The storied journey of a blues man

Muirsical Conversation with Gwyn Ashton

Gwyn Ashton is Australia’s greatest blues export and while European and American blues fans may think that’s a very small pool of muddy waters to fish from, there’s a far larger and more vibrant blues scene in the Land Down Under than many realise.

That fact was confirmed by Gwyn himself when the Welsh-born purveyor of gritty, high-energy blues rock talked to FabricationsHQ for what became an unscripted and extended Muirsical Conversation.

The following feature includes tales of tape recorders as amplifiers, harmonica players swinging upside down from rafters, travels from Adelaide to across America and a blues scene that so captivated a young Gwyn Ashton that his function/ hotel band became a blues band overnight.

Some of the vividly described stories had never been told by Gwyn before and the end result was a lengthy chat too good – and too entertaining – to edit down.

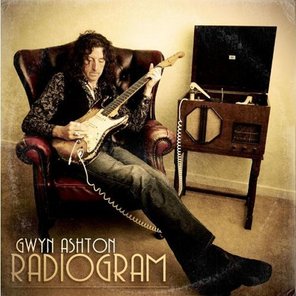

But the original premise of this particular feature was to talk about Radiogram (Gwyn’s sixth solo album and his best release to date) and his new band.

And that’s exactly where we started…

Ross Muir: There’s a real energy that comes off your latest album, Radiogram, which has that modern blues sound with a throwback feel in there as well. That was an intentional concept?

Gwyn Ashton: Yeah. Basically my favourite records are the classic albums from the 30’s to the 70’s.

We have modern technology these days to capture those sounds but I kind of prefer the older sounds of those classic records; they weren’t multi-tracked and layered or had everybody concentrating on getting the biggest drum sound or whatever… I just wanted the drums to sound like drums!

I’m not a fan of modern production. The tracks are always too well baffled with not a lot of microphone bleed. My favourite records, like Layla by Derek and the Dominos, that’s just a band setting up in basically one room and throwing a few microphones around the place, capturing a performance.

I wanted to create the atmosphere of a band playing together and I think I got that, because that’s what we did. If one of us made a mistake, we’d stop and start again. I don’t remember any drop-ins. I’m pretty sure we just played it until we got it right. Nothing was played more than two or three times, though; I hate to drag the vibe out of a song.

RM: Yes, sometimes you can over polish, or have too many layers, but there’s a real energy to album’s like Radiogram and kudos to you for doing something like that. It’s well worth the effort.

GA: Yeah, I think so. I mean there are overdubs because Kim Wilson wasn’t going to be hanging around, or Don Airey and Mark Stanway, or Robbie Blunt (laughs).

But I took my laptop to their houses and I just tracked them. I said "ok, here’s the track, just put your harmonica on this" or "put your keyboard on that…"

RM: And that gives the songs an extra dimension. But you still have that core sound of you and your guitars – and bass guitars – and Kevin Hickman on drums. But getting guys like Robbie and Don to contribute, that’s a feather in the cap in itself…

GA: Yeah. And with Don, he’s very busy with Deep Purple and doing other stuff. I emailed him the track, he put his part on it and we just mixed it back in. But they’re enhancements, that’s not the core band.

We go out and do the songs without those guys, obviously. But I think when you’re making a record you can get a few people in to enhance and embellish the sound to give it a broader spectrum.

It’s nice to be able to do that but it’s nice also to be able to go out as a trio, or even solo, and just play the songs and do something a little bit different with them.

RM: So you get that contrast between the live songs and the album versions.

GA: I’ve gone to see bands that sound just like the record and I think "well ok, you’ve practiced a lot guys, but where’s the soul?"

I wanna hear a mistake; I wanna hear somebody go “oh, shit, I shouldn’t have done that” (laughs).

RM: Which goes back to the earthiness and honesty of those earlier recordings and the energy of albums like Radiogram. I find that refreshing, because recordings like that are becoming the minority in this manufactured musical world we live in. Radiogram has captured more attention than any of your other albums – positive reviews in Europe, front cover feature on some magazines, blues album of the year nominations…

GA: Well there’s quite a cross-section of songs and I didn’t want a straightforward blues album – even though I play the blues! I wanted some songs on there that meant a varied amount of people could go and find at least one song they would like. I’d like to think that anyway.

If you like Americana or country you’re going to like Fortunate Kind. I’m playing some Weissenborn lap slide on that with Robbie Blunt playing lead guitar, so we have that dual guitar thing going on that a radio station in Nashville shouldn’t be ashamed to play. Comin’ Home has a bit of an old rock and roll, punk thing going on. It’s like Eddie Cochran meets Link Wray.

And I like to think that whatever style of music I’m playing, somebody who plays that style for a living could listen to it and go "he’s doing that correctly."

RM: Yeah, a musician’s musician. Or a musician’s album. Fortunate Kind is a great track.

GA: Robbie Blunt lives around the corner from me and I went round to his house with my laptop.

We were talking about all the classic albums we like, like Layla, and bands like The Allman Brothers.

And I played him this song and I said "why don’t we do something like that?" So that’s what we did!

That fact was confirmed by Gwyn himself when the Welsh-born purveyor of gritty, high-energy blues rock talked to FabricationsHQ for what became an unscripted and extended Muirsical Conversation.

The following feature includes tales of tape recorders as amplifiers, harmonica players swinging upside down from rafters, travels from Adelaide to across America and a blues scene that so captivated a young Gwyn Ashton that his function/ hotel band became a blues band overnight.

Some of the vividly described stories had never been told by Gwyn before and the end result was a lengthy chat too good – and too entertaining – to edit down.

But the original premise of this particular feature was to talk about Radiogram (Gwyn’s sixth solo album and his best release to date) and his new band.

And that’s exactly where we started…

Ross Muir: There’s a real energy that comes off your latest album, Radiogram, which has that modern blues sound with a throwback feel in there as well. That was an intentional concept?

Gwyn Ashton: Yeah. Basically my favourite records are the classic albums from the 30’s to the 70’s.

We have modern technology these days to capture those sounds but I kind of prefer the older sounds of those classic records; they weren’t multi-tracked and layered or had everybody concentrating on getting the biggest drum sound or whatever… I just wanted the drums to sound like drums!

I’m not a fan of modern production. The tracks are always too well baffled with not a lot of microphone bleed. My favourite records, like Layla by Derek and the Dominos, that’s just a band setting up in basically one room and throwing a few microphones around the place, capturing a performance.

I wanted to create the atmosphere of a band playing together and I think I got that, because that’s what we did. If one of us made a mistake, we’d stop and start again. I don’t remember any drop-ins. I’m pretty sure we just played it until we got it right. Nothing was played more than two or three times, though; I hate to drag the vibe out of a song.

RM: Yes, sometimes you can over polish, or have too many layers, but there’s a real energy to album’s like Radiogram and kudos to you for doing something like that. It’s well worth the effort.

GA: Yeah, I think so. I mean there are overdubs because Kim Wilson wasn’t going to be hanging around, or Don Airey and Mark Stanway, or Robbie Blunt (laughs).

But I took my laptop to their houses and I just tracked them. I said "ok, here’s the track, just put your harmonica on this" or "put your keyboard on that…"

RM: And that gives the songs an extra dimension. But you still have that core sound of you and your guitars – and bass guitars – and Kevin Hickman on drums. But getting guys like Robbie and Don to contribute, that’s a feather in the cap in itself…

GA: Yeah. And with Don, he’s very busy with Deep Purple and doing other stuff. I emailed him the track, he put his part on it and we just mixed it back in. But they’re enhancements, that’s not the core band.

We go out and do the songs without those guys, obviously. But I think when you’re making a record you can get a few people in to enhance and embellish the sound to give it a broader spectrum.

It’s nice to be able to do that but it’s nice also to be able to go out as a trio, or even solo, and just play the songs and do something a little bit different with them.

RM: So you get that contrast between the live songs and the album versions.

GA: I’ve gone to see bands that sound just like the record and I think "well ok, you’ve practiced a lot guys, but where’s the soul?"

I wanna hear a mistake; I wanna hear somebody go “oh, shit, I shouldn’t have done that” (laughs).

