head [laughs] – and I still have the same desire I had all those long years ago.

RM: And as regards all those long years ago you are in the wonderful position of being able to revisit and relive them when you get together with Steve Gadd, Gary Giles and Ritchie Cole, the original line-up of Stray, for the occasional reunion show.

You’re one of the few bands with that sort of longevity and age who can still get together to perform and have such a great time doing it, That’s a win-win all round.

DB: The other thing that’s very pleasing about doing those shows was that a few people in the business implied that Stray might be past their sell-by date and might find it hard to sell tickets.

We did a couple of those reunion shows at The Borderline in London but they’ve had a few big names in there that never really pulled an audience.

But we were really doing it for the fun of it, much as you just said, and The Borderline was the one place we could play where we could get the guys together in the same place at the same time.

The first reunion show, we hadn’t played together for more than twenty years and we hadn’t even had a rehearsal – well, tell a lie, the rehearsal was the soundcheck in the afternoon! [laughter] – but what gave me the biggest thrill was that show sold out two months in advance.

When we did the second one it sold out again, and we were told unofficially that there were so many people trying to get in they had to let in more than they should have otherwise they might have had some trouble on their hands. So, unofficially, we may have broken the house record in there! [laughs].

We also did the British Rock and Blues Festival in Skegness – our venue for that show was absolutely jam packed – followed by The Giants of Rock at Minehead, where we played with our mates Uriah Heep.

They were queuing up to an hour before the gig to get in for that one. So much for being past our sell-by date!

RM: Fantastic. I can’t think of a better way to wrap up than talking about Stray still packing them in nearly fifty years on from the band’s earliest days – other than to ask you to pick a Stray song to play us out on…

DB: When I look back on my career with Stray and my particularly fond memories of our early days, the one song that reminds me of that time, and what we were trying to do, is Time Machine, off the first album.

I don’t honestly know what it is about that song but there is something about the atmosphere of that song.

People have asked me about perhaps re-recording it but sometimes you just can’t recapture that time, or that atmosphere.

Time Machine was also a little experimental and that ties in with what we were trying to say; we wanted to be slightly different from everyone else but at the same time it also has that catchy little melody in there, which goes back to what we’ve been saying about good songs and how it’s always about the song, first and foremost.

RM: It’s also the fitting soundtrack to a conversation that has jumped time to look back, reminisce, cover your entire career, brought us to the present with Stray in the twenty-first century and your future with White Feather and beyond.

Del, thank you so much for chatting so extensively with FabricationsHQ.

DB: Anytime, Ross, it’s been great talking to you again. Thank you very much for having me!

Muirsical Conversation with Del Bromham

Ross Muir

October 2018

Article dedicated to the memory of Zoe

"White feather's gonna fall"

All in Your mind 1970-1974, Fire & Glass 1975-1977 and White Feather are available from Esoteric Recordings

Photo Credit: Promo Image/ Lee Scriven

Ross Muir

October 2018

Article dedicated to the memory of Zoe

"White feather's gonna fall"

All in Your mind 1970-1974, Fire & Glass 1975-1977 and White Feather are available from Esoteric Recordings

Photo Credit: Promo Image/ Lee Scriven