RM: Which goes back to the earthiness and honesty of those earlier recordings and the energy of albums like Radiogram. I find that refreshing, because recordings like that are becoming the minority in this manufactured musical world we live in. Radiogram has captured more attention than any of your other albums – positive reviews in Europe, front cover feature on some magazines, blues album of the year nominations…

GA: Well there’s quite a cross-section of songs and I didn’t want a straightforward blues album – even though I play the blues! I wanted some songs on there that meant a varied amount of people could go and find at least one song they would like. I’d like to think that anyway.

If you like Americana or country you’re going to like Fortunate Kind. I’m playing some Weissenborn lap slide on that with Robbie Blunt playing lead guitar, so we have that dual guitar thing going on that a radio station in Nashville shouldn’t be ashamed to play. Comin’ Home has a bit of an old rock and roll, punk thing going on. It’s like Eddie Cochran meets Link Wray.

And I like to think that whatever style of music I’m playing, somebody who plays that style for a living could listen to it and go "he’s doing that correctly."

RM: Yeah, a musician’s musician. Or a musician’s album. Fortunate Kind is a great track.

GA: Robbie Blunt lives around the corner from me and I went round to his house with my laptop.

We were talking about all the classic albums we like, like Layla, and bands like The Allman Brothers.

And I played him this song and I said "why don’t we do something like that?" So that’s what we did!

RM: I love the sound of the radiogram swing-arm tracking across at the top of the album, right before ‘Little Girl.’ Was it always the intention to use that effect?

GA: That was sort of an afterthought. But then I thought "that’s a good idea, let’s try that."

And you like it! (laughs).

RM: Well it’s a great effect and it’s a great intro. You always like to perform a cover or two on your albums and on Radiogram we have a great choice of cover – I Just Wanna Make Love by Willie Dixon.

Again, there’s that energy – and that Gwyn Ashton stamp – that fits the profile of Radiogram really well.

GA: Yeah, I think it fits in. I wanted to get a bit of… a modern-retro groove; I don’t know what you would call it (laughs). It’s a bit funky and a bit Hendrixy, I guess.

But I never try to rewrite music. A couple of criticisms have been that there’s no new territory being covered on the album but, you know, I wasn’t trying to do anything new (laughs), I was trying to play the kind of music that I like. And I wasn’t trying to go "you’ve never heard this before!" This is just my take on it.

I have fun playing guitar and at the end of the day you’ve got to enjoy what you do – there are no secret messages, it’s only rock ‘n roll…

RM: And no ulterior motive. There’s nothing here but the love of playing the music and the music itself.

And that’s just a musical truth; there’s nothing new in the blues, just how you interpret it, how you emote.

And that’s the key to the great blues guitar players and the great blues singers.

GA: Yeah. Anybody doing a blues album isn’t really doing anything new, unless you’re crossing genres like hip-hop and blues, guys like G. Love & Special Sauce.

I think they’re fantastic but a lot of the blues purists aren’t going to like it.

And Radiogram isn’t an album for any sort of purist, although if you are a purist hopefully you’ll find a song on there where I’ve captured the spirit of how it’s supposed to sound. But if you listen to the whole thing, expecting it to be just one thing, you’re going to be disappointed!

RM: It’s just a great modern blues album but with a throwback or retro feel to it.

We mentioned the Willie Dixon cover but the album closes out with Bluz for Roy, an instrumental that clearly has a nod, or is in tribute to, another great blues player, the late Roy Buchanan.

GA: Roy Buchanan is one of the greatest guitarists who ever lived and I wanted to pay homage, but I’m fully aware the song is probably too long! I toyed with the idea of editing it but then I thought if Roy did a track like that back in ’76, it would probably have gone on for about ten minutes! (laughs).

And for that track I just said to Kev "have a listen to this and then just join in."

And we just did it once, that was the one and only time we ever played it.

Kev said at the end of it "I messed up the end, let’s do it again" but I said "no, leave it like that."

And then he said "but do you think we should shorten it, or cut it up?" and I said "No. It’s honest, that’s how we played it." And it’s only a three-track song – there’s guitar, bass and one mike on the drums.

We could have done that on a four-track recorder and still had a track to spare!

RM: And you would have been dishonest to yourselves if you had edited that track or pro-tooled it because, again, that would be taking away from what Radiogram is saying and is exemplifying – honesty and energy.

GA: That song has got its own special dynamic because it does go up and down in level and, also, there are definite parts in it. So even thinking about trying to chop it up wouldn’t make any sense.

So I knew I would probably be the subject of criticism for such a long instrumental track, but I don’t care – it is what it is and it’s a tribute to Roy Buchanan. And he’s my hero, or one of them and if somebody doesn’t like it they can always hit the fast forward button (laughter).

Like in the good ol’ days, before individual tracks could be downloaded, I paid specific attention to the sequencing and each track was placed in listening order.

I even spent a couple of days working out how long the gaps were supposed to be between the tracks, so each one would have maximum impact when it came in to the next one. The modern approach these days is iTunes, just buying one track at a time, but a whole generation is missing out on how an album is a piece of art. Like Sgt. Pepper – you couldn’t put those songs in a different order because each one is telling a story. And Abbey Road; the same thing.

There’s a dying art in the way tracks relate to each other in a particular order.

RM: Yes, there’s a musical tapestry in those albums, weaving the whole thing together…

GA: And I know people are going to go to iTunes and just buy this track but not going to like that track, but they’re not going to give it a chance.

People make their minds up in five seconds if they like something. I used to buy a record and maybe I didn’t like the third song on that record but it was on the record. And it might take me ten, twelve, fifteen or even a hundred listens but finally the track I didn’t like in the first place I’m beginning to really like – I just didn’t get it the first time I heard it.

RM: The number of favourite songs I now have that are tracks from old vinyl records that I missed or, as you say, didn’t get the first time around, is extraordinary…

GA: And B-sides of singles! In the old days they used to put the inferior track on the B-side, or a track that wasn’t as important as the main song that you’re selling.

But quite often those B-sides were killer songs and if they weren’t there people wouldn’t have heard them! And it’s quite sad actually the way technology is making people lazy and they’re missing out.

RM: I was talking to Greg Lake recently about exactly the same things.

Obviously he’s another from the vinyl generation and he was talking about how records brought people together. You would share your musical experiences and listen to an entire record together.

I believe we’ve lost that in this MP3 player, iTunes and digital download age.

There’s a sterility attached to the musical experience now, the quick-fix of single tracks, manufactured music and the fashionable face-fits MTV brigade artists. Would you agree with that?

GA: Definitely. The Beatles song Ticket to Ride was the single off Help and Yes It Is was the B-side which never made it on to an album, but it’s one of their most beautiful songs; if it wasn’t on the B-side nobody would have heard it. But you flip that single over and you think "oh, what a great song!"

It’s a terrific song and it’s a shame it never made it on to an album, but maybe they didn’t think it was good enough. It might have been included on an American Beatles album?

RM: Yes, their earliest albums in America carried very different track listings and titles from the UK versions, or were more compilation…

GA: They had five albums made out of the first four, didn’t they?

RM: In the US yes, that’s right. Same sort of thing with the Rolling Stones, their first three or four albums had quite different track listings and album titles.

From vinyl record reminiscing back to your modern Radiogram – we mentioned Kev Hickman earlier, the drummer on Radiogram, but you have a new line-up featuring Mickey Barker on drums and Nick Skelson on bass…

GA: Yeah. Kev decided a few days after the album was released that he didn’t want to commit to it any more, so I really needed to focus in on getting a band to go out and promote this record.

And I thought "ok, I’ve had a duo for about ten years now but I haven’t had a trio for a while."

For the last few years I’ve just changed drummers but this time I thought I’d make it a bigger band because I wanted a more melodic role as a guitarist.

I loved doing the duo – I can get really rootsy and bluesy or just stay on root chord and hit the bottom end with my thumb and get real swampy and do the Mississippi sort of thing – but this time I wanted to add a bit more melody to the band and go out and play the songs off Radiogram with a bigger band.

And we’re going to enhance it further with Mark Stanway and Robbie Blunt, who are going to do a few shows with us next year, maybe the odd festival or two if we get any offers.

And having a bass player allows me to play a little bit differently – and just be a little bit more creative, I guess.

RM: You touched on the duo format, which gave you a great, earthy sound – that big drums and guitar sound…

GA: I’m not going to give that up entirely. There’s still going to be a time and a place for that – and I really enjoy doing it. Plus, with Mickey, we’re going to change the duo a little bit as well – a bit more acoustic and world, with the blues roots in there. I mean I’d like to play the Moroccan World music festival!

I’ve been listening to a lot of David Lindley, Ry Cooder, Ben Harper, plus different world grooves and I think we’re going to do something like that in the future.

There’s just so much music that I want to play and it’s going to come out soon.

And I'll start recording some acoustic stuff as well.

RM: That’s great to hear and that’s the true musician speaking – acknowledging there’s so much music still to explore even within the blues itself, which has roots in so many other genres…

GA: Oh absolutely. And Nick is a great addition to the band because he’s got a really solid low-end thing going. He’s not a high-tech slapping bass player or anything, he’s just got this fat bottom-end that growls and that’s really cool to get that ZZ Top - Rose Tattoo - AC/DC thing going on.

And I love all that too, so there’s definitely going to be a lot of rock and roll injected into this trio!

RM: And so far so good?

GA: Oh, yeah. We got the first gig out the way and it was surprisingly tight with a lot of vibe.

RM: Well in a way that doesn’t surprise me because we mentioned Mickey Barker coming in and I have heard, via the video you put up, some of the very first duo set you did with Mickey in Swindon. And you were saying that was virtually unrehearsed? You just started to jam?

GA: Completely unrehearsed, not virtually unrehearsed!

RM: Really?

GA: Yeah, totally unrehearsed. What happened was Kev and I had this gig but Kev couldn’t do it; he had something else to do.

And I sort of freaked out because the album was coming out and we had a pile of journalists coming up to review the show. So I asked Mickey, because about six years ago, before Kev was even playing this sort of music, I went to see Mickey playing with a band called Memphis in the Meantime, here in Worcestershire.

They were doing John Hiatt songs and all sorts of groovy stuff and I watched Mickey play and thought "I need this guy in my band!" What he was doing with a kick, snare and hi-hat most guys would struggle to do with a six-piece kit (laughs). And I said to myself "this is the most musical drummer I have ever seen."

I spoke to him but he was busy; he had other stuff to do and had commitments with his band. But when Kev couldn’t do this gig I rang Mickey up and said "do you wanna do a gig?"

So he came down to my house, we threw some stuff in the van and we were driving to Swindon when he said "I’m a little bit nervous about this because I haven’t got a clue what we’re going to play!"

And because I normally do a solo show I said "well, all you’ve got to do is just play drums and play whatever you think fits the song." The stuff I loaded up on Youtube is the very first song we ever played together.

RM: That’s incredible (laughs)…

GA: I said "Just think Bo Diddley for this one and let’s just go for it." In fact I don’t think I even said that!

I probably just said, about half-way through playing the intro, "Bo Diddley!" (laughter). And about four bars in to the song, when Mickey came in, I forgot – until the end of the night – that we’d never played together! (laughs).

RM: That’s a great summation of what you have together because clearly there’s chemistry there.

You seem to have an almost musical simpatico…

GA: I’ve never had that with anybody before – ever! It’s usually a case of "ok, we’re gonna be doing this so here’s ten albums. Go and listen to this stuff and then you can come and play with me." But this time it was "Just play – play whatever you feel" because Mickey is such a good percussionist and drummer.

I’d never really heard Magnum until last year when I went on the road and played with them but Mickey wasn’t in the band then – he left in ‘95 I think.

I’m actually taking him out to see Magnum tomorrow night – he hasn’t seen all the guys since ’95, so it’ll be a bit of a fun night!

GA: That was sort of an afterthought. But then I thought "that’s a good idea, let’s try that."

And you like it! (laughs).

RM: Well it’s a great effect and it’s a great intro. You always like to perform a cover or two on your albums and on Radiogram we have a great choice of cover – I Just Wanna Make Love by Willie Dixon.

Again, there’s that energy – and that Gwyn Ashton stamp – that fits the profile of Radiogram really well.

GA: Yeah, I think it fits in. I wanted to get a bit of… a modern-retro groove; I don’t know what you would call it (laughs). It’s a bit funky and a bit Hendrixy, I guess.

But I never try to rewrite music. A couple of criticisms have been that there’s no new territory being covered on the album but, you know, I wasn’t trying to do anything new (laughs), I was trying to play the kind of music that I like. And I wasn’t trying to go "you’ve never heard this before!" This is just my take on it.

I have fun playing guitar and at the end of the day you’ve got to enjoy what you do – there are no secret messages, it’s only rock ‘n roll…

RM: And no ulterior motive. There’s nothing here but the love of playing the music and the music itself.

And that’s just a musical truth; there’s nothing new in the blues, just how you interpret it, how you emote.

And that’s the key to the great blues guitar players and the great blues singers.

GA: Yeah. Anybody doing a blues album isn’t really doing anything new, unless you’re crossing genres like hip-hop and blues, guys like G. Love & Special Sauce.

I think they’re fantastic but a lot of the blues purists aren’t going to like it.

And Radiogram isn’t an album for any sort of purist, although if you are a purist hopefully you’ll find a song on there where I’ve captured the spirit of how it’s supposed to sound. But if you listen to the whole thing, expecting it to be just one thing, you’re going to be disappointed!

RM: It’s just a great modern blues album but with a throwback or retro feel to it.

We mentioned the Willie Dixon cover but the album closes out with Bluz for Roy, an instrumental that clearly has a nod, or is in tribute to, another great blues player, the late Roy Buchanan.

GA: Roy Buchanan is one of the greatest guitarists who ever lived and I wanted to pay homage, but I’m fully aware the song is probably too long! I toyed with the idea of editing it but then I thought if Roy did a track like that back in ’76, it would probably have gone on for about ten minutes! (laughs).

And for that track I just said to Kev "have a listen to this and then just join in."

And we just did it once, that was the one and only time we ever played it.

Kev said at the end of it "I messed up the end, let’s do it again" but I said "no, leave it like that."

And then he said "but do you think we should shorten it, or cut it up?" and I said "No. It’s honest, that’s how we played it." And it’s only a three-track song – there’s guitar, bass and one mike on the drums.

We could have done that on a four-track recorder and still had a track to spare!

RM: And you would have been dishonest to yourselves if you had edited that track or pro-tooled it because, again, that would be taking away from what Radiogram is saying and is exemplifying – honesty and energy.

GA: That song has got its own special dynamic because it does go up and down in level and, also, there are definite parts in it. So even thinking about trying to chop it up wouldn’t make any sense.

So I knew I would probably be the subject of criticism for such a long instrumental track, but I don’t care – it is what it is and it’s a tribute to Roy Buchanan. And he’s my hero, or one of them and if somebody doesn’t like it they can always hit the fast forward button (laughter).

Like in the good ol’ days, before individual tracks could be downloaded, I paid specific attention to the sequencing and each track was placed in listening order.

I even spent a couple of days working out how long the gaps were supposed to be between the tracks, so each one would have maximum impact when it came in to the next one. The modern approach these days is iTunes, just buying one track at a time, but a whole generation is missing out on how an album is a piece of art. Like Sgt. Pepper – you couldn’t put those songs in a different order because each one is telling a story. And Abbey Road; the same thing.

There’s a dying art in the way tracks relate to each other in a particular order.

RM: Yes, there’s a musical tapestry in those albums, weaving the whole thing together…

GA: And I know people are going to go to iTunes and just buy this track but not going to like that track, but they’re not going to give it a chance.

People make their minds up in five seconds if they like something. I used to buy a record and maybe I didn’t like the third song on that record but it was on the record. And it might take me ten, twelve, fifteen or even a hundred listens but finally the track I didn’t like in the first place I’m beginning to really like – I just didn’t get it the first time I heard it.

RM: The number of favourite songs I now have that are tracks from old vinyl records that I missed or, as you say, didn’t get the first time around, is extraordinary…

GA: And B-sides of singles! In the old days they used to put the inferior track on the B-side, or a track that wasn’t as important as the main song that you’re selling.

But quite often those B-sides were killer songs and if they weren’t there people wouldn’t have heard them! And it’s quite sad actually the way technology is making people lazy and they’re missing out.

RM: I was talking to Greg Lake recently about exactly the same things.

Obviously he’s another from the vinyl generation and he was talking about how records brought people together. You would share your musical experiences and listen to an entire record together.

I believe we’ve lost that in this MP3 player, iTunes and digital download age.

There’s a sterility attached to the musical experience now, the quick-fix of single tracks, manufactured music and the fashionable face-fits MTV brigade artists. Would you agree with that?

GA: Definitely. The Beatles song Ticket to Ride was the single off Help and Yes It Is was the B-side which never made it on to an album, but it’s one of their most beautiful songs; if it wasn’t on the B-side nobody would have heard it. But you flip that single over and you think "oh, what a great song!"

It’s a terrific song and it’s a shame it never made it on to an album, but maybe they didn’t think it was good enough. It might have been included on an American Beatles album?

RM: Yes, their earliest albums in America carried very different track listings and titles from the UK versions, or were more compilation…

GA: They had five albums made out of the first four, didn’t they?

RM: In the US yes, that’s right. Same sort of thing with the Rolling Stones, their first three or four albums had quite different track listings and album titles.

From vinyl record reminiscing back to your modern Radiogram – we mentioned Kev Hickman earlier, the drummer on Radiogram, but you have a new line-up featuring Mickey Barker on drums and Nick Skelson on bass…

GA: Yeah. Kev decided a few days after the album was released that he didn’t want to commit to it any more, so I really needed to focus in on getting a band to go out and promote this record.

And I thought "ok, I’ve had a duo for about ten years now but I haven’t had a trio for a while."

For the last few years I’ve just changed drummers but this time I thought I’d make it a bigger band because I wanted a more melodic role as a guitarist.

I loved doing the duo – I can get really rootsy and bluesy or just stay on root chord and hit the bottom end with my thumb and get real swampy and do the Mississippi sort of thing – but this time I wanted to add a bit more melody to the band and go out and play the songs off Radiogram with a bigger band.

And we’re going to enhance it further with Mark Stanway and Robbie Blunt, who are going to do a few shows with us next year, maybe the odd festival or two if we get any offers.

And having a bass player allows me to play a little bit differently – and just be a little bit more creative, I guess.

RM: You touched on the duo format, which gave you a great, earthy sound – that big drums and guitar sound…

GA: I’m not going to give that up entirely. There’s still going to be a time and a place for that – and I really enjoy doing it. Plus, with Mickey, we’re going to change the duo a little bit as well – a bit more acoustic and world, with the blues roots in there. I mean I’d like to play the Moroccan World music festival!

I’ve been listening to a lot of David Lindley, Ry Cooder, Ben Harper, plus different world grooves and I think we’re going to do something like that in the future.

There’s just so much music that I want to play and it’s going to come out soon.

And I'll start recording some acoustic stuff as well.

RM: That’s great to hear and that’s the true musician speaking – acknowledging there’s so much music still to explore even within the blues itself, which has roots in so many other genres…

GA: Oh absolutely. And Nick is a great addition to the band because he’s got a really solid low-end thing going. He’s not a high-tech slapping bass player or anything, he’s just got this fat bottom-end that growls and that’s really cool to get that ZZ Top - Rose Tattoo - AC/DC thing going on.

And I love all that too, so there’s definitely going to be a lot of rock and roll injected into this trio!

RM: And so far so good?

GA: Oh, yeah. We got the first gig out the way and it was surprisingly tight with a lot of vibe.

RM: Well in a way that doesn’t surprise me because we mentioned Mickey Barker coming in and I have heard, via the video you put up, some of the very first duo set you did with Mickey in Swindon. And you were saying that was virtually unrehearsed? You just started to jam?

GA: Completely unrehearsed, not virtually unrehearsed!

RM: Really?

GA: Yeah, totally unrehearsed. What happened was Kev and I had this gig but Kev couldn’t do it; he had something else to do.

And I sort of freaked out because the album was coming out and we had a pile of journalists coming up to review the show. So I asked Mickey, because about six years ago, before Kev was even playing this sort of music, I went to see Mickey playing with a band called Memphis in the Meantime, here in Worcestershire.

They were doing John Hiatt songs and all sorts of groovy stuff and I watched Mickey play and thought "I need this guy in my band!" What he was doing with a kick, snare and hi-hat most guys would struggle to do with a six-piece kit (laughs). And I said to myself "this is the most musical drummer I have ever seen."

I spoke to him but he was busy; he had other stuff to do and had commitments with his band. But when Kev couldn’t do this gig I rang Mickey up and said "do you wanna do a gig?"

So he came down to my house, we threw some stuff in the van and we were driving to Swindon when he said "I’m a little bit nervous about this because I haven’t got a clue what we’re going to play!"

And because I normally do a solo show I said "well, all you’ve got to do is just play drums and play whatever you think fits the song." The stuff I loaded up on Youtube is the very first song we ever played together.

RM: That’s incredible (laughs)…

GA: I said "Just think Bo Diddley for this one and let’s just go for it." In fact I don’t think I even said that!

I probably just said, about half-way through playing the intro, "Bo Diddley!" (laughter). And about four bars in to the song, when Mickey came in, I forgot – until the end of the night – that we’d never played together! (laughs).

RM: That’s a great summation of what you have together because clearly there’s chemistry there.

You seem to have an almost musical simpatico…

GA: I’ve never had that with anybody before – ever! It’s usually a case of "ok, we’re gonna be doing this so here’s ten albums. Go and listen to this stuff and then you can come and play with me." But this time it was "Just play – play whatever you feel" because Mickey is such a good percussionist and drummer.

I’d never really heard Magnum until last year when I went on the road and played with them but Mickey wasn’t in the band then – he left in ‘95 I think.

I’m actually taking him out to see Magnum tomorrow night – he hasn’t seen all the guys since ’95, so it’ll be a bit of a fun night!

Nick Skelson, Mickey Barker and Gwyn Ashton

"There’s definitely going to be a lot of rock and roll injected into this trio!"

GA: And Mickey is such a good player that I had no doubt he would fit straight in.

So when I needed a drummer, after Kev left, I just rung him up and said "do you want to join my band?" And he said "that was a great night, wasn’t it? Let’s do it!"

So I put the new band together in the car park at Sainsburys, over the telephone! (laughs).

RM: With Mickey and Nick It certainly bodes well for the future but if I can take you back to your past, Gwyn, and ask: how does a Welsh born Aussie get into the blues – and the guitar – in the first place?

GA: Well, the first time I saw a guitar I was about three years old – I was watching Freddie and The Dreamers on television but I probably didn’t really see the guitarist because of all the silly dance moves! But I just thought it was cool and then I heard The Beatles on the radio. And when I was about nine years old I went to stay with my brother and he played a bit of acoustic guitar.

He had a guitar in the living room and I was mesmerised by it, I wanted to play it!

I thought about it for about four years but then, in 1972, my mother bought me a guitar. It was ten dollars from the junk shop on the corner and it was this horrible acoustic thing (laughs) – but I loved it!

And my brother got me the Children’s Guitar Guide by Happy Traum, a great American guitar player, and I just sat down and taught myself out of this book and it immediately became my best friend. And that led to me buying an electric guitar.

Actually, before I bought an electric guitar I thought I needed an electric guitar (laughs) so I got my reel-to-reel tape recorder and a little microphone and I stuck that in the sound hole of my guitar. I put the tape recorder on Record and Pause and I had this great electric guitar – well, I thought! (laughs)

RM: I did exactly the same thing! I don’t play guitar but at about that same age I learned that very same trick and had this wonderful sound. Or so you think, but it makes you feel like a rock God – until you blow out your tape recorder (laughs). Just great times…

GA: It blew me away! I couldn’t believe the sound and people are still doing that, putting tiny little microphones in guitars and putting that through a pre-amp or whatever… and I thought I invented that!

I really thought "I’m a genius (laughs), making an electric guitar amp out of my tape recorder!"

RM: Only to find out it was a universal trick used by every kid who wanted to be a rock guitar God – the equivalent of the wannabe singers posing in front of the mirror with a hair dryer for a microphone…

GA: Yeah, and ten years before 1973 every kid in England was doing exactly the same thing but in front of a mirror with a tennis racket (laughs), pretending to be Hank Marvin…

RM: That’s right. Hank Marvin, back then, would be the one everybody wanted to be – and practising The Shadows walk...

GA: Actually that tape recorder? The tape I had was a pre-recorded tape and it was The Shadows Greatest Hits! I listened to that on my reel-to-reel tape recorder every day and I used to think "wow, this is great!"

So I got into that and The Goon Show. Those were the two tapes I had!

RM: But that’s not a bad double-tape set to have (laughs). So by this time your family had emigrated to Australia?

GA: Yep, I lived in South Australia, actually in a place called Macclesfield in the Adelaide Hills – and I’m playing Macclesfield in England this coming Saturday (laughs)!

RM: Small worlds (laughs). So you have the guitar bug, but what gave you the blues bug and when did you get into the blues rock vibe?

GA: A few years later. I had got my electric guitar and I read in the paper that someone was looking for a guitarist and so I went and joined this band.

The band didn’t really work out but one of the guys in the band, singer/ guitarist Niel Edgley, became a life-long friend. We still talk even now but this was back in ‘75, ’76, when I saw the ad in the paper.

I still didn’t have an amplifier at the time because I didn’t really have any money, so we just plugged into whatever was around the place and Niel was a crazy guy that lived just near the beach and we had all these crazy old cars! He had a ’65 Ford falcon and I had a ’60 Chevy Bel-Air.

Great times, but we were playing this 50’s rock and roll and 60’s stuff – we were doing The Platters, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Creedence Clearwater Revival.

It was cabaret, basically, but it was fun and it was my first band and it was real rock and roll stuff. But I had no idea back then that it was all blues based.

In fact in 1972, when I first really started listening to the radio, my favourite songs were blues and country numbers but I had no idea they were the roots of what I was to later immerse myself in.

RM: Pointing to what your musical future would be…

GA: Yeah. And there were a lot of Australian artists at that time that no-one would have heard of over here. There was a band called Blackfeather and they had a big hit called Boppin’ the Blues. Didn’t know what the blues was but it was a great song! Totally different to the Carl Perkins number – different song altogether. And there was Gypsy Queen by Country Radio, which was a folky sort of song but blues related. And Dave Edmunds was around with Promised Land but I didn’t know that was a Chuck Berry song.

So they were all on the radio constantly…

RM: So the seeds were being sown…

GA: Yeah, and a year later Niel said "I’m going to take you guys out to see a blues band tomorrow night."

I turned around with the rest of the guys and said "Blues? That’s old people’s music, isn’t it?" (laughter).

I was seventeen years old and I had no idea because my parents didn’t listen to that sort of stuff – they came from an age where that was race music, the devil’s music. You didn’t listen to that in a white household. Which was a shame, but my parents weren’t into that sort of stuff at all.

So anyway I went along – the drummer in the band didn’t go because he had things to do with his girlfriend or whatever (laughter) – but I said “ok, I’ll go along.” That decision changed my life entirely.

The band was called Smokestack Lightning and they were a local Adelaide band playing in the Adelaide Hills at this pub called the Aldgate Pumphouse Hotel.

The Adelaide Hills region had a hippy community in those days, full of people that I had never encountered before because I had a conservative upbringing.

And suddenly I was in a room full of these people who are smoking funny tobacco and drinking lots of beer. But I got turned on to this incredibly loud Chicago blues band – from Adelaide! But they were really good and they were really tough.

They had big amplifiers and they had this attitude, with long hair and low-slung guitars. And I remember the drummer played the most incredible Chicago shuffle that I’ve ever heard – I didn’t even know what one was at the time but I learned later on – and that sort of music was their upbringing.

It just turned me on straight away and the next day I went out with Niel to the local record store on the beach. I come from a beach area of Australia where everybody had a surf board and panel vans and we used to go and catch waves – anyway, I bought John Mayall’s Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton and a Smokestack Lightning album, took them home and played the hell outta them.

And that’s how I first got into the blues.

RM: Well and truly bitten by the blues bug…

GA: Oh, yeah. And then it was "well, there must be more blues bands in Adelaide, let’s go and see them!" Then my band automatically became a blues band overnight!

RM: I was going to say that experience must have been an instant musical transformation (laughs)…

GA: It was! We were playing in the Barossa Valley, which is a tourist/ wine country place and every Friday night we would play the Sunset Boulevard Hotel.

That was a very nice cabaret venue with mums, dads and their kids all having dinner and we were the dance band; we were called Brass Monkey! (laughter).

We were playing all this nice stuff and did some waltzes but the next week I’d given all that up and we were a blues band – we were playing Muddy Waters!

So we get there, we start playing and half-way through the night the owner of the restaurant comes running – he was pulling his hair out – and says "what are you guys doing! You were so good last week, what is this you’re playing now? What’s this noise?" (laughter). We just said "We’re a blues band now, man" (laughs). "We’re not playing that other stuff any more – this is what we are."

I think we did it one more time… but that was about it, and I’ve been scaring people out of venues ever since!

RM: And so you began to learn your trade in the blues…

GA: Yeah. A few weeks later we got a different drummer, because my drummer had a girlfriend and that was a pain in the arse (laughter). So anyway we got another drummer and that was Chris Land, who is still a very good friend of mine in Adelaide.

And Chris said "I’m going to take you out tonight to see Chris Finnen and the band Mickey Finn."

And I went "Who are they?" Chris said "You’ll love ‘em!"

Chris Finnen was suddenly not only my mentor but also became one of my longest standing friends and I still regard him as the best, white electric blues guitar player on the planet. He’s also a really good percussionist and is adept on African and Indian hand drums. He opened my mind to a lot of other music.

But to see Chris in this psychedelic blues trio was eye-opening. It was like "Who is this guy?"

I’d never seen anybody play guitar like this guy before and he’s playing better than ever now!

It’s a shame nobody’s ever heard of him outside of Australia and it’s only since he ended up working with people outside of South Australia that the rest of the country has even heard of him.

RM: I assume he still concentrates on his home area with no real urge to go beyond?

GA: I don’t think it’s an urge issue. Australia’s a pretty big place and in those days we didn’t really think of a global situation.

So, anyway, Chris Finnen was opening for a local band called Mickey Finn, ex- Fraternity who Bon Scott fronted before he joined AC/DC. When Bon left Jimmy Barnes took his place...

RM: Oh, he’s not a bad singer and fairly well known (laughs).

GA: Jimmy’s brother Swanee, who I briefly played with in the 80’s, was the drummer in that band. He’s a great singer, too.

So this is the history of Mickey Finn, this fabulous, hard rockin’ R&B AC/DC type boogie ‘n’ blues band with a mad front man Uncle John Ayers who used to hang upside down from the rafters (laughter) and play really wicked blues harmonica! These were the days of big PA systems and Uncle would climb up on top of the PA and jump off and people would catch him – but he would be blowing his harmonica the entire time!

And if he fell over and hurt himself he wouldn’t have felt it anyway, because he was too anaesthetised (laughs) from whatever he had been taking that day!

RM: Great story. That whole scene and vibe you’ve just described – that wonderful, hard rock energy within a blues format – clearly that was an influence because you carry that through your own music and solo albums…

GA: Oh yeah, yeah, the whole Australian rock and roll thing. These guys had 2 x 100 watt Marshalls each (laughs), they weren’t there with a nice little Fender twin reverb. They meant business.

And their attitude was it’s not playing in a band, it’s war. It was a military procedure on stage – the stage was where you had to carry out this intricate operation. And that was their attitude towards playing.

That’s where I developed my sense of focus for a band. Now everybody wants to play with everybody else – everybody wants to be a bloody session player!

You know, this guy wants to play with that band and this band, then with that bloke over there; bass players want to be in ten bands… and that’s not a team spirit.

If you are in a band you’ve got to have the camaraderie and you’ve got to have the communication and the focus and the goal. That’s the old band spirit.

I was watching Chris Robinson on Youtube last night and he was talking, back in ‘95 or something like that, about exactly that. And I thought to myself that’s why guys like that succeed, because they have a community spirit within their band and nobody can touch that.

John Lennon didn’t go running off with the Rolling Stones to do a few gigs with them. When times were tough, they didn’t go and join other bands; they ate dog food and slept on pool tables, because they believed in what they did.

RM: That’s exactly what it comes down to – belief in the music and having that focus, that drive. It’s still around but it’s not for every band.

There are acts out there that can plug in a replacement, session musician or a tribute singer at the drop of a hi-hat and go out and play what are predominately Greatest Hits sets. And that’s fine, because that’s what sells and that’s what the majority seem to want.

But the camaraderie, the group chemistry, that’s something we don’t see so much of in this reimagined day and age, not when compared to the musical melting pot of the 70’s and that whole creative period.

GA: And in the 60’s, when Ringo got tonsillitis and Jimmy Nicol had to fill in on drums. But it wasn’t the same, you know?

RM: No, absolutely. Thanks for sharing those great stories about your formative years and the blues scene in Australia.

But by the early 90’s you’re telling your own blues stories – in 1993 you released your debut album Feel the Heat and three years later Beg, Borrow and Steel. There’s a lovely contrast between the two albums – the debut is modern blues rock while Beg, Borrow and Steel is acoustic based…

GA: Well what happened was – and I haven’t told anyone this story – I wanted to do an acoustic album, because I was leaving Australia and I needed something I could go out with and be play by myself and do solo gigs. But I didn’t have any money, so I traded a piece of studio gear for a day’s studio time.

They knew that I had it and they always wanted to buy it off me, so I said I was going to sell it.

It was worth five hundred dollars and the studio was five hundred dollars a day. So I said "do you mind if I do a day in your studio and I give you the Roland Dimension D?" and they said "no, that’s great."

But what they didn’t stipulate was how long a studio day went on for (laughter).

These days in a studio a day is eight or ten hours, but we didn’t exactly agree on how long a day was (laughs), so I went in at ten o’clock in the morning to record Beg, Borrow and Steel and I left the studio at ten o’clock the next morning!

A few days earlier I’d thought it would be nice to have a few friends play on this, so I just rang around and said "Look, I’m doing a session the day after tomorrow, do you want to come down the studio and play?"

And they all said ok, so it became a jam – the whole thing was a jam session.

The keyboard player, Mick O’Conner, had a gig up the road from the studio so he could come in just before sound check and he could come in after the gig, at one in the morning! (laughs).

So I went in at ten o’clock in the morning and put down most of the tracks I had to play on, by myself, then the other guys dribbled in during the day.

I was pretty tired (laughs), but the whole album was mixed at ten o’clock that next morning. I did an album in 24 hours, mixed it and came out with a two-track mix ready to master!

"There’s definitely going to be a lot of rock and roll injected into this trio!"

GA: And Mickey is such a good player that I had no doubt he would fit straight in.

So when I needed a drummer, after Kev left, I just rung him up and said "do you want to join my band?" And he said "that was a great night, wasn’t it? Let’s do it!"

So I put the new band together in the car park at Sainsburys, over the telephone! (laughs).

RM: With Mickey and Nick It certainly bodes well for the future but if I can take you back to your past, Gwyn, and ask: how does a Welsh born Aussie get into the blues – and the guitar – in the first place?

GA: Well, the first time I saw a guitar I was about three years old – I was watching Freddie and The Dreamers on television but I probably didn’t really see the guitarist because of all the silly dance moves! But I just thought it was cool and then I heard The Beatles on the radio. And when I was about nine years old I went to stay with my brother and he played a bit of acoustic guitar.

He had a guitar in the living room and I was mesmerised by it, I wanted to play it!

I thought about it for about four years but then, in 1972, my mother bought me a guitar. It was ten dollars from the junk shop on the corner and it was this horrible acoustic thing (laughs) – but I loved it!

And my brother got me the Children’s Guitar Guide by Happy Traum, a great American guitar player, and I just sat down and taught myself out of this book and it immediately became my best friend. And that led to me buying an electric guitar.

Actually, before I bought an electric guitar I thought I needed an electric guitar (laughs) so I got my reel-to-reel tape recorder and a little microphone and I stuck that in the sound hole of my guitar. I put the tape recorder on Record and Pause and I had this great electric guitar – well, I thought! (laughs)

RM: I did exactly the same thing! I don’t play guitar but at about that same age I learned that very same trick and had this wonderful sound. Or so you think, but it makes you feel like a rock God – until you blow out your tape recorder (laughs). Just great times…

GA: It blew me away! I couldn’t believe the sound and people are still doing that, putting tiny little microphones in guitars and putting that through a pre-amp or whatever… and I thought I invented that!

I really thought "I’m a genius (laughs), making an electric guitar amp out of my tape recorder!"

RM: Only to find out it was a universal trick used by every kid who wanted to be a rock guitar God – the equivalent of the wannabe singers posing in front of the mirror with a hair dryer for a microphone…

GA: Yeah, and ten years before 1973 every kid in England was doing exactly the same thing but in front of a mirror with a tennis racket (laughs), pretending to be Hank Marvin…

RM: That’s right. Hank Marvin, back then, would be the one everybody wanted to be – and practising The Shadows walk...

GA: Actually that tape recorder? The tape I had was a pre-recorded tape and it was The Shadows Greatest Hits! I listened to that on my reel-to-reel tape recorder every day and I used to think "wow, this is great!"

So I got into that and The Goon Show. Those were the two tapes I had!

RM: But that’s not a bad double-tape set to have (laughs). So by this time your family had emigrated to Australia?

GA: Yep, I lived in South Australia, actually in a place called Macclesfield in the Adelaide Hills – and I’m playing Macclesfield in England this coming Saturday (laughs)!

RM: Small worlds (laughs). So you have the guitar bug, but what gave you the blues bug and when did you get into the blues rock vibe?

GA: A few years later. I had got my electric guitar and I read in the paper that someone was looking for a guitarist and so I went and joined this band.

The band didn’t really work out but one of the guys in the band, singer/ guitarist Niel Edgley, became a life-long friend. We still talk even now but this was back in ‘75, ’76, when I saw the ad in the paper.

I still didn’t have an amplifier at the time because I didn’t really have any money, so we just plugged into whatever was around the place and Niel was a crazy guy that lived just near the beach and we had all these crazy old cars! He had a ’65 Ford falcon and I had a ’60 Chevy Bel-Air.

Great times, but we were playing this 50’s rock and roll and 60’s stuff – we were doing The Platters, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Creedence Clearwater Revival.

It was cabaret, basically, but it was fun and it was my first band and it was real rock and roll stuff. But I had no idea back then that it was all blues based.

In fact in 1972, when I first really started listening to the radio, my favourite songs were blues and country numbers but I had no idea they were the roots of what I was to later immerse myself in.

RM: Pointing to what your musical future would be…

GA: Yeah. And there were a lot of Australian artists at that time that no-one would have heard of over here. There was a band called Blackfeather and they had a big hit called Boppin’ the Blues. Didn’t know what the blues was but it was a great song! Totally different to the Carl Perkins number – different song altogether. And there was Gypsy Queen by Country Radio, which was a folky sort of song but blues related. And Dave Edmunds was around with Promised Land but I didn’t know that was a Chuck Berry song.

So they were all on the radio constantly…

RM: So the seeds were being sown…

GA: Yeah, and a year later Niel said "I’m going to take you guys out to see a blues band tomorrow night."

I turned around with the rest of the guys and said "Blues? That’s old people’s music, isn’t it?" (laughter).

I was seventeen years old and I had no idea because my parents didn’t listen to that sort of stuff – they came from an age where that was race music, the devil’s music. You didn’t listen to that in a white household. Which was a shame, but my parents weren’t into that sort of stuff at all.

So anyway I went along – the drummer in the band didn’t go because he had things to do with his girlfriend or whatever (laughter) – but I said “ok, I’ll go along.” That decision changed my life entirely.

The band was called Smokestack Lightning and they were a local Adelaide band playing in the Adelaide Hills at this pub called the Aldgate Pumphouse Hotel.

The Adelaide Hills region had a hippy community in those days, full of people that I had never encountered before because I had a conservative upbringing.

And suddenly I was in a room full of these people who are smoking funny tobacco and drinking lots of beer. But I got turned on to this incredibly loud Chicago blues band – from Adelaide! But they were really good and they were really tough.

They had big amplifiers and they had this attitude, with long hair and low-slung guitars. And I remember the drummer played the most incredible Chicago shuffle that I’ve ever heard – I didn’t even know what one was at the time but I learned later on – and that sort of music was their upbringing.

It just turned me on straight away and the next day I went out with Niel to the local record store on the beach. I come from a beach area of Australia where everybody had a surf board and panel vans and we used to go and catch waves – anyway, I bought John Mayall’s Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton and a Smokestack Lightning album, took them home and played the hell outta them.

And that’s how I first got into the blues.

RM: Well and truly bitten by the blues bug…

GA: Oh, yeah. And then it was "well, there must be more blues bands in Adelaide, let’s go and see them!" Then my band automatically became a blues band overnight!

RM: I was going to say that experience must have been an instant musical transformation (laughs)…

GA: It was! We were playing in the Barossa Valley, which is a tourist/ wine country place and every Friday night we would play the Sunset Boulevard Hotel.

That was a very nice cabaret venue with mums, dads and their kids all having dinner and we were the dance band; we were called Brass Monkey! (laughter).

We were playing all this nice stuff and did some waltzes but the next week I’d given all that up and we were a blues band – we were playing Muddy Waters!

So we get there, we start playing and half-way through the night the owner of the restaurant comes running – he was pulling his hair out – and says "what are you guys doing! You were so good last week, what is this you’re playing now? What’s this noise?" (laughter). We just said "We’re a blues band now, man" (laughs). "We’re not playing that other stuff any more – this is what we are."

I think we did it one more time… but that was about it, and I’ve been scaring people out of venues ever since!

RM: And so you began to learn your trade in the blues…

GA: Yeah. A few weeks later we got a different drummer, because my drummer had a girlfriend and that was a pain in the arse (laughter). So anyway we got another drummer and that was Chris Land, who is still a very good friend of mine in Adelaide.

And Chris said "I’m going to take you out tonight to see Chris Finnen and the band Mickey Finn."

And I went "Who are they?" Chris said "You’ll love ‘em!"

Chris Finnen was suddenly not only my mentor but also became one of my longest standing friends and I still regard him as the best, white electric blues guitar player on the planet. He’s also a really good percussionist and is adept on African and Indian hand drums. He opened my mind to a lot of other music.

But to see Chris in this psychedelic blues trio was eye-opening. It was like "Who is this guy?"

I’d never seen anybody play guitar like this guy before and he’s playing better than ever now!

It’s a shame nobody’s ever heard of him outside of Australia and it’s only since he ended up working with people outside of South Australia that the rest of the country has even heard of him.

RM: I assume he still concentrates on his home area with no real urge to go beyond?

GA: I don’t think it’s an urge issue. Australia’s a pretty big place and in those days we didn’t really think of a global situation.

So, anyway, Chris Finnen was opening for a local band called Mickey Finn, ex- Fraternity who Bon Scott fronted before he joined AC/DC. When Bon left Jimmy Barnes took his place...

RM: Oh, he’s not a bad singer and fairly well known (laughs).

GA: Jimmy’s brother Swanee, who I briefly played with in the 80’s, was the drummer in that band. He’s a great singer, too.

So this is the history of Mickey Finn, this fabulous, hard rockin’ R&B AC/DC type boogie ‘n’ blues band with a mad front man Uncle John Ayers who used to hang upside down from the rafters (laughter) and play really wicked blues harmonica! These were the days of big PA systems and Uncle would climb up on top of the PA and jump off and people would catch him – but he would be blowing his harmonica the entire time!

And if he fell over and hurt himself he wouldn’t have felt it anyway, because he was too anaesthetised (laughs) from whatever he had been taking that day!

RM: Great story. That whole scene and vibe you’ve just described – that wonderful, hard rock energy within a blues format – clearly that was an influence because you carry that through your own music and solo albums…

GA: Oh yeah, yeah, the whole Australian rock and roll thing. These guys had 2 x 100 watt Marshalls each (laughs), they weren’t there with a nice little Fender twin reverb. They meant business.

And their attitude was it’s not playing in a band, it’s war. It was a military procedure on stage – the stage was where you had to carry out this intricate operation. And that was their attitude towards playing.

That’s where I developed my sense of focus for a band. Now everybody wants to play with everybody else – everybody wants to be a bloody session player!

You know, this guy wants to play with that band and this band, then with that bloke over there; bass players want to be in ten bands… and that’s not a team spirit.

If you are in a band you’ve got to have the camaraderie and you’ve got to have the communication and the focus and the goal. That’s the old band spirit.

I was watching Chris Robinson on Youtube last night and he was talking, back in ‘95 or something like that, about exactly that. And I thought to myself that’s why guys like that succeed, because they have a community spirit within their band and nobody can touch that.

John Lennon didn’t go running off with the Rolling Stones to do a few gigs with them. When times were tough, they didn’t go and join other bands; they ate dog food and slept on pool tables, because they believed in what they did.

RM: That’s exactly what it comes down to – belief in the music and having that focus, that drive. It’s still around but it’s not for every band.

There are acts out there that can plug in a replacement, session musician or a tribute singer at the drop of a hi-hat and go out and play what are predominately Greatest Hits sets. And that’s fine, because that’s what sells and that’s what the majority seem to want.

But the camaraderie, the group chemistry, that’s something we don’t see so much of in this reimagined day and age, not when compared to the musical melting pot of the 70’s and that whole creative period.

GA: And in the 60’s, when Ringo got tonsillitis and Jimmy Nicol had to fill in on drums. But it wasn’t the same, you know?

RM: No, absolutely. Thanks for sharing those great stories about your formative years and the blues scene in Australia.

But by the early 90’s you’re telling your own blues stories – in 1993 you released your debut album Feel the Heat and three years later Beg, Borrow and Steel. There’s a lovely contrast between the two albums – the debut is modern blues rock while Beg, Borrow and Steel is acoustic based…

GA: Well what happened was – and I haven’t told anyone this story – I wanted to do an acoustic album, because I was leaving Australia and I needed something I could go out with and be play by myself and do solo gigs. But I didn’t have any money, so I traded a piece of studio gear for a day’s studio time.

They knew that I had it and they always wanted to buy it off me, so I said I was going to sell it.

It was worth five hundred dollars and the studio was five hundred dollars a day. So I said "do you mind if I do a day in your studio and I give you the Roland Dimension D?" and they said "no, that’s great."

But what they didn’t stipulate was how long a studio day went on for (laughter).

These days in a studio a day is eight or ten hours, but we didn’t exactly agree on how long a day was (laughs), so I went in at ten o’clock in the morning to record Beg, Borrow and Steel and I left the studio at ten o’clock the next morning!

A few days earlier I’d thought it would be nice to have a few friends play on this, so I just rang around and said "Look, I’m doing a session the day after tomorrow, do you want to come down the studio and play?"

And they all said ok, so it became a jam – the whole thing was a jam session.

The keyboard player, Mick O’Conner, had a gig up the road from the studio so he could come in just before sound check and he could come in after the gig, at one in the morning! (laughs).

So I went in at ten o’clock in the morning and put down most of the tracks I had to play on, by myself, then the other guys dribbled in during the day.

I was pretty tired (laughs), but the whole album was mixed at ten o’clock that next morning. I did an album in 24 hours, mixed it and came out with a two-track mix ready to master!

GA: And the reason I did this whole thing was because my friend Rooster McBlurter ran a club called Muddy Waters café in Melbourne, where I was living at the time. I used to play there every week, or every couple of weeks. He said "You need a solo album." And I thought "that’s a good idea!"

This was on the Thursday – on the Monday I was in the studio and by the next Thursday I gave him the finished, mastered album (laughs).

He wrote a review that said something like "this guy doesn’t stuff around. I said to him last week he should do an album and a couple of days later he comes back and gives it to me!"

RM: A great example of ‘be careful what you wish for’ (laughs).

GA: Yeah, exactly! So it was through necessity and lack of money that I did that album. It’s done me quite well over the years, considering it cost me nothing to make!

RM: Well I have to tell you Beg, Borrow and Steel is probably my favourite release of yours, primarily because of its rough honesty and loose, acoustic vibe.

And hearing the story behind it just makes me warm to it even more.

GA: Thank you. After I caught up with my jet lag (laughs) from staying up all night making the record – the very next day actually – I went to a friend of mine, Gareth, who has a guitar store in South Melbourne.

He said to me "you need someone to design a really good cover" and I said "Yeah, I know!"

But this was before digital photography, you had to have plates made up and it was all very expensive – I did all the artwork on Radiogram myself, even the photography, and that cut a lot of costs I can tell you!

Anyway, Gareth told me he had a friend who was a graphic designer and he serviced major labels such as CBS Records and he should design my album cover. I was on a strict budget, selling stuff so I could afford to come to England to live.

But he showed me his portfolio of everything he had done for magazines and record companies and he said "I’ll do the whole thing for two hundred bucks and that includes developing the photos, coming out to do the shoot, wherever you want to go, and the album cover." Two hundred dollars. That’s only eighty quid!

I said "I don’t wanna take advantage of you" but he said he worked for the majors and he’d just get someone else to pay for it – "Just give me a couple of hundred bucks and I can buy some beer" (laughter).

So we did it that day but I still didn’t know what I was going to call the album at that point.

But as I was driving home I just had this flash to call it Beg, Borrow and Steel. I begged and borrowed from everyone and Steel because it was my National steel guitar that I recorded most of the album with and it would be a little in-joke about how I got the record together. I’ve never told anyone that story before, either!

RM: Well from my point of view it’s great to hear all this background because there is something about that album that really works for me. I take your point about being able to do it a lot better now but it just has that vibe – and some great songs.

GA: Well, they’re very basic songs and recording. You can come out with something pretty good in a short space of time if you put your mind to it.

RM: In time you moved on from the acoustic Beg, Borrow and Steel to the electric, up-tempo Fang It! and Prohibition.

For those that don’t know Fang It! featured Gerry McAvoy and Brendan O’Neil, the late and great Rory Gallagher’s classic and longest serving rhythm section; on Prohibition you had the Sensational Alex Harvey Band boys Chris Glenn and Ted McKenna…

GA: Meeting those guys was great and there are stories to everything that happened with them, too!

When I left Australia to come to England I gave myself five weeks to get across America. I booked a flight to L.A. and then a flight from New York to London and I’ve been here since then.

I just thought I’d have an adventure for five weeks. I had no plan or no idea where I was going to stay – I ended up staying at peoples’ houses that I met along the way and only had to stay in two hotels the entire time. Just two nights in two different hotels through the entire five weeks, which was pretty amazing!

I was in San Francisco, sitting in the car I had rented, about to go back to where I was staying and then I thought "there’s a jam night in Berkeley, shall I go to that, or shall I just forget it?" Because I’d had a bit of a bummer of a night and this was about eleven o’clock so I thought it was probably going to be over by then.

So I flipped a coin and ended up going to the jam night. And one guy, who was talking to me at the end of the night, was Etta James’ guitarist, Bobby Murray.

He liked my playing and he gave me a card for his record company in New York and he said "these guys might like your stuff, tell them I sent you."

So I rang them up the next day, sent them a couple of CDs and that ended up getting me a gig in New York the day before I left to come to England.

I went in to their office in New York and they gave me some contacts in England – one was Gerry McAvoy and another was Pete Brown, who collaborated with Jack Bruce and wrote Sunshine of Your Love and many other tracks for Cream.

Pete and I are still friends, in fact I spoke to him a few days ago and we’re going to catch up this week I think.

So I rang Gerry up and he said "yeah, come out to a gig and I’ll meet you" and I went over, met him and gave him a CD. Gerry gave me some supports with the band he was in, Nine Below Zero, which was great.

Gerry was also reforming his Rory Gallagher memorial Band of Friends and he asked me if I’d consider fronting it.

I was basically replacing Brian Robertson and Robbie McIntosh. They’d performed a one-off show somewhere in Europe and Gerry wanted to carry it on.

This was an honour to be considered for such a role and Rory’s brother Donal told me he liked the fact that I wasn’t cloning Rory but gave it my own interpretation. That meant a lot to me.

My record label at the time thought that it would be a natural thing to use Gerry McAvoy and Brendan O’Neill as the rhythm section on ‘Fang It!, my next album. Dennis Greaves produced it, so all the Nine Below boys were involved.

In actual fact Fang It! was never really finished, because I laid the guitar tracks down as guides with my amps covered over with carpet to reduce bleed into the drum mics and I didn’t get the best guitar sound or performance.

They ran out of time and the record company ran out of money, so they had to leave it with the original guitar tracks on and just work with them.

They were paying for the record, but from that day I vowed I would always be in control, because I don’t want that situation ever happening again. If I can’t afford to finish it I won’t finish it.

RM: That’s unfortunate and it must leave a bad taste in the mouth; you must know as a musician when something is unfinished or is akin to the painting that needs that finishing touch. It must always be in the back of your mind that it could have been that bit better…

GA: Exactly. I had no control over it, I don’t own the album and I don’t own the rights. And since then I’ve pretty much covered it myself.

When I went on to do Prohibition with Chris Glen and Ted McKenna in Ayr in Scotland, it was a home studio guy that they’d lined up. I get there with three amplifiers and fifteen guitars, and the sound engineer goes "oh, aren’t you going to DI [Direct Input] the guitars? I didn’t know you were going to bring amplifiers."

I said "we’re doing this live, obviously, it’s a rock and roll album!" (laughs).

The studio wasn’t prepared and didn’t have enough microphones so I had to go out that day and buy some.

I sat around and watched what he did and thought "I can do that," so since then I’ve tracked my own albums. I know the sounds I want to get and can visualise the finished product so why have someone else get in the way unless they bring something to the table that I hadn’t thought of?

RM: Having total control is clearly the way to go – if you can do it – but it’s not every musician that has production or mixing or engineering skills…

GA: I didn’t either! I’ve made a few friends and I’ve hung around a few studios watching people do stuff.

So when Dave Small and I went to record Two-Man Blues Army over a few days in 2009, I thought "ok, I can do all this stuff, we just need a room to record!"

Dave was playing in a band with Robert Plant’s son – Dave and he are about the same age – and Robert came out to the room we had and said "this room is just like a room where Jimmy Page and I used to record. If I were you I’d just nail some carpet up to that wall" (laughter). So that’s what we did!

It was Dave’s parent’s office, in a workshop in Kidderminster in Worcestershire, and we took over that room. They had to use their van as an office for a week while we recorded the record (laughter), which was kinda fun. We were drilling holes in the walls and everything to feed microphone cables through – it wasn’t sound-proofed or anything but it doesn’t matter. A good room, microphone placement and ears are all you need.

So I had all the gear set up and my mastering engineer, David Mitson, came down and helped get us started. He showed me basically how to get sounds down in a digital audio workstation. He told me "as long as you’re not clipping anything and the sounds are good, then you’re halfway there!"

And then I spent six months going to four studios to try and get them to mix it, but every time I came away I’d go "I don’t like the sound of that" (laughter).

So I just took the raw files and sat at my mobile studio in my van with a pair of headphones and monitors – so I could crank it up – and stayed up until six o’clock in the morning, just about every day, learning how to mix my own album (laughs). And I didn’t know how to use compressors so I was going to every, single, drum beat that might have been a bit too loud on a track and learned how to use the automation of bringing down just that one beat – whether that was the snare drum, or the bass drum, or whatever (laughs).

RM: It sounds like you were literally mixing beat by beat…

GA: Every beat, through a fifty minute album; that’s a lot of work (laughs).

RM: So from twenty-four hours of Beg, Borrow and Steel to six months of learning the digital trade.

You’ve come a long way (laughs)